Reubens, Venus and Adonis, c. 1635

Responding to Jonathan Allan.

“Virginity means a transcending of sex”––“Third Book” Notebooks

I suspect that Frye associates females with virginity because that is the typical association he found in the tradition of literature, sacred and secular. But he clearly recognized the category of the male virgin. In Words with Power he writes,

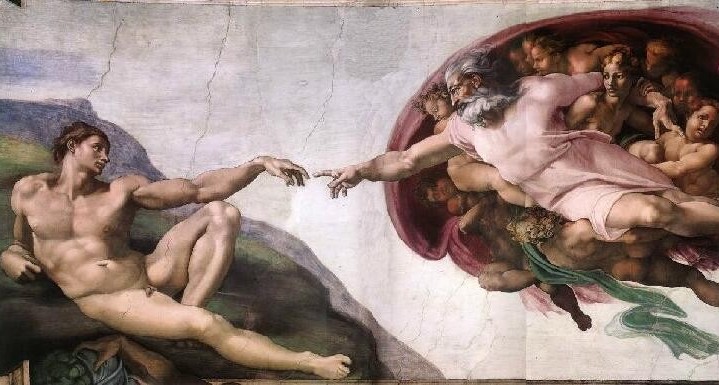

The original adam, alone in his garden, was involuntarily virginal, and illustrates the theme of the virgin who has a peculiarly intimate relationship to an idealized natural environment. The term virgin is usually associated with females, but long before Genesis we have the pathetic story of Enkidu in the Gilgamesh epic, the wild man of the woods made by the gods to subdue Gilgamesh, but so feared by human society that they send a whore to seduce him. After she completes her assignment the link between Enkidu and the animals who once responded to his call was snapped forever.

The figure of Orpheus in Greece, if not strictly virginal, also has a magically close affinity with nature: he is a musician, and music symbolizes the harmony that holds heaven and earth in union on the paradisal level of existence. Female virgins, again, have been credited for centuries with magical powers over nature, including the taming of wild beasts, the attracting of unicorns, and an uncanny knowledge of herbs.

In his notes on Achilles Tatius, The Adventures of Leucippe and Clitophon, Frye observes that when the

hero is making row about sacrilege in temple he says he’s a free man and a citizen of no mean city (ouk aemou poleos polites), which is quoted from Acts 21:39. Maybe Achilles Tacitus was a bishop after all: his bishop, anyway, if the translation is right, is a most urbane character, said to be familiar with Aristophanes, whose speech in court is full of double entendres about his opponent’s character (Thersander). Note the continuity of Paul’s wanderings around the Mediterranean and later romance. It must mean something that the heroine’s virginity is preserved only by accident and the hero’s isn’t at all.

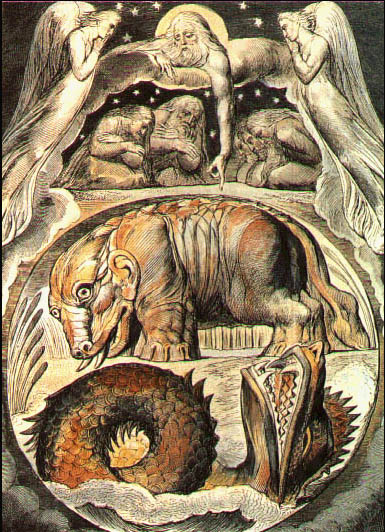

In Notebook 50, par. 9, Frye writes about the passage in Revelation 14:4––“the business about those not defiled with women.” Later in the same notebook (par. 242) he says, “The male virgins in Revelation [14:4] (I probably have this) are the antitype of the fucking sons of God in Genesis 6.” Then again (par. 453), “It’s bloody confusing to read in Revelation that the redeemed are all male virgins, never ‘defiled’ with women [14:4]. [See Words with Power, 127, 275.] Not that anyone ever took it––well––literally: cf. the 14th c. Pearl. [The Pearl-poet did take the Revelation account literally. See Pearl, ll. 865 ff., where the poet takes pains to insist that the account of the male virgins in Revelation is true.] Its demonic parody, as I’ve said [par. 242], is Genesis 6:1-4: the Rev. [Revelation] bunch are sons of God who stay where they are, & don’t go “whoring” after lower states of being.”

In Words with Power Frye refers approvingly to Meister Eckhart telling “his congregation that each of them was a virgin mother charged with the responsibility of bringing the Word to birth; but then Eckhart did understand the language of proclamation that grows out of myth, and its invariable connection with the present tense.”

The notion of male virginity is implicit in this passage from Notebook 3 (par. 67):

Virginity is of course a Selfhood symbol, and the surrender of virginity in marriage is part of the losing one’s life to gain it pattern. By entrusting their virginities to one another, husband & wife recover their individualities, & advance from the purely generic physical relation to the purely human one of companionship. Possessiveness & jealousy are thus the perversions or analogies of what really happens in marriage. Blake would say that the hymen was the home of the Amalekites.

