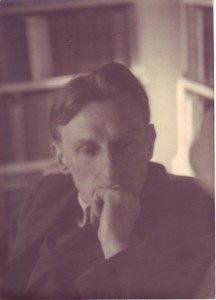

Edmund Blunden in 1938

The relationship between Frye and his Oxford tutor is, like most human relations, complex. Frye’s attitudes toward Blunden emerge during the course of his correspondence with Helen Kemp (Frye). Blunden’s view of Frye is more difficult to untangle. Other than Frye’s statements about Blunden in the Frye‑Kemp letters, I think Frye makes only five references to his tutor. In a 1942 diary entry, he mentions Blunden in passing: “I’d like to write an article on Everyman prudery sometime. Geoffrey of Monmouth; the translator’s smug sneer on p. 248. Malory, according to Blunden” (Diaries 33). The meaning here is uncertain, but perhaps Frye is remembering a remark of Blunden’s that the Everyman edition of Malory’s Arthur had been bowlerdized.” There’s another passing reference in Frye’s foreword to Robin Harris’s English Studies at Toronto. In his 1952 diary he remarks that Douglas LePan had visited Blunden in Tokyo (504). The fourth reference comes in a review of C. Day Lewis’s translation of Virgil’s Georgics: Frye writes that the translation has “much in common with the best of the English bucolic school: with Shanks, Blunden, Edward Thomas, and Victoria Sackville-West’s The Land” (Poetry: A Magazine of Verse 71 [March 1948]: 337-8). Then in a review of Robert Graves’s Collected Poems Frye writes that Graves is closer in technique to Blunden than to Eliot (Hudson Review 9 [Summer 1956]: 298).

These remarks are inconsequential for understanding the Frye‑Blunden relationship. In an interview with Valerie Schatzker Frye reports that Blunden “was a rather shy, diffident man.” At least they had those traits in common. Then Frye adds, signaling an enormous difference, “for some bloody reason, which I’ve never figured out, he was pro‑Nazi. I didn’t know who to blame for that.” In a letter to Helen (28 May 1937) Frye wrote that “Blunden came back from Germany full of enthusiasm for the Nazis.” Blunden was in fact accused in 1939 of being a Nazi sympathizer. Here’s the way his politics is presented on the Edmund Blunden website, established by his family:

In April 1940 Edmund wrote to the Times to deplore plans to bomb German cities, fearing for the inevitable killing and wounding of civilians. As a result, Annie’s [Annie was the German wife of Blunden’s brother] home in Tonbridge was raided by the police who took all [his wife] Sylva’s letters to Edmund, and returned to the house to go through all Edmund’s books. Edmund told the Warden of Merton that he had already written to his old Commanding Officer, [Col. Harrison in Undertones of War] to offer his services, and soon found himself in uniform again as an officer in the University’s Officers Training Corps.

Blunden was not interested in politics but was vehemently opposed to war. He refused to be drawn into the politics of pacifism. His refusal to politically engage in the late 1930’s led to him being labelled a Nazi and subsequently, in the 1950s, a communist, following his visit to China, shortly after the end of the Korean war. His belief in the fundamental goodness of the ordinary man and the need to avoid war at all costs, consistently led him to being politically misunderstood, particularly during the tumultuous events of the 1930s. He used his writing, public speaking and visits to Germany in an ambassadorial attempt to influence opinion against any recurrence of the 1914-18 conflagration. This was emphatically not a political voice but one that believed in bringing nations together by talking to each other and building strong human ties. He was convinced that were his battle-weary generation in positions of power, war would naturally be averted. He was devastated when it became clear that lessons from the tragedy of the Great War were being ignored and in many cases trodden upon. (http://www.edmundblunden.org/productservice.php?productserviceid=299)

It would be interesting to see what Barry Webb’s biography of Blunden has to say about this.

