With the U.S. presidential elections coming up, Frye’s comments on elections in general might help see the hoopla for what it is. One quotation is from a special lecture and the other is from an American interview with Bill Moyers. Enjoy.

It has been said that those who do not learn history are condemned to repeat it: this means very little, because we are all in the position of voters in a Canadian [or American] election, condemned to repeat history anyway whether we learn it or not. But those who refuse to confront their own real past, in whatever form, are condemning themselves to die without having been born.

(Creation and Recreation: 1980)

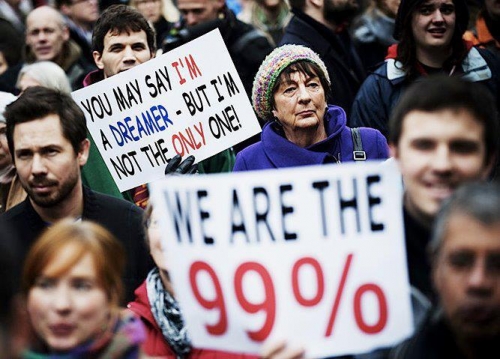

MOYERS: Is television here influencing politics the way it is in the United States, making it a sporting event or entertainment?

FRYE: Very much so. I would like it better if I thought we had people who could play up to it. On the other hand, it doesn’t matter all that much who’s president of the United States. What did it matter in twentieth-century history that George [Gerald] Ford was a President of the United States?

MOYERS: Are you saying that the President is the front man for a system that continues to operate irrespective of his leadership?

FRYE: I’m not sure that the pyramid myth, the notion of the man at the top of society, really conforms to the realities of twentieth-century life. There is a whole machinery that is bound to continue functioning, so that ninety-five percent of what any President can do is already prescribed for him – unless he’s a complete lunatic. For that reason, it doesn’t seem so profoundly significant who is in the position of leadership.

MOYERS: What does that say about the role of the leader in the modern world?

FRYE: It means that the leader has to be a teammate. The charismatic leader, to the extent that he is that, is a rather dangerous person if he starts taking himself seriously. I’m a little leery about the adulation bestowed on Gorbachev. He has a very complex piece of machinery to try to help operate. The historical process works itself out in ways that really don’t allow for the emergence of a specific leader. It’s only in the army that you have the specific leader because that’s the way the military hierarchy’s set up.

MOYERS: But historical processes are the accumulated actions of autonomous individuals expressing their wills, appetites, desires, passions in the world out there. Those are subject to being changed by leaders, are they not?

FRYE: People are much more pushed around than that by the cultural conditioning in which they’re brought up and the social conditions under which they have to operate. The person who emerges as leader is really the person who is the ultimate product of that social conditioning.

MOYERS: There was an Italian Marxist in the 1920s who said that in the future all leaders will be corporate. There will not be single leaders. Of course that was before Mussolini and before Hitler.

FRYE: He was right to the extent that the charismatic single leader turned out to be a disaster.

MOYERS: So maybe the corporate Leader is not only an historical necessity, but a desirable phenomenon as well.

FRYE: He’s desirable because I think he’s essential for movement in the direction of peace. When I said that it was only the military that gives you the person on top, the supreme command, you notice that the dictators, the supreme leaders, have always been leaders of an army and have always imposed what is essentially martial law on their communities.

(Bill Moyers: A World of Ideas, 1989)