Responding to Joe Adamson’s comment

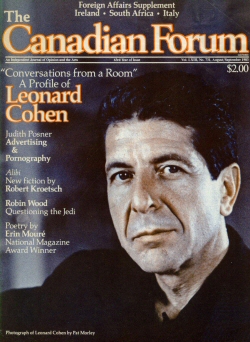

Yes, Joe, Frye’s social and political views come through clearly in the editorials he dashed off when he was editor of the Canadian Forum. Somebody ought to write the story of his involvement with the Forum, the politics of which pretty much followed those of his predecessor as editor, George Grube, which is to say that they leaned quite left of center. Frye had a great respect for Grube, though Grube was more inclined to have the Forum be a mouthpiece for CCF politics. Frye told an interviewer that at the Forum he “always established a distinction between politics and public affairs. That was a distinction which Grube never accepted. He just didn’t believe that there was such a thing as a discussion of public affairs aside from a political approach. But I think the distinction is there, and I felt that the Forum ought to be what it was called on its masthead after I came in, that is, an independent journal of public opinion, and it should be as free to criticize the CCF as any other group of writers.”

Frye was not opposed to all anarchism, just the violent and terroristic variety––of the kind he witnessed when he was at Berkeley in 1968. Anarchism of the pastoral variety, as in, say, the Amsterdam provos, or the anarchism of Kropotkin’s mutual aid, he could affirm.

“The radicalism of today,” Frye wrote in 1968, “is closer to nineteenth-century anarchism than to the Communism of Stalin’s era. Like the anarchists, contemporary radicals think in terms of direct action, or confrontation; and their organizing metaphor is not so much takeover as transformation or metamorphosis. Nineteenth-century anarchists showed a curious polarizing in temperament between the extremes of gentleness and of ferocity: there were the anarchists of ‘mutual aid,’ and the terrorist anarchists of bombs and assassinations. The essential dynamic of contemporary radicalism is non-violent, and its revolutionary tactics seem to descend from Gandhi rather than Lenin. When contemporary protest movements commit themselves to violence, they show some connection with the fascism of a generation ago, a similarity which confuses many people of my generation, whose ‘left-wing’ and ‘right-wing’ signposts point in different directions. They feel turned around in a world where not only the Soviet Union but trade unions have become right-wing, and where many left-wing movements utter slogans that sound very close to racism” (“The Ethics of Change”).

I wonder if the records of the Forum during the 1940s and 1950s have been preserved.

Robert Fulford’s 2001 article on the death of the Forum here.