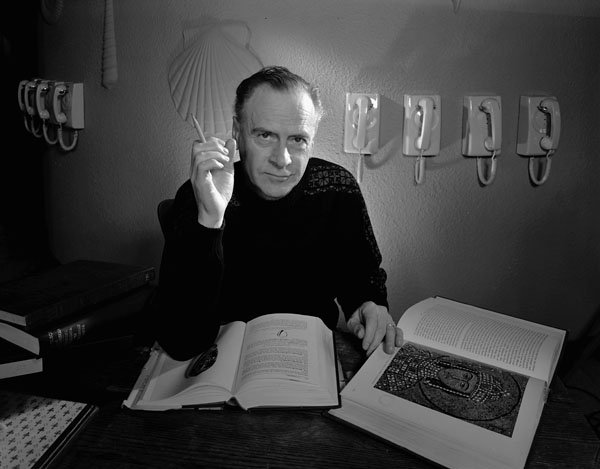

A great deal has been made of the claim that Frye and McLuhan were rivals. But were they? W. Terrence Gordon’s Marshall McLuhan: Escape into Understanding: A Biography says twice that they were rivals, without indicating any basis for the claim. Philip Marchand’s Marshall McLuhan: The Medium and the Messenger (Toronto: Random House, 1989), takes a different view, showing McLuhan to be jealous of Frye’s eminence and noting several small-minded actions on the part of McLuhan to chip away at that standing. Take for example this episode from Marchand’s biography:

A panel of graduate English students was organized by the Graduate English Association at the University of Toronto to discuss Frye’s book [Anatomy of Criticism] shortly after its publication. One of the panellists, Frederick Flahiff, recalls, “One morning after the announcement of the panel had gone out, Marshall appeared in my room carrying a copy of [an] essay entitled “Have with You to Madison Avenue; or, The Flush Profile of Literature.” The essay, written by McLuhan, was an attack on Frye’s criticism as the formation, via literature, of a perceptive mind to a pseudo‑scientific charting of the features of literature vaguely analogous to Madison Avenue profiles of consumer groups (“Flush profile” is a reference to a method of measuring viewer response to radio and television programs by gauging the incidence of toilet flushing. [“Flush Profile” is reproduced below.]

McLuhan was not at his best in this essay. His argument, studded with tortured metaphors, was extremely convoluted, and would have succeeded in confusing any audience, no matter how well versed in Frye’s book. One thing was clear though: no one but McLuhan could have written it. Nonetheless, McLuhan asked Flahiff if he would read the essay on the panel as if it were his own response to Frye. We went out and walked around and around Queen’s Park, Flahiff recalls.

McLuhan was at his most obsessive. I don’t mean that he was hammering away at me to do this thing, but he was obsessive about Frye and the implication of Frye’s position in the same way he had talked about black masses. It was the first time I had seen this in McLuhan––or the first time I had seen it so extravagantly. As gently as possible I indicated that I could not do this and that I was going to write my own thing. . . . Later, on the night of the panel, he phoned me before my appearance and asked me to read to him what I had written. I indicated that he could come to the session if he wanted, but he said “Oh, no, no.” (105–6)

Marchand also reports on a letter from McLuhan to a close friend in which “McLuhan mentioned Frye’s leaving Toronto for a conference and added that he hoped Frye would not bother to return” (105). Perhaps McLuhan did see Frye as a rival, but I find no evidence in all of Frye’s comments on McLuhan that Frye considered McLuhan to be a rival. Nor does Frye say anything unkind about McLuhan, except perhaps for the remark that McLuhan had a reputation as a great thinker but he didn’t think at all.

If Frye saw McLuhan as a rival it seems doubtful that he would have argued long and hard that McLuhan should be given the governor general’s award for Understanding Media. Or that, as David Staines reports, he would have said to Corrine McLuhan after Marshall’s death, “I always wanted to be closer to Marshall than I was.”

After the jump, McLuhan’s review of Anatomy.