This article is cross-posted in the journal here

The odyssey of my editing Frye’s previously unpublished writing began in the summer of 1992 when I arrived at the Victoria College Library to examine the Frye papers that had been deposited there following Frye’s death in January 1991. I had the good fortune of working with Dolores A. Signori, who had been enlisted to compile a guide to the Frye papers. Eva Kushner, president of Victoria College, had set me up in one of her offices on the second floor of the E.J. Pratt Library. Every day, Dolores, who was working down the hall, would bring me a cartful of documents to examine, and my more of less self‑defined job was to see if I could identify the various items. The Frye papers comprised a substantial body of material––occupying more than twenty‑three meters of shelf space. What I combed through initially were the “literary files,” as they came to be designated in Dolores’s Guide to the Northrop Frye Papers (Toronto: Victoria University Library, 1993), and among the “personal files,” Frye diaries. I was also keenly interested in Frye’s correspondence with his Helen Kemp, his girlfriend and later wife, in the 1930s and in the typescripts of his student essays. These were the four main categories of documents that I focused on. Among the literary files were Frye’s notebooks, as well as published addresses, lectures, and essays. I fairly quickly determined that the Frye papers contained a large amount of extraordinary material, and I was convinced that a good portion of it should be published. Thus began my sixteen‑year odyssey.

The initial challenge was to see, for the holograph material, whether or not I could successfully decipher Frye’s handwriting. I remember carrying a photocopy of one of the notebooks––it was on Matthew Arnold––back to my room in Burwash Hall to see if I could transcribe it. I managed to decipher only about half of the text, and so initially I rather despaired of ever being able to reproduce with any degree of certainty what Frye had written. But the idiosyncrasies of Frye’s script gradually became more and more distinguishable, and eventually I was able to read his handwriting with a fair amount of confidence. Frye’s orthography remained very consistent over the years, so once I learned the features of his graphemes, it was only occasionally that I would be stumped by a word or phrase.

I convinced myself early on that the notebooks, diaries, student essays, and Frye–Kemp correspondence should be published. But there was a problem with half of the correspondence––Kemp’s letters to Frye could not be located. John Ayre had used some of Frye’s letters to Kemp in writing his biography of Frye and he knew of the existence of Kemp’s letters to Frye, but I could not find these letters, nor could Jane Widdicombe, Frye’s secretary and the executrix of the Frye Estate, locate them at the Fryes’ Clifton Road home. So during that first summer I called Frye’s second wife, Elizabeth, to see if she would permit me to search for the papers in the attic. She graciously consented. But shortly after that I learned that she was not well. Although I knew Elizabeth and had spent some time with her and Frye in Toronto and Washington DC, I decided it would not be proper for me to be rummaging around in the home of one who was showing signs of dementia. At that point I contacted Ian Morrison, Elizabeth’s son-in-law, who agreed to look through the papers in the attic. Within several days he drove to the Vic campus, and, as in a scene from a James Bond movie, opened the trunk of his sleek sedan and delivered to me an attaché case and several dusty shopping bags filled with files, photographs, sketch books, postcards, newspaper clippings, and other miscellaneous documents. Rummaging through this material, I was almost ready to conclude that Kemp’s letters to Frye had not been preserved, but at the bottom of the last shopping bag I finally uncovered them. Helen Kemp has very carefully clipped the envelopes to the letters and had made notes on some of them, presumably for John Ayre’s benefit. In any event, I now had 266 letters, cards, and telegrams that passed between Northrop Frye and Helen Kemp from the winter of 1931–32 until 17 June 1939, and I decided that the first project I would tackle would be the transcription of the Frye–Kemp correspondence.

The size of the entire project was almost overwhelming, but I set out to photocopy whatever I thought was worthy of eventual publication. This was, in addition to the correspondence, chiefly the seventy-seven notebooks that turned up, the seven diaries, and a number of typescripts of Frye’s talks, student papers, and essays. The Victoria library staff had been gracious in accommodating my needs, but the photocopying proved to be something of a frustration as the machines in the library produced such poor copies. Robert Brandeis, the chief librarian, has provided me with a key to the library so that I could get in and out of my temporary office at night (the library was not open in the evening during the summer). So for several weeks I would fill my book bag with notebooks and diaries, haul them across campus to one of the photocopiers in the Robarts Library, and stand there for hours feeding dimes in to the machine. This was doubtless against library policy (I was afraid to ask for fear I would not be permitted to take the manuscripts from the library), but I was eager to take back to Virginia copies I could read, and the chance that I would be hit by a truck, scattering the Frye manuscripts along St. George Street, seemed fairly remote. I have no idea how many pages I copied altogether, but the thirteen volumes of previously unpublished material that eventually made their way into the Collected Works amount to almost 7,000 pages.