To assess Frye’s perception of Blunden we have to turn to his correspondence. After his first encounter with his tutor, Frye wrote to Helen on 11 October 1936, “Blunden seems a very good head and quite prepared to be friendly. Gentle soul on the whole, I should think, but with an unfortunate propensity to assume I know more about the subject than he does.” Then on 20 October he writes, “I’ve worked very hard most of the week, on my first paper for Blunden. It was on Chaucer’s early poems, which are all in the usual symbolic, visionary form of medieval poetry, and as that happens to be the kind of poetry I know how to read, the paper grew and grew as I worked on it—I spent every waking hour of Saturday, Sunday and Monday on it, practically. Blunden said very flattering things about it, but he obviously isn’t very fresh on Chaucer. That’s the weakness of the tutorial system, I think: the tutor has to pretend to know everything when he doesn’t, like a public school teacher. Not that Blunden bothers to pretend much. I think he likes me, and spoke of taking me out to see Blenheim palace. However, he absolutely declines to take the initiative in deciding what papers I am to write. Next week I tackle Troilus and Criseyde, & may do something with Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida too. I should be rather good on the Shakespeare—I just gave that play a careful reading almost exactly a year ago, and it did something to me—seemed to numb something in me, or paralyze a nerve centre somewhere. I’ve never been the same man since.” Blunden, Frye wrote to Pelham Edgar, “listened patiently and wisely to my burblings for a good many tutorial hours” (9 August 1948).

The record of the essays that Frye wrote for Blunden is incomplete, but during the first year he wrote, in addition to the Chaucer essays (the only ones that survived), papers on Wyatt and Fulke Greville, and he appears to have written essays on Sidney and Lyly as well. For his second‑year tutorials (1938-39) he read papers on Crashaw and Herbert, Vaughan, Traherne, Herrick, Marvell, and Cowley, on the Dark Ages, on the character book, on King Lear, on the anatomy, and on the history of the language. After his first year, he wrote to Roy Daniells that “Blunden is so much like God––very inspiring to talk to as long as you do the talking.” And Frye did a great deal of talking. If his estimate of producing 5,000 to 6,000 words per week is accurate, his steady output resulted in about 100,000 words altogether. Frye sent the papers he had written during his first year to Pelham Edgar, who in turn passed them along to Roy Daniells. Neither they nor his second‑year papers have ever turned up.

In December 1936 Frye wrote to Pelham Edgar that Blunden was “quite satisfied” with his work, although Blunden “got very tired” at listening to Frye’s papers (letter to Roy Daniells, June 1937). And in an end‑of-year report to Walter T. Brown, principal of Victoria College, Frye wrote, “I have been working at Oxford I should think fairly well––at least my tutor Mr. Blunden has given me quite good term reports and seems to be interested in me, so I should like very much to be able to complete the course next year.” He reported also that Blunden had promised to introduce him to the eminent Blake scholar, Geoffrey Keynes, which in fact Blunden did. In another end‑of‑year report to Pelham Edgar, Frye said about his Blake manuscript that “Mr. Blunden has high hopes for its publication and suggests Faber & Faber as a first venture. I don’t really think that it will finally not be accepted.” Blunden, who had “considerable hope for publication,” recommended that Frye send half of his manuscript to Faber & Faber.

If Blunden was initially enthusiastic about Frye’s Blake project, by the second year his zeal had been redirected. He saw that Frye had the ability to earn a first in the “schools,” and so he encouraged him to postpone the Blake and concentrate on his exams. Here’s Frye’s account of the matter to Edward W. Wallace, president and chancellor of Victoria University: “When I came to Oxford [for my second year] Blunden was quite determined, for so mild a man, that I should postpone trying to get the Blake published and concentrate on my exams. All his overseas students turned up with seconds and thirds last year, so he’s backing me this year. I think I may say, after deliberate and mature reflection, that I do not care two hoots on a penny whistle whether I get a first or not: yet I worked fairly hard last term. The sort of glib precocity one needs for examinations does not appeal to me much as a goal; but now that I have discovered that I can make a fairly good teacher I have something tangible to work for. I not only have a vocation: I am beginning to find out what the word ‘vocation’ means” (letter of 13 January 1939).

Now, in Frye’s own words, from his letters to Helen from his first year at Oxford (several of these passages are quoted in part in John Ayre’s biography):

