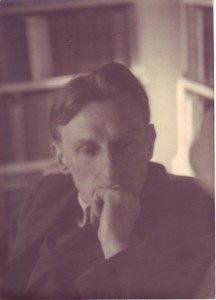

1. Frye in Italy.

The most extensive connection that Frye had with a foreign country was with Italy, a country he visited on seven occasions. In March of 1937, during his first year at Merton College, he spent time between terms touring Italy with Mike Joseph, a fellow student, visiting Genoa, Pisa, Siena, Orvieto, Rome (where they meet another fellow student, Rodney Baine, and two students from Exeter College), Perugia, Arezzo, Florence, San Gimignano, Assisi, Ravenna, Venice, Verona, Mantua, and Milan.

Two years later, after Frye has finished his Oxford exams, he and Helen took a hurried trip to the continent, leaving London for Paris in late July and meeting Mike Joseph in Florence for a two‑week trip through northern Italy, where they found it difficult to escape the presence of Mussolini:

Some of our friends have objected to our taking a holiday in a Fascist country, feeling that we ought to spend our handful of vacation money in those noble, generous, brave‑spirited, free republics, Great Britain and France. Well, perhaps. Certainly at Sienna, where we had an air‑raid practice and a blackout, we began to get restive at being in an officially hostile country with the papers all hermetically sealed against news. “La politica non è serena,” as our landlady said. But surely away up on this mountain, breathing this free mountain air (one of the voices of liberty, according to Wordsworth, who ought to have known), we can forget about Mussolini for a few hours.

When we get there we find, however, that the town has been made into a “national monument” and Mussolini’s plug‑ugly sourpuss is plastered all over it. His epigrams, too. For every conspicuous piece of white wall in Italy is covered with mottoes in black letters from his speeches and obiter dicta—the successor to the obsolete art of fresco‑painting. One of them says, with disarming simplicity, “Mussolini is always right.” “The olive tree has gentle and soft leaves, but its wood is harsh and rough,” says another more cryptically. “War is to man what maternity is to woman,” says a third. “The best way to preserve peace is to prepare for war,” says a fourth, and it looks just as silly in Italian as it does in English. Another one of the few not of Mussolini’s authorship reads: “Duce! We await your orders.” Up here they present us with “We shoot straight.”

One of these, “The nation should be as strong as the army and the army as strong as the nation,” reminds us how Italy is taxed to the back teeth for her army and how oddly all this gathering of pearls from swine contrasts with the miserable poverty of the town, a poverty as patient and humble as that poor old donkey. But is it so odd? Peasant feeds soldier and soldier kicks peasant—that was the Roman arrangement, so why not now, when the grandeur of Rome is revived and the national emblem once more is a whip? (“Two Italian Sketches. 1939,” Acta Victoriana 67 [October 1942]: 12–14, 23; rpt. in Northrop Frye on Modern Culture, 188–93).