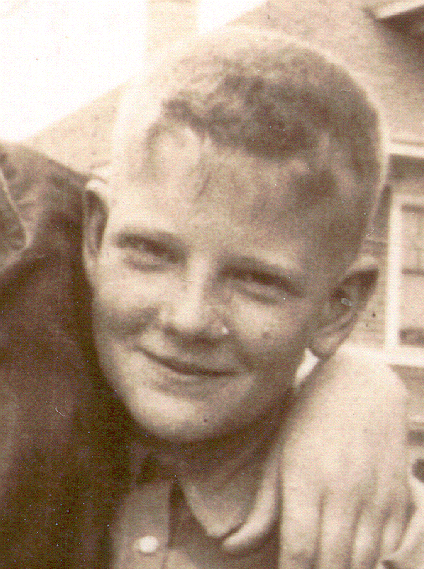

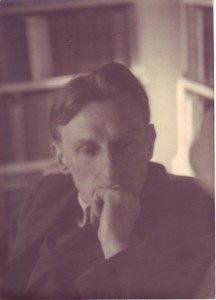

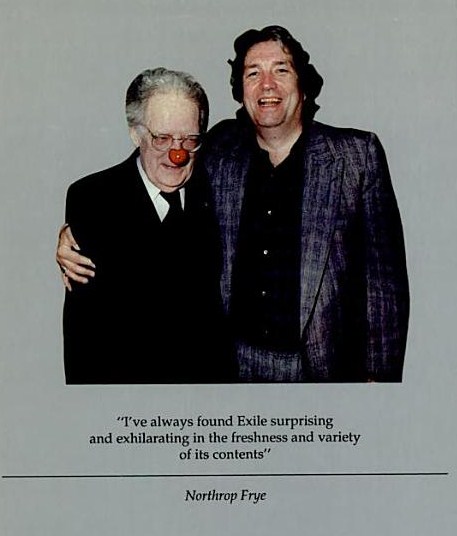

Frye and Barry Callaghan on the back cover of Callaghan’s memoir, Barrelhouse Kings.

Today is Frye’s 99th birthday, which means we’re in the run-up to what will undoubtedly be an eventful centenary.

Looking back at our posts for Frye’s 98th birthday on July 14, 2010, we’re reminded what a busy and eventful time it was.

First of all, it occurred during a rising storm of protest after the University of Toronto announced the closing of the Centre for Comparative Literature, which was founded by Frye. The closure was eventually cancelled, in large part through the efforts of highly dedicated people, like our own Jonathan Allan. Our first post of the day, therefore, was a letter from Bob Denham to U of T President David Naylor, offering support for the Centre.

Next up was a compilation of birthday entries from Frye’s personal diaries, as well as many more letters to his fiance, Helen Kemp, covering the period 1932 to 1950; and, finally, selections from his notebooks at the other end of his life.

There then followed a post about the legacy and continuing importance of the Centre for Comparative Literature from Jonthan Allan.

Then came an update from Dawn Arnold of the Frye Festival on the competition for funding of a community project. Moncton’s proposal was to raise a statue of Northrop Frye to sit in front of the Moncton Public Library, an institution Frye worked for in his youth. The bid did not succeed, but it was very close. I remain hopeful that, with the centenary approaching, the good people of Moncton will somehow get their wish.

That was followed by a birthday greeting from reader Tamara Kamermans, in the form of a novelty video of the Beatles playing “Birthday.”

Finally, a post to round out an eventful day: an announcement that the website was now on Facebook, and a further announcement of a new addition to our journal, a paper by Ken Paradis.

This is a good time to remind readers that we have a dedicated category, Call for Papers, which includes solicitations related to the centenary. We also have a separate category, Frye Centenary, which we expect will fill with more content as the year progresses.

There’s obviously a story attached to the wonderful photo above, and you can read it after the jump. As it was Alice Munro’s 80th birthday the other day, it’s nice that she appears in it too, along with a number of other Canadian luminaries.