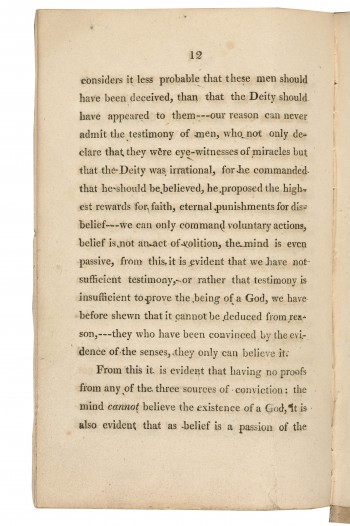

A page from Shelley’s pamphlet

Percy Bysshe Shelley was expelled from Oxford for atheism two hundred years ago today after publishing his pamphlet, The Necessity of Atheism.

Frye discusses with David Cayley Shelley’s “atheistic” cosmology compared to Blake’s Biblically-based one:

Cayley: How does Blake relate to the Romantic movement?

Frye: I think Blake wraps up the whole Romantic movement inside himself, although nobody else knew it. You can find a good deal of the upside-down universe in all of the other Romantics, most completely, I think, in Shelley, where a poem like Prometheus Unbound everything that’s “up there,” namely Jupiter, is tyrannical, and everything that’s down in caves is liberating.

Cayley: But Shelley takes this in a more atheistical direction than Blake does.

Frye: Shelley doesn’t derive primarily from the Biblical tradition in the way that Blake does. Blake is always thinking in terms of the Biblical revolutions, the Exodus in the Old Testament and the Resurrection in the New Testament.

Cayley: In other words, Blake has a given structure of imagery from the Bible that he works with, and that distinguishes him from the other Romantics.

Frye: It certainly distinguishes his emphasis from Shelley. (CW 24, 959)