httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OY4HdGJcJVo

The Reduced Shakespeare Company’s very funny and completely irrelevant biography of Shakespeare

Today is the anniversary of both Shakespeare‘s birth (traditionally ascribed to this date) and his death: 1564-1616. If we decide to observe this anniversary here every year, we’ve got lots to work with because the new Collected Works volume of Frye on Shakespeare is now out.

Frye produced more essays and books on Shakespeare than on any other writer, Blake included. The reasons don’t need to be guessed at. Shakespeare’s is a comprehensive literary imagination, and the four traditional dramatic genres — comedy, tragedy, history, and romance — are (if we take the history plays to be a form of irony-satire) expressions of the four mythoi laid out in Anatomy. The two were made for each other.

Now that we seem to be outgrowing the cramped restrictions of the literary criticism of the last thirty years, it’s easier to talk openly again about an imagination so vast that it is difficult to conceive of any boundary to it. Shakespeare’s global appeal is perhaps the best evidence there is of imaginative constants common to all people and all cultures — a universality recognizable as shared human desires and expectations whose imaginative dimension is always available to be explored. Shakespeare’s articulation of them as archetypal concerns is, of course, also a matter of poetry so fully realized that it cannot be entirely lost in translation. His wide appeal seems to be that he not only brings out the best in the English language, but also the best in any language that makes his work part of its own.

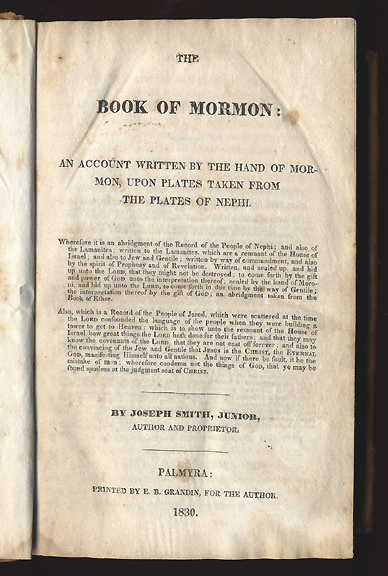

We can begin just about anywhere when it comes to Frye on Shakespeare. It’s always easy, for example, to be drawn to the way he consistently pushes aside our reflexive instincts to engage in biographical fallacy, especially when confronted with genius this expansive. It’s not that Shakespeare doesn’t have a biography that might in some way on some occasions be relevant to the work. It’s that Shakespeare’s literary power far exceeds any biographical consideration. The reductive nature of much Shakespearean critical biography ends up as an embarrassment. As Frye says, when a literary critic takes on Shakespeare, it is the critic and not Shakespeare who is being judged. His unique contribution to Shakespeare scholarship is crediting the independent authority that the literary work itself always possesses, even if that authority is only imperfectly understood. The single biographical detail that gives me a thrill is the coincidence of a life beginning and ending on the same date. It means nothing as a matter of historical fact, but it does suggest that when those arbitrary dates are superstitiously aligned, our notions of life and death may cancel one another out, leaving behind an imaginative perspective that encompasses both. And that is something that is always relevant to Shakespeare.

So let’s start this year with this observation from “Shakespeare and the Modern World”:

Human nature being what it is, a great deal of writing on Shakespeare has consisted of efforts to peek around the personal barrier. I am not speaking of the cranks who have tried to prove that he was somebody else, although the number and vociferousness of them show how irritated people get when they can’t attach a body of poetry to a personal body. I am speaking of serious people who have ransacked the plays for clues to Shakespeare’s moods when he wrote them, and then tried to string the moods together into a biography. In the sonnets, Wordsworth said in a moment of misguided enthusiasm, Shakespeare unlocked his heart; so hundreds of people have read the sonnets for no other purpose than to try to find out who W.H. and the youth and the dark lady and the rival poet were. One scholar, Caroline Spurgeon, studied the imagery of the plays in search of unconsciously dropped clues to the writer’s personality. What emerged was a dismally amiable mediocrity whose favorite game was probably bowls. It is a pitiful haul that scholars have salvaged from their research: a will, a few addresses, a baptismal certificate, and some financial transactions that suggest only a commonplace middle-class snob. (CW 28, 231)