After his second tutorial: “The work is going strong—I keep putting a hell of a lot of work into my papers. I have just finished the Troilus and Criseyde thing. I didn’t get into the Shakespeare, as there were 8000 lines of the Chaucer, and I think I worked as hard over it as I ever did over those theological essays that used to bring in such an impressive list of firsts. I think Blunden approves all right, but his main interest is in things like natural imagery of the 19th c type. I can’t write about that intelligently, as I don’t think in those terms, and neither did Chaucer. So what Blunden says is that the paper is a very fine piece of work, that Chaucer was quite a poet, that that picture on the wall he bought for ten pounds at an auction, and the catalogue described it as School of Poussin and dated it around 1710: would I give him an opinion on the date? also the next time I pass St. Aldate’s Church, would I take a look at the font cover there, which has been varnished out of existence, and which looks medieval, but is, he thinks, sixteenth‑century Flemish work done in a medieval tradition, and let him know what I think about it? So I get up and stare solemnly at his bloody picture, and then announce that my opinion on the date of a bastard Poussin is not worth a damn, and that my qualifications for pronouncing on Flemish font covers are exactly nil. Well, no, I let him down easier than that, so that he thinks I know far more about it than I actually do—you know my methods, Watson. I can see where I shall have to marry you and make you live with me at Oxford next year in sheer self‑defence. . . . So far I’ve gone to two lectures, one by Blunden and one by Abercrombie. They’re rather bad, but I may go to some more, as it’s a good way of meeting some of the other people in the course. The method of lecturing is very similar to the sort of thing you described at the Courtauld—an endless niggling over minutiae and in hopeless disproportion to the very general scope of the course” (27 October 1936).

“I’ve got a piano moved in. I ordered a typewriter, but it didn’t come, so I think I’ll let it go—Blunden never asks to see my papers. . . . Blunden improves. He threw flowers at my feet yesterday, I think because my paper was clever, vague and short—Canterbury Tales. Told me I’d made a real contribution to criticism, etc. etc., and then talked about Blake for the rest of the hour” (3 November 1936)

“I had a tutorial again with Blunden last night. Blunden was vague again—obviously doesn’t quite know what to do with me but would like to be helpful. I shall have to be careful with that man. I mentioned Skelton, and referred to a very bad editor of Skelton as a congenital idiot. Blunden was tickled—he had written a very unfavorable review of that very edition, and had received a rather abusive letter from the said editor in consequence. It was the right remark, but I could just as easily have made it about one of his friends. Speaking of wrong remarks, this man Baine made one, I think. Recently Blunden gave a very good lecture on a minor 18th century poet called Young, and had a swell time quoting bad passages from him, quoting jokes on him, and setting his inflated ideas beside his achievements. As we were coming out of the lecture, I said to Baine: ‘There’s no doubt that a bad poet provides better material for a good lecture than a good one.’ This went away down into Baine’s subconsciousness somewhere, and next day he had a tutorial with Blunden, who asked him something about the lectures he was attending. Baine started a long harangue which went definitely to show that most of the lecturing around here was extremely bad, and after complaining lustily for ten minutes, suddenly realized that it was high time to start exempting present company. So, realizing like many a good scholar before him, that the best way of saying exactly the right thing would be to quote me, he said: ‘I enjoyed your lecture on Young very much, but then I suppose it’s easier to lecture on a bad poet than a good one.’” (10 November 1936)

“Blunden last night. Paper on Wyatt: by no means a bad paper, though not very well organized: I didn’t start writing it until ten that morning, and the splutter over addle‑headed critics as aforesaid also interfered. Blunden said he had noticed that all his students who really understood what poetry was about liked Wyatt, which was no doubt a compliment. That man must listen to my papers more carefully than I thought. I was listening to a lecture of his on Chesterton last Wednesday in which I suddenly heard a paraphrase of a passage in the last paper I read him, followed by an application of the general principle it embodied to Chesterton. After the lecture he nodded cheerfully at me and said: ‘I stole from you, but unwillingly: and it was only petty larceny anyhow.’ I’m just going to take what Blake there is over to him: I want the ‘favorable half‑yearly report’ to get to Ottawa before the end of term.” (17 November 1936)

“I have decided not to write a paper for Blunden tonight. I’m going to go in and twist his neck with my bare hands. I’ve scared the shit out of him, in the Burwash phrase, and I’m just beginning to realize it, and to comprehend why he gives me that dying‑duck reproachful stare every time I finish reading a paper to him. He returned the Blake with the remark that it was pretty stiff going for him, as he wasn’t much accustomed to thinking in philosophical terms. I could have told him that there was a little girl in Toronto who could follow it all right, without making any more claims as a philosopher and far less as a student of English literature. So I think I’ll start cooing to him” (30 November 1936)

“I’ve been invited to Blackpool for Christmas, but there’d be no point in my going—I should get to London. Several people have offered to lend me money, including Blunden, but I haven’t taken it—I may regret that later, of course” (11 December 1936).

