httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eQpsL_kh6pE

Sonata in C, 2nd movement, Mitsuko Uchida, piano

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eQpsL_kh6pE

Sonata in C, 2nd movement, Mitsuko Uchida, piano

Responding to Peter Yan and Adam Bradley:

Yes, Frye certainly did know about the Greek modes. In “Modal Harmony in Music” he writes:

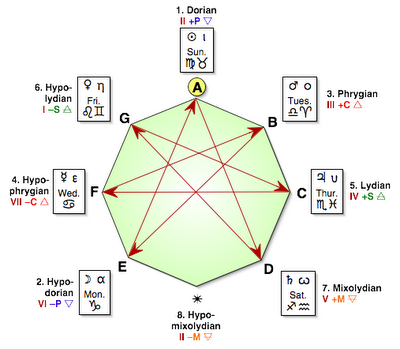

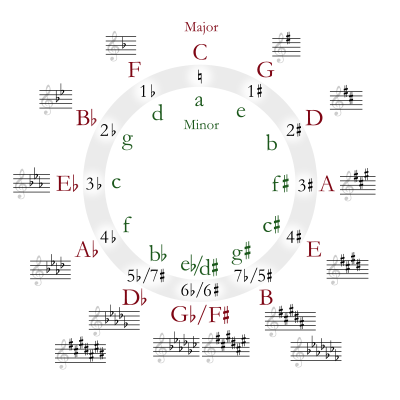

In the sixteenth century much greater freedom of tonality was available. The major and minor modes were then celled Ionian and Aeolian respectively, but four others were used. Arranged in order of sharpness, they are: Lydian (F to F on white notes: present major with raised fourth); Ionian (C to C: present major); Mixolydian (G to G: present major with lowered seventh); Dorian (D to D: present natural minor with raised sixth); Aeolian (A to A: present minor); Phrygian (E to E: present natural minor with lowered seventh). A seventh mode, the Locrian, B to B or Phrygian with lowered fifth, had probably only a theoretical existence. These four additional modes, like the two we now have, ended on the tonic chord. Thus, if all modes were impartially used today, a piece ending on G would have a key signature of two sharps in the Lydian modes, one in the major, none in Mixolydian, one flat in Dorian, two in minor, three in Phrygian. Or a piece with a key signature of one sharp could be C Lydian, G major, D Mixolydian, A Dorian, E minor, or B Phrygian. (Northrop Frye’s Fiction and Miscellaneous Writings, 185)

And in “Baroque and Classical Composers” Frye writes:

When rhythm changes from 4/4 to 3/2 the minim of the latter = crochet of former. Key signatures only either none or one flat, & occasionally two flats: no sharps. Fellowes finally, bless his heart, coughs up some dope on the modes. If the piece has no flat in the signature, look at the last bass note and that will give you the mode. A = Aeolian (minor scale), B = Locrian (theoretically: it’s never used), C = Ionian (major scale), D = Dorian, E = Phrygian, F = Lydian, G = Mixolydian. That’s if the melody is authentic: if it’s plagal then prefix hypo to the mode. If there is a flat, transpose a fourth down or fifth up (G with a flat = D without one); if two, tr. [transpose] a tone up. Hence many key signatures until the 18th c. were a flat or a sharp short. Modulation & equal temperament go together. (ibid., 175)

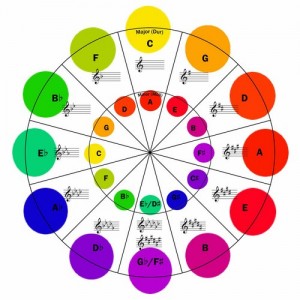