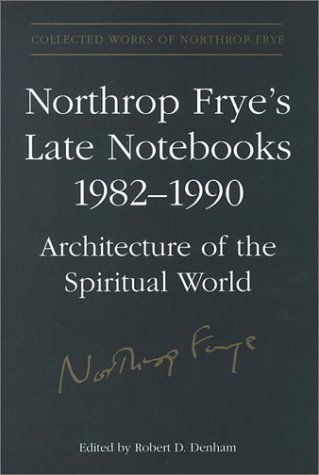

Word of this treasure trove of began to seep out, and some of those attending the conference on the Legacy of Northrop Frye, held at Victoria during the fall of 1992, began to examine the material in the Frye “fonds,” a word, new to me, that archivists use to refer to a body of material in special collections. I began to get the sense from some quarters that as a foreigner I was usurping an editing project that properly belonged to Canadians. The Frye material, it was suggested, was of sufficient scope to keep an army of Toronto graduate students busy for years. So what business did I have hauling copies of these treasures back to Virginia? It was at this point that I asked for permission from Jane Widdicombe and Roger Ball, executors of the Frye estate, to edit and publish all of Frye’s previously unpublished manuscripts and documents. The permission was granted with the proviso that the executors would have final approval of the publisher. I had been Frye’s unofficial bibliographer for a number of years, and in the late 1980s he had permitted me to edit three volumes of his essays and a collection of interviews. The executors had earlier granted permission for me and Michael Dolzani to edit Frye’s professional correspondence, which had been coming to the Victoria University library in instalments over a period of years. But with the excitement generated by the notebooks, diaries, and other papers, I decided to put the professional correspondence on the back burner. I asked Michael Dolzani, who had been Frye’s research assistant for twelve years and was more knowledgeable about Frye’s work than anyone else, to help me edit the unpublished material. He agreed, and we set about the painstaking process of transcribing and annotating the photocopied documents. In 1995–96 I received a year‑long NEH fellowship, which meant that for an entire year I could devote full time to the project. Five years later Michael and I had a large portion of the manuscripts in electronic form. Once we had most of the transcription completed we began assigning the material to particular volumes. I elected to begin with Frye’s late notebooks, written mostly during the 1980s, and Michael initially tackled what came to be known as The “Third Book” Notebooks, Frye’s free‑wheeling speculations about the book he intended to write after Anatomy of Criticism but never did.

In the meantime, a proposal had emanated from Victoria College, spurred by the leadership of President Eva Kushner, to produce a collected edition of Frye’s works. The issue now was whether or not the previously unpublished documents would become a part of this project. By 1994, I had completed the transcription of the Frye–Kemp correspondence, a document of more than 400,000 words. At a meeting at Victoria College of President Kushner, the executors, Ron Schoeffel of the University of Toronto Press, and myself, I agreed that the best course was to join my efforts with the Collected Works project. I had not had a very happy experience with the publication of my Frye bibliography with the U of T Press, and so I sought some assurance that there wouldn’t be the kind of foot‑dragging with this project that there had been with the bibliography. I was promised that the manuscript would be published within a year. It took two years. I was naturally eager to have the unpublished material in the hands of readers as soon as possible, but I came to realize there was little I could do to advance the process at the Press, which tended to move slower than a wounded turtle. In any case, the two‑volume Frye–Kemp correspondence was published in 1996 under the general editorship of John M. Robson. And then, sixteen years after I began making a census of the material in the Frye fonds, I completed my commitment to make available to the reading public the previously unpublished manuscripts of Northrop Frye. I ended up editing nine of the thirteen volumes, Michael Dolzani edited three, and we shared the editorial duties for the final volume. Whatever insights we felt were worth reporting appear in our introductions to the several volumes. Each of us took on an additional volume in the series: Michael edited Words with Power and I, Anatomy of Criticism.

There were eureka moments on practically every page of Frye’s manuscripts, and there were larger epiphanies, such as the discovery, when we were well along in the process, of a set to typed notes called “Work in Progress,” which suddenly clarified the history and organizing pattern of Frye’s ogdoad project and its symbolic shorthand––the eight‑book project that motivated so much of his writing career. Then there was the discovery when I was almost finished with the late notebooks of still another notebook, which turned up on the bedside table of in Elizabeth Frye’s nursing home. These notes were the workshop for Frye’s 1990 “double vision” lectures at Emmanuel College. Transcribing and annotating can often become rather mindless operations, but what justified the tedium was watching Frye’s fertile, nimble, and well‑stocked mind at work. It is trite to say that every day uncovered new insights, but it is nevertheless true.

The success of the Collected Works project is due to the devoted labors of many people, including Jean O’Grady and Margaret Burgess at the Northrop Frye Centre, but no one has been so important in insuring success as Alvin A. Lee, who assumed the role of general editor after the untimely death of Jack Robson. Anyone interested in the history of the project should consult Lee’s “The Collected Works of Northrop Frye: The Project and the Edition,” in Northrop Frye: New Directions from Old, ed. David Rampton (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 2009), 1–14. All of us owe an enormous debt to Lee.

The volumes of previously unpublished material:

The Correspondence of Northrop Frye and Helen Kemp, 1932–1939. 2 vols. (Denham)

Northrop Frye’s Student Essays, 1932–1938 (Denham)

Northrop Frye’s Late Notebooks, 1982–1990: Architecture of the Spiritual World. 2 vols. (Denham)

The Diaries of Northrop Frye, 1942–1955 (Denham)

The “Third Book” Notebooks of Northrop Frye, 1964–1972: The Critical Comedy (Dolzani)

Northrop Frye on Literature and Society, 1936–1989 (Denham)

Northrop Frye’s Notebooks and Lectures on the Bible and Other Religious Texts (Denham)

Northrop Frye’s Notebooks on Romance (Dolzani)

Northrop Frye’s Notebooks on Renaissance Literature (Dolzani)

Northrop Frye’s Notebooks for “Anatomy of Criticism” (Denham)

Northrop Frye’s Fiction and Miscellaneous Writings (Denham and Dolzani)