“I was examined last day of term by all the dons and the warden, the process being known as a donrag. Said donrag lasted ninety seconds, & consisted of a speech by Blunden and a purr from the warden. . . . I don’t think Blunden liked my thesis much—he said something vague about all the sentences being the same length—what I think he really resents is the irrefutable proof that Blake had a brain. I am afraid I shall have to ignore him and just go ahead.” (17 December 1936).

“Blunden was very pleased with my exam and said nice things. I was disgusted with it myself. If I can make that impression when half asleep, more than half sick and execrably prepared, I ought to be all right on Schools. . . . Blunden has asked me to supper this week” (19 January 1937).

“Well, last Tuesday [Elizabeth Fraser] and a wall‑painting restorer named Long and I went to a town near here called Abingdon, where there’s a church with a series of figures on each side of the chancel ceiling. They are kings and prophets alternately, leading up to Christ and the Virgin in the last panel (some of them are out of place), with a tree of Jesse running horizontally underneath them. The Christ is a beautiful Lily Crucifix—his body is in an attitude of crucifixion, but there’s no cross—just a lily plant covering him. Late 14th century. Varnished out of sight, and some disappeared when they took the roof off in 1872 and put it back on again. Well, Blunden hasn’t seen these, although they’re in the next town and he (or his wife) has written a book on church architecture in England. So he’s coming to see them this week, and he’s coming to tea afterwards, and Elizabeth is coming too. ‘He probably hates churches,’ says Elizabeth. Poor Blunden—but if I didn’t bully him somebody else would—he’s always being bullied by somebody. There’s a minor Elizabethan poet named Fulke Greville—a great favorite of Roy’s [Roy Daniells’s] as well as mine, a very intellectual poet and frightfully obscure at times—quite the thing for a Blake student to be interested in. After my first tutorial this term I said: ‘I shall be reading Sidney and Lyly this week, and will probably bring you a paper on Fulke Greville: is that all right?’ He said: ‘Er—oh, yes—certainly—except that I haven’t read much Greville—Aldous Huxley is very interested in Greville: he started talking about him once, and all I could muster in the way of quotation was’—he quoted two lines—‘it wasn’t much, but I think I had even that counted to me for righteousness.’ Blunden and I are definitely going to get along well this term—he’s used to me now, and probably my manners are better than they were at first. I went to supper with him one night, with Mike Joseph, the Catholic New Zealander, and had a good time. Sherry, white burgundy, and Madeira. Mrs. Blunden is small, dark, Armenian, and intentionally vivacious, with large brilliant eyes and a kind of electric intelligence that turns on and off. . . . Fulke Greville has been keeping me busy—like Blake, his religious, philosophical & political views are all in one piece, and it would take at least a month’s solid work to read all of him and tie him all up in a neat little sack. I had only a week—there’s no good modern edition (Roy wants to do one, but I’m afraid various people are beating him to it) and there was a baldheaded johnny who had reserved all the books in the Bodleian, so I had to beg all the books from him. I had one of my seizures, and worked every day until my eyes gave out for a week on that paper. Blunden liked it very much, I think. These essays I’m doing are mostly publishable, I should imagine: certainly I’ve collected a lot of material for future books.” (3 February 1937)

“I read my anatomy paper to Blunden last night. He said I had two hundred very saleable pages there, but that Jane Austen’s admirers would just read my one sentence on her and conclude that there was rape afoot. He lives, somewhat like Ned Pratt, in mortal terror of the scholars, including at times me. It’s probably the effect of living with Nichol Smith. Anyway, he asked me what he should lecture on next term, so I drew up all the harmless names I could think of in the 17th c: he said he was tired of the 18th and 19th and was afraid of the scholars of the 16th” (9 February 1937).

“Blunden I’ve stopped writing papers for—we’ve become quite good friends. He was complaining yesterday that anthologists seemed to be interested only in his very early poems, and said that most people on meeting him expected to see a rustic of sixty‑five [Blunden was 40 at the time]. He’s a shrewd lad: I told him I wanted to write an essay on the Piers Plowman poems after I got through with Blake, as they were the nearest thing to the Blake Prophecies in English literature. He told me I’d have to learn to edit texts, and said if I could prefix my essay on the Piers Plowman poems to an edition of them, however bad, I might make fifty pounds, but if I just published the essay I’d be ‘out three pounds nineteen six and several drinks’” (9 March 1937)

[A later post will excerpt some passages from the correspondence about Blunden from Frye’s second year at Oxford.]