And then this, from “The Third Book” Notebooks (Notebook 12, par. 394):

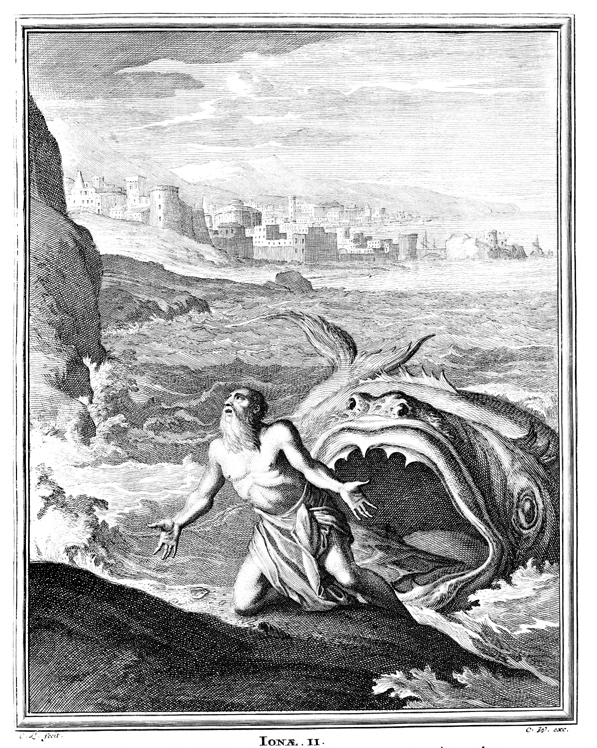

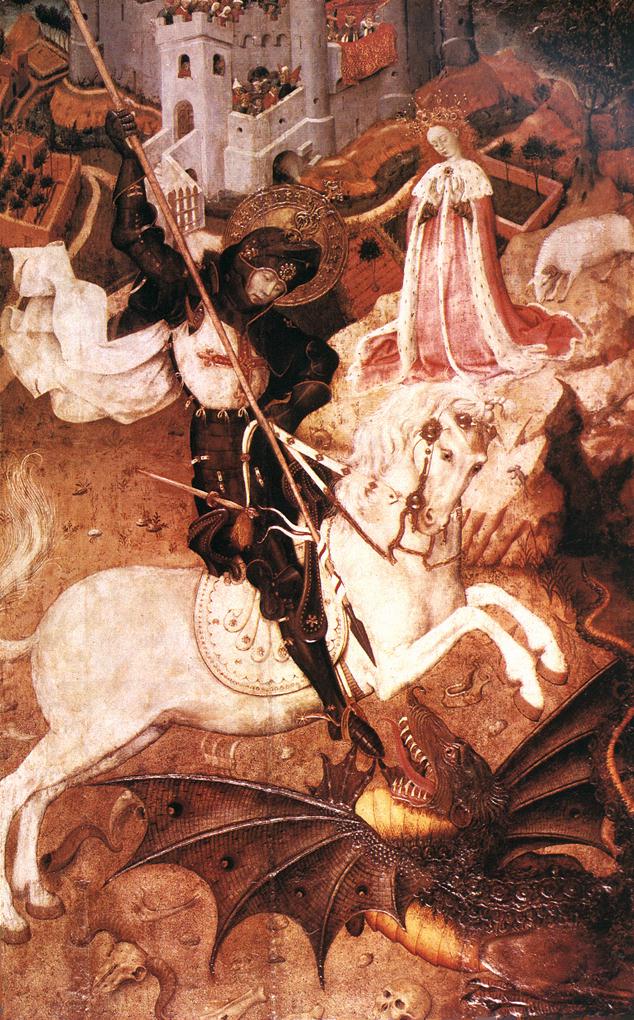

Pound’s remark, a far more incisive one than Nietzsche’s, about the difference between those who thought fucking was good for the crops & those who thought it was bad for them, defines the contrast between the shy virginal Adonis, the women lamenting his virginity like Jephtha’s virginal daughter, Attis with his castrating priests, Jesus with his “touch me not” & his homosexual refinement—chaste, anyway—& his elusive ascension, are all in the upper sphere of the purified soul. [Pound’s remark: ““The opposing systems of European morality go back to the opposed temperaments of those who thought copulation was good for the crops, and the opposed faction who thought it was bad for the crops (the scarcity economists of pre-history)” (Ezra Pound, Make It New [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1935)], 17).]

In short, I think the notion that “virginity [is] uniquely concerned with the female subject” in Frye needs to be qualified by considering his occasional remarks about male virginity.