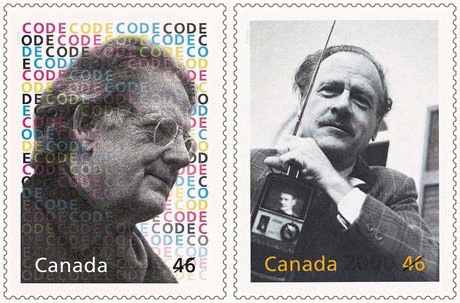

In Anatomy of Criticism Frye notes that critics often break forth into an “oracular harrumph” when they encounter references to alchemy, the Tarot, Rosicrucianism, and the like, and the same attitude persists more than a half‑century later. One encounters readers here and there, having discovered that Frye thought highly of Colin Still’s book on The Tempest or that he had read some esoteric work, recoiling in amazement, as if it automatically followed that Frye was a card‑carrying member of some mystery cult or was engaging in the ritual practices of Freemasonry. In the late 1970s I was invited to a party in Toronto by a friend at York University, where the assembled party‑goers turned out to be McLuhanites. When they discovered that I had an interest in Frye, they began to pepper me with questions about Frye’s having been a Mason. I naturally asked what evidence they had for this claim, but none was forthcoming, their assumption being that this was common knowledge. The rumor, apparently, was initiated by Marshall McLuhan, or at any rate perpetuated by him. McLuhan’s biographer Philip Marchand writes that McLuhan “certainly never abandoned his belief that his great rival in the English department of the University of Toronto, Northrop Frye, was a “Mason at heart, if not in fact” (Marshall McLuhan, 105). In a book review Marchand removes the qualification, saying flatly that “McLuhan thought Frye was a Mason” (Toronto Star, 30 November 2002). He goes on to say that it’s no wonder that McLuhan suspected that Frye was a Mason because (check out this logic) he was interested in the occult, used diagrams, and, heaven help us, took Colin Still’s Shakespearean criticism seriously.

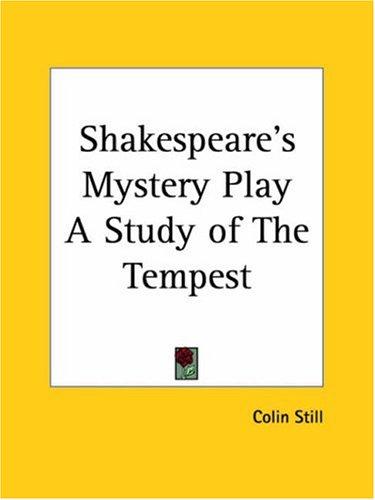

“Colin Still,” Marchand declares, “was a crackpot,” whose book on The Tempest “[m]ost academics would have been embarrassed to be seen reading.” Really? This is an example of a little learning having turned into ignorance. Marchand has no sense of allegory, and he has no sense of the difference between the reading of a text and the use to which that reading is put. All this gets picked up by Colby Cosh, who does Marchand one better: “The crushingly excellent Philip Marchand has a mesmerizing column about the poisonous rivalry between Marshall McLuhan and Northrop Frye. . . . McLuhan, a conservative Catholic, despised Frye because he thought he was dabbling in dark occultic forces and perhaps messing about with Freemasonry. . . . Marchand has discovered a new and major source for Frye’s thinking in Colin Still, a hitherto undistinguished flake who believed The Tempest was a disguised representation of some sort of pagan initiation rite” (ColbyCosh.com. 30 November 2002).

