Blake’s “To Annihilate the Self-hood of Deceit,” 1804-1808

I’ve posted this before, but it is worth looking at again. Frye in Fearful Symmetry takes on the money economy from a prophetic perspective:

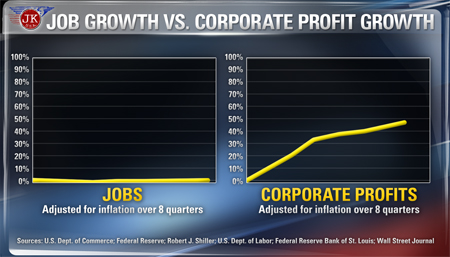

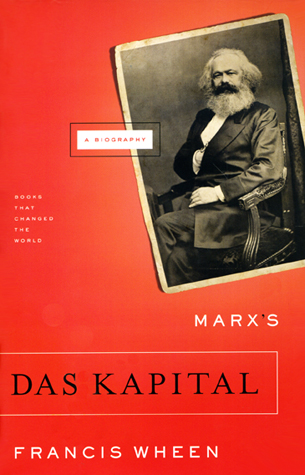

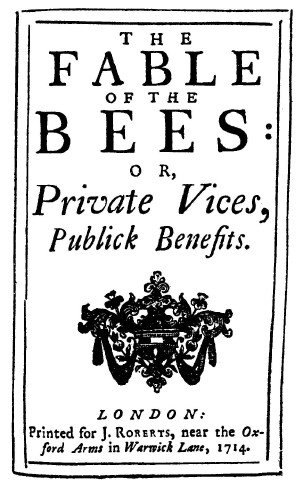

Money to Blake is the cement or cohesive principle of fallen society, and as society consists of tyrants exploiting victims, money can only exist in the two forms of riches and poverty; too much for a few and not enough for the rest. La proprieté, c’est le vol, may be a good epigram, but it is no better than Blake’s definition of money as “the life’s blood of Poor Families,” or his remark that “God made man happy & Rich, but the Subtil made the innocent, Poor.” A money economy is a continuous partial murder of the victim, as poverty keeps many imaginative needs out of reach. Money for those who have it, on the other hand, can belong only to the Selfhood, as it assumes the possibility of happiness through possession, which we have seen is impossible, and hence of being passively or externally stimulated into imagination. An equal distribution, even if practicable, would therefore not affect its status as the root of a evil. Corresponding to the consensus of mediocrities assumed by law and Lockean philosophy, money assumes a dead level of “necessities” (notice the word) as its basis. Art on this theory is high up among the nonessentials; pleasure, in society, tends to collapse very quickly into luxury and affection. (CW 14, 82)