Some days ago, I sent out letters requesting information on professors who take an active, scholastic interest in Northrop Frye. I have a BA in Comparative Literature from UC Santa Barbara, and am looking for English graduate programs where I may incorporate Frye’s diagrammatic method into specific research. Professor Adamson has kindly invited me to post something here about how my interest in Frye arose in part through working as a teacher with orthopedically handicapped students.

My experience with such students is a product of my work as a substitute teacher in the greater Los Angeles area. It is difficult to obtain consistent teaching assignments now, especially considering our certain governor’s propensity for terminating education funds. I have therefore found more work with less orthodox students, which is something to which my father has devoted his entire teaching career.

My work in one of these classes coincided with some cursory reading of [Roman] Jakobson]. I was taken with Jakobson’s model of metaphor and metonymy, based on his work with language acquisition and aphasia. While my interaction with students was not nearly as systematic, it greatly reinforced my sense of the metonymic workings of language acquisition. When a child is learning to read, an unknown word is often sounded-out, and then replaced with a known word that rhymes with those sounds- sip becomes ship, cot cat. I can recall a student named Elijah who had had clustered brain tumors as an infant. He would tell stories structured only on a series of metonymy- What did the monkeys do next? They attacked the car. What did they say? They ate me! What happened then? I fed them pizza and chicken! This of course does not do justice to Elijah’s stories. They were products of an outrageous and brilliant associative process that defied logic, space, and mortality. While the origins of many of the images (a TV show? The expected vandals in his neighborhood?) were private and beyond communication, many of them were contiguous images, constantly displaced into the unfolding narrative.

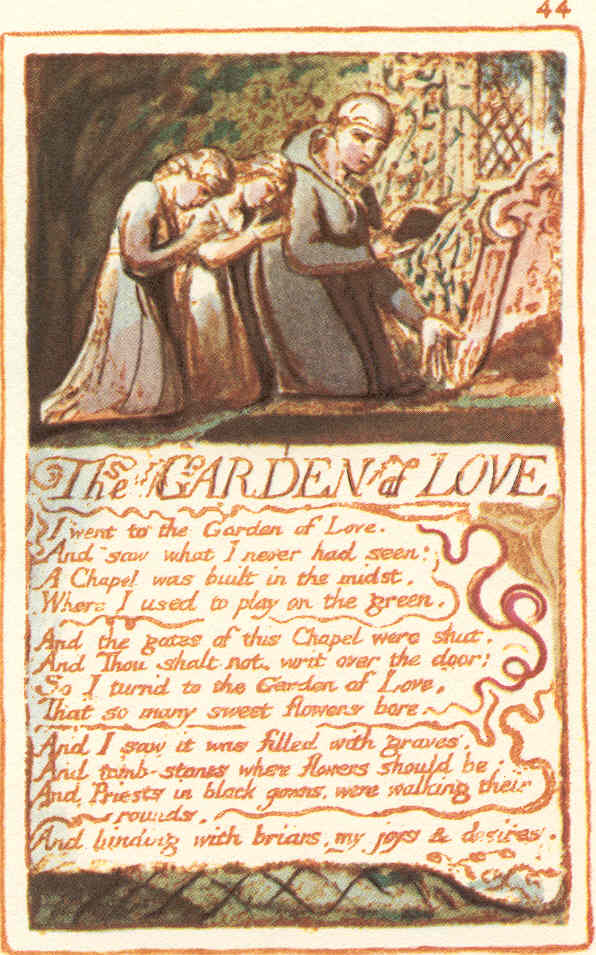

While I am not an expert in cognitive science, or in cognitive approaches to narrative, my experience with Elijah certainly made me very receptive to Frye’s distinction between centrifugal and centripetal forms of criticism. In Elijah’s stories, the etiological and centrifugal origins of the plot and characters were subordinated to the centripetal patterns of the narrative. It was in the telling of those patterns that he found extreme communicative joy and liberation of imagination. Near the penultimate page of the Anatomy, Frye writes, “The link between rhetoric and logic is ‘doodle’ or associative diagram, the expression of the conceptual by the spatial” [335, Princeton edition]. The only way of decoding what in Elijah’s stories made him laugh was to follow the logic of “babble,” to trace the imaginative puns and metonymic displacements of imagery.

What had initially brought me into Comparative Literature was my interest in the revelatory symbol, and how one may understand the processes and degrees of symbolization at work in such varied writers as Spenser and Joyce. I now find most useful those dialectical oppositions that do not act as privileged dichotomies, but rather as polar continuums, allowing for maximum modulation and movement. What seems uniquely powerful about Frye’s schemata is his capacity to set such integral distinctions while displacing them into his modal diagrams. His passage in the Anatomy on babble and doodle, the radicals of melos/opsis [270-81], is one of the few examples I know of a critic assimilating the rudimentary and associative nature of linguistic development into a broader, synoptic view of literature. A critic, whom I cannot remember any more, wrote that one drawback to Frye is that he does not establish an etiological theory of linguistics. The lack of a theory of such a priori things (which may have something to do with negative capability) in no way diminishes his achievement of establishing schematic first principles to literature; first principles that may be modified as suits the subject.

The conceptual by the spatial, so totalizing in Frye, is a pragmatic and teachable method of scholarship which I hope to pursue in my graduate studies, wherever those shall be. The above does not sum up my reasons for wishing to undertake a study of Frye and his applications to modes of symbolism, but it does note the more humane and fundamental values I perceive in him.