Although Frye occasionally comments on Freemasonry (e.g., the Masonic overtones of The Magic Flute, the Masonic links with the trade unions in the nineteenth century, the affinity between the Freemasons and the Royal Society, and the Freemason scapegoat myths), there is not a shred of evidence that Frye was a Mason. As for Still’s being a “crackpot” and an “undistinguished flake,” no less a critical intelligence than R.S. Crane speaks of the “pioneering work” of Still in reading Shakespeare allegorically, discovering in the play “the double theme of purgation from sin and of rebirth and upward spiritual movement after sorrow and death” (The Languages of Criticism and the Structure of Poetry, 132). Peter Dawkins refers to Still as an “eminent scholar” (The Wisdom of Shakespeare in “The Tempest,” xxv), and Michael Srigley has defended Still’s thesis (Images of Regeneration). Ronald Tamplin finds in Eliot’s The Waste Land “a pattern corresponding in outline, imagery, and incidental material to Still’s account of initiation into the Greek mystery religions” (American Literature 39 [1967]: 361). In a detailed examination of Still’s argument, Michael Cosser says, “Certainly it is not stretching credulity to see a close parallel between the play and what can be pieced together from classical sources as to the training received in the Mystery-centers of old” (Sunrise 49 (December 1999–January 2000). And in his study of the sacerdotal features of The Tempest my colleague and friend Robert Lanier Reid, though not convinced of the explicitness of Still’s claims, nevertheless takes seriously Still’s view that the play is a “universal purgatorial allegory” (Comparative Drama 41, no. 4 [Winter 2007–8]: 493–513). These critics, like Bishop Warburton before them, are far from being crackpots and flakes. In the eighteenth century Warburton, as both Still and Frye were aware, had proposed the theory that book 6 of the Aeneid––the descent to the underworld––corresponds to the ancient rites of initiation. In other words, observations about parallels between literary works Greek initiations rites had been around for some time: noting such parallels was a common critical practice.

Still’s books, listed in all the bibliographies, were also celebrated by the distinguished Shakespearean G. Wilson Knight, who calls Shakespeare’s Mystery Play an “important landmark” (Shakespeare and Religion, 201). As an undergraduate at Victoria College, Frye had known Knight, who taught at Trinity College at the University of Toronto in the 1930s. T.S. Eliot referred to Still in his preface to Knight’s The Wheel of Fire, and it is possible that Frye ran across this reference even before he checked Still’s book out of the Toronto public library during his sophomore year in college––the same year that The Wheel of Fire was published (1930). In The Wheel of Fire Knight writes, “Since the publication of my essay, my attention has been drawn to Mr. Colin Still’s remarkable book Shakespeare’s Mystery Play . . . . Mr. Still’s interpretation of The Tempest is very similar to mine. His conclusions were reached by a detailed comparison of the play in its totality with other creations of literature, myth, and ritual throughout the ages” (16). Knight regards Still’s book as confirmation (“empirical proof”) of his own view that The Tempest is a mystical work (ibid.). A year later Knight wrote that his view of The Tempest

is most interestingly corroborated by a remarkable and profound book by Mr. Colin Still, Shakespeare’s Mystery Play: A Study of the Tempest (1921). . . . Mr. Still analyses The Tempest as a work of mystic vision, and shows that it abounds in parallels with the ancient mystery cults and works of symbolic religious significance throughout the ages. Especially illuminating are his references to Virgil (Aeneid, VI) and Dante. His reading of The Tempest depends on references outside Shakespeare, whereas my interpretation depends entirely on references to the succession of plays which The Tempest concludes. We thus reach our results by quite different routes: those results are strangely––and, after all, I believe, not strangely––similar. To the skeptic this may suggest that mystical interpretation of great poetry may be something other than Horatio’s (Hamlet, I. V. 133) ‘wild and whirling words’. It is not without its dangers, yet it is the only adequate and relevant interpretation of Shakespeare that exists; since, if the vision of the poet and that of the mystic are utterly and finally and in essence incommensurable, where are we to search for unity? And yet if the art of poetry has its share of divine sanction and transcendent truth, what limit can we place to the authentic inspiration of so transcendent and measureless a poet as Shakespeare?” (Shakespeare and Religion, 67–8)

Marchand and friends are of course free to say whatever they wish about the interpretations of Still, Knight, and Frye, though one wishes that their dismissals had not been based on such ill-informed opinions about the parallels between Shakespeare and ancient myth and ritual.

Previous posts on Frye and McLuhan here, here, here, here, here, here, and here. The complete McLuhan thread here.