Archetype Spotting as Creative Writing

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins has replaced The Da Vinci Code as the model/paradigm of creative writing by such popular creative writing teachers/authorities as Randy Ingermanson (Writing Fiction for Dummies 2010) and Larry Brooks (Story Engineering 2011 and Story Physics 2013).

Northrop Frye’s method of creative writing would add an extra dimension to their teachings. Frye would simply show how Collins’ re-wrote myths, or in his term, “displaced” the myths. The archetypal recipe for The Hunger Games:

1) The Reaping (Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery)

2) the 12 Districts tributes/maze (Theseus and the Minotaur)

3. the arena/human-hunting-humans (Richard Connell The Most Dangerous Game)

4. telescreens (George Orwell 1984)

5. Katniss bow/arrow and helpers (Robin Hood).

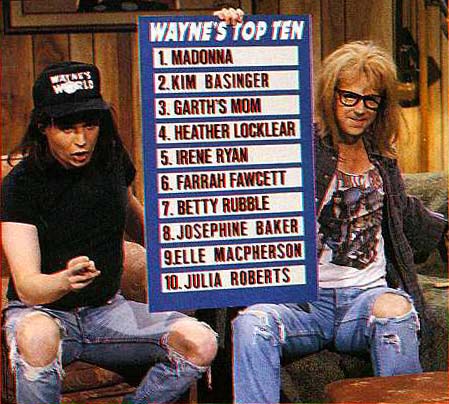

Most creative writing teachers simply adapt Joseph Campbell’s monomyth (like Frye’s genre of Quest-Romance). When I approached Ingermanson and Brooks about Frye’s archetypal spotting/writing technique with The Hunger Games, Ingermanson could not use it; Brooks found it interesting but not instructive. Clearly what is needed is an illustration of archetypes on a micro-scale, a smaller version of what Prof. Glen R. Gill did on a macro-scale with Steven Spielberg’s films spotting the biblical archetypes (posted previously) :

1. Genesis (Jurassic Park; A.I.)

2. Exodus (Schindler’s List)

3. Job (Minority Report)

4. Gospels (E.T.)

5. Jonah (Jaws)

6. Revelation (War of the Worlds).

While The Educated Imagination lectures brim with archetypes of setting, character and plot, perhaps what is needed is a formulaic listing of archetypes broken down into the parts of a story, like Freytag’s Pyramid scheme (exposition, rising action, climax, falling action and denouement) or Syd Field’s 3 act structure of scriptwriting (setup, confrontation, resolution).

Both creative writing authors, Ingermanson and Brooks, basically use the screenwriting paradigm for fiction as popularized by Syd Field 3 act structure. Ingermanson’s variation on this model is to write 3 disasters prior to the deciding final climax in act 3. Brooks’s method converts Field’s 3 acts into 4 acts (the Confrontation in act 2 is split in half) and he marries character development on top of the 4 acts/plot, as the main character goes through the stages of Orphan (act 1), Wanderer (act 2) , Warrior (act 3), Martyr (act 4).

The closest model to Frye’s (using Frye’s method of 3 identities, individual, dual and social) is the author of the storywriting software Dramatica. Again, even that elaborate method could benefit from archetypal spotting, For now, without the input of Frye’s ideas (displaced archetypes or even type-anti-type typology), creative writing teachers will be missing an extra dimension to their teachings.