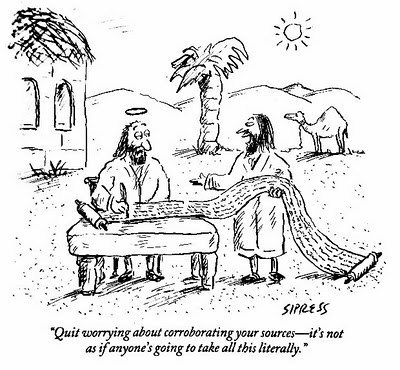

Both Frye and Bloom have written some interesting and even wise things about specific Biblical texts, and I hope my course does them justice, but both of them have a “system” for reading literature into which Biblical texts are fitted, sometimes in Procrustes’ manner, by main force, and both of them have the habit, common with us professors, of pushing their commentary beyond their specific knowledge base of history and language.

The Book of J is an embarrassment even to those who find Bloom’s other books admirable because he grounds his commentary on a grotesque translation by David Rosenberg rather than on a more reliable English version (the RSV would have been far better) or on the Hebrew original, which he evidently cannot read since he makes such elementary mistakes. His theory of the authorship of the J narratives says more about Bloom himself and his quarrel with the feminists than about the narratives. But I find his analysis of Yahweh as an uncanny character in some of the J stories genuinely interesting.

Whenever Frye alludes to the Hebrew original he is accurate more often than not (his batting average is way ahead of Harold Bloom’s); his mistranslation of hevel as “fog,” for which Robert Alter skewered him is not a typical mistake.

And there is nothing wrong with his cyclical vision of Biblical history except that any narrative that includes a number of periods of independence and prosperity alternating with periods of oppression and want can be made into a set of cycles. (Frye wasn’t the only one to employ “circular” reasoning like this: a different version of Frye’s cycles on p. 171 of The Great Code appears in “The Sacred Center,” an early article by the great Biblical scholar Michael Fishbane. And sports writers do it all the time, of course, with their cycles of “winning streaks” and “losing streaks.”)

And I guess I can’t quarrel with the way everything in the Bible seems to be squeezed into the categories of Anatomy of Criticism, since many of those categories sprang in the first place from Frye’s readings of the Bible.

I expect my main problem with Frye is the way he free-associates (or should I say frye-associates) in ways that I simply cannot follow (e.g., Joseph’s “coat of many colors” suggests to Frye that Joseph is a fertility god). Maybe I’m dim but I don’t see the connection, and whether it would disappear if we were to translate ketonet pasim correctly.

In Myth II of The Great Code, Frye gives us a moving analysis of the book of Job, much of the time, but we get sentences like “The reintegration of the human community is followed by the transfiguration of nature, in its humanized pastoral form. One of Job’s beautiful new daughters has a name meaning a box of eye shadow.”

This is not just distracting. The narratives, which are often intricately shaped at the level of incident and the level of language, simply disappear into this network of frye-associations. And Biblical characters, some of whom, like Jacob and David, we can follow from youth through maturity to old age and death, disappear into their other avatars.

Similarly, Frye knows that “ha-satan” in OT narratives like Numbers 22 and Job 1-2 is a servant of the LORD and not His demonic adversary as in Mark 1:13 and elsewhere in the NT, but Frye can’t help conflating them, even though he knows better, and even though it totally distorts the Hebrew narratives.

Anyway, I do want to back-pedal a little from my “whipping boys” quip in the syllabus. Whenever I teach theory, and not just in my Biblical Narratology course, everyone is a hero and everyone is a whipping boy, as we try to see both the powers and the limitations of the method of each critic my students and I read together. It isn’t just Bloom and Frye, we also see Robert Alter and Meir Sternberg and Mieke Bal and Jan Fokkelman in the same critical light, as having questions they can answer and questions they can’t even ask. And I wouldn’t include Bloom and Frye in my syllabus if I didn’t think they had interesting methods and interesting things to say using them.