The latest from Mervyn Nicholson, on how Frye was different:

When was the last time you laughed out loud reading De la Grammatologie? or, well, guffawed or chuckled, if not actually laughed? Derrida tickle your funny bone lately? How about Blindness and Insight? Paul de Man was quite a clown, wasn’t he? Or how about Stephen Greenblatt? or Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick? or Judith Butler? lots of LOL there.

You know where this is heading. Frye had a sense of humour! His sense of humour was vivid, witty, lively, incisive, satiric, but also playful. The range of humour is significant, too, because he can be light in tone as well as biting. He is good at coining witty phrases, as everyone knows. The impulse to quote him for those who know his work well is irresistible, especially his numerous satiric and witty remarks. I always laugh when I read Frye. All of his books have humour in them, and clearly the humour was important to him—he made sure to use it.

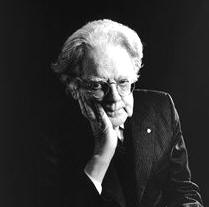

Not only does Frye use humour in his writing, but he was funny in his lectures. Most of his lectures included what might be called jokes—“self-contained verbal structures,” to use his own idiom, that made people laugh out loud. Of course his deadpan manner, his dry and wry style, was not that of a clown: it was definitely that of a great intellectual. He could say funny things without giving any facial cue that saying something funny was what he was doing. But that made the humour funnier, because it came from what had become a legendary professor persona: the figure of the ultimate intellectual. There was always an element of surprise, as if discovering that he was a human being, not just an icon on a pedestal, or someone of such grand pretention that humour must be kept distant from him. Curiously, Frye’s humour never had the effect of undermining or taking away any of the seriousness of what he was talking about. Frye was serious about his humour.

His status as preeminent academic made him a target for hostile comments of the type that Irving Layton specialized in, treating Frye as a dried-up brain without a body—an image totally at odds with the livewire brilliance that Frye displayed. Forget his tweed jacket and nerdy physique—he could be funny. His voice was a perfect instrument—deep and beautifully modulated, with the kind of rhythm that only a musician can achieve—a voice perfect for reading out loud—or for giving lectures. And he was a superb reader. Just as he made a point of saying things that were funny, he made a point of reading out loud in class—including in his graduate classes, something unthinkable in the usual academic milieu inhabited by graduate students and professors suffering from grandiosity issues. But it was important to Frye that people hear the great poets, not just see their work as print marks on a page. Clearly, Frye, the intellectual, believed that learning involved more than arguing over abstractions.

Frye’s humour punctured any pretention that “higher” English studies might demand. The humour shifted attention from the pretention implied by the scene (famous professor lectures naïve novitiates) over to the real point of teaching, namely the content of the class. Frye insisted on this point: the teacher must be “a transparent medium” for the subject, and must never stand between the subject and the students, setting him or herself up to be a kind of idol, someone who receives the attention of the student rather than the subject itself. His humour was important in demoting the professor and enhancing the content. The humorless solemnity of High Theory and the relentless didacticism of the New Historicism are prima facie limited by their lack of this intellectual vitamin.

This point opens up something important about Frye’s humour. It had a function. And this function was not merely to break the ice or release tension. The humour—I am referring now to his writing—is not merely a decoration or a distraction. It always conveys meaning. It is another way of expressing the thought that Frye is working with. Frye was profound in many ways, but one of the most important is his insistence that meaning is communicated in other modes than abstract reasoning or abstract verbal constructs. Meaning is conveyed in non-abstract ways, by means of image and emotion and body. And humour.

By image, of course, I do not mean “symbol”; I mean the sheer act of forming and transforming mental images: the act of visualization. The form/trans/forming of images is a medium of consciousness, of intellection. It is a means of communicating and formulating thought. I explored these issues myself in my own book 13 Ways of Looking at Images [Red Heifer Press, 2003], which is intended to develop and explore Frye’s approach. Thought is not confined to ideas in the sense of abstractions: it is expressed in sensory forms, such as painting and music, but also in forms of mental imagery. Indeed, the key to Blake, he says in Fearful Symmetry, is that “form” and “image” mean the same thing, and if this works for Blake, we can be sure it works for Frye, too—that the image of a thing is the form of that thing.

This is a big conception, too big for a short note, but it is basic Fryethought. Humour is like images: it is a mode of communication, of fashioning and making ideas precise—it is not just a pleasant talent that Frye enjoyed entertaining readers with, though there is nothing wrong with entertaining readers, something that Frye excelled in. You know that well enough when you put down your Derrida or just about anybody else and pick up Frye.

Frye was different, all right.