The Centre for Comparative Literature is proud to present two lectures by Northrop Frye Professor in Comparative Literature for 2010-2011, Carol Mavor: Wednesday March 9 and Thursday March 10, 5:30, Jackman Humanities 100.

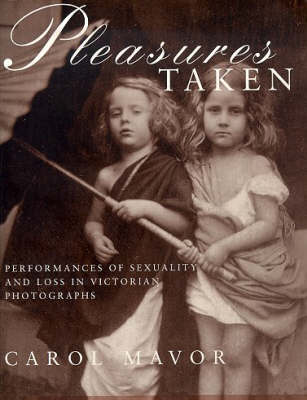

Carol Mavor is Professor of Art History and Visual Studies at the University of Manchester, England. Mavor is the author of four books: Reading Boyishly: Roland Barthes, J. M. Barrie, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Marcel Proust, and D. W. Winnicott (Duke UP, 2007), Becoming: The Photographs of Clementina, Viscountess, Hawarden (Duke UP, 1999), and Pleasures Taken: Performances of Sexuality and Loss in Victorian Photographs (Duke UP, 1995) and Black and Blue: The Bruising of Camera Lucida, La Jetée, Sans soleil and Hiroshima mon amour, is forthcoming from Duke UP (2011). Her essays have appeared in Cabinet Magazine, Art History, Photography and Culture, Photographies, as well as edited volumes, including Geoffrey Batchen’s Photography Degree Zero and Mary Sheriff’s Cultural Contact and the Making of European Art. Her most recent published essay is on the French child-poet Minou Drouet.

Mavor’s writing has been widely reviewed in publications in the U.S. and U.K., including the Times Literary Supplement, the Los Angeles Times, and The Village Voice. She has lectured broadly in the US and the UK, including The Photographers’ Gallery (London), University of Cambridge, Duke University and the Royal College of Art. For 2010-2011, Mavor was named the Northrop Frye Chair in Literary Theory at University of Toronto. Currently, Mavor is completing Blue Mythologies: A Study of the Hue of Blue (forthcoming from Reaktion in 2012).

Blue Mythologies is a visual, literary and cultural study of the color blue. Blue is a particularly duplicitous colour. For example, blue is often associated with opposites or near opposites: like joy and depression; or the sea and the sky; or infinite life and death. Mavor’s approach is semiological, as prescribed by Roland Barthes’s Mythologies (1953). “Mythology,” because it is truth disguised as fiction and fiction disguised as truth, is, by definition, as duplicitous as blue. The subjects are mostly Anglo-European and include a full range of blues: Chantal Akerman’s 2000 film La Captive; the Aran islands off the coast of Western Ireland; cyanotypes and blue Polaroids; the Australian Satin Bowerbrid; Agnes Varda’s 1965 film Le Bonheur; Roger Hiorns Seizure, the 2006 installation of copper-sulfite crystals grown to cover an entire London bed-sit; Krzysztof Kieslowski’s 1993 film Blue; Werther’s Goethe (1774), Novalis’s Henry von Ofterdingen (ca. 1799-80) and Bernardin’s Paul et Virginia (1787). Nevertheless, the research includes blue in non-Western contexts: for example, Krishna’s blue skin in eighteenth-century Jodhpur painting or the powder-blue burqas in Samira Makhmalbaf’s 2003 film, At Five in the Afternoon.