Lecture 2. October 7, 1947

The writers of the Gospels were writing about Jesus, but they are not writing a biography. The events are there because they fit the pattern of what the writer was trying to present. The life of Jesus is the drama of spiritual Israel. When we study the Bible we see that the Book of Isaiah are fragments pasted together and that a lot of editing has been done. We cannot accept the Bible as the work of one man, but we can look at it as a complete book, a unity. It has editorial unity, and this is true of the whole Bible.

The first part of the Bible is arranged by people influenced by the Prophets. The opening books are later, written by men impressed by the earliest Prophets, such as Amos, in the 8th century. The Exile took place around 586 B.C. Before that, there were attempts to reform the early religion, such as taking old traditional laws and reforming religion according to the teaching of the Prophets. Then you’d have the Law and the Prophets.

The Book of Laws is an attempt to reform religion according to the spirit of the Prophets that there is no God but our God. The Prophets taught a historical dialectic and Genesis to Kings is written in this light. The sanctity of the Law and the truth of the prophetic interpretation is their dialectic of history. The Torah is the Law, the first five books. The former prophets were historians, the latter were like Isaiah.

The Torah is the Jewish kernel of their Bible, and the Christian Gospels are the commentary on the Law. The Law in the first five books has an elaborate ritual and ceremonial code, as well as the moral duties of the law and punishments, as in the Ten Commandments.

In a primitive society there is little distinction between moral and ceremonial law. The framework of the narrative tells the story of the Hebrew people from the Creation to the entry into Canaan. The kernel is the descent into Egypt and the deliverance into the Promised Land. The narrative focuses on a different level: Abraham is the Hebrew tribe; Jacob is Israel. Here we are dealing on a plane in which the nation is conceived as a single person. The story of Jacob’s descent into Egypt is the story of the people. It is based on historical reminiscence, but we don’t know what. However, we needn’t worry about it as history, but look at it as a single pattern.

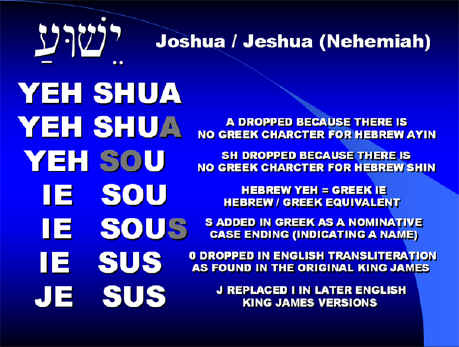

The Israelites go down into bondage, a kingdom of darkness, another fall, of Israel. The plague of darkness is the most deeply symbolic. The dream of the Promised Land is the Garden from which man fell. The leader, Moses (Son), leads them through the wilderness to the boundary of the Promised Land. But Moses does not conquer it; that is reserved for Joshua, whose name means Jesus. Israel was guided through the wilderness of the dead world by the power of the Law and a man names Jesus began the assault on the Promised Land.

The Exodus is the central story of Israel. Here you get Joseph, one of the twelve brothers who goes to Egypt. There is a cruel king, a massacre of the firstborn. Then comes deliverance by Moses (son), the Exodus, the crossing of the water, the Red Sea, the forty years in the wilderness. The New Testament parallel is Jesus, Egypt, a cruel king, leaves Egypt, twelve followers, baptism in Jordan, forty days in the wilderness. Moses is the law, so he can’t enter the Promised Land, but Joshua (Jesus) does. The Annunciation in the New Testament is the annunciation that the assault on the Promised Land has begun. Egypt is the fallen world, the Promised Land is the Kingdom of God.

The symbol and allegory of the Old Testament become reality in the New Testament.

Old Testament New Testament

Manna Bread of life

Water out of the rock Water of life

Serpent of brass Crucifixion

Promised Land Resurrection

(Joshua) (Jesus)

The Gospels are indifferent to proof, historical proof. The people who saw Jesus’ life are a mixed bunch. They are not concerned with how He came but with how He comes. This is what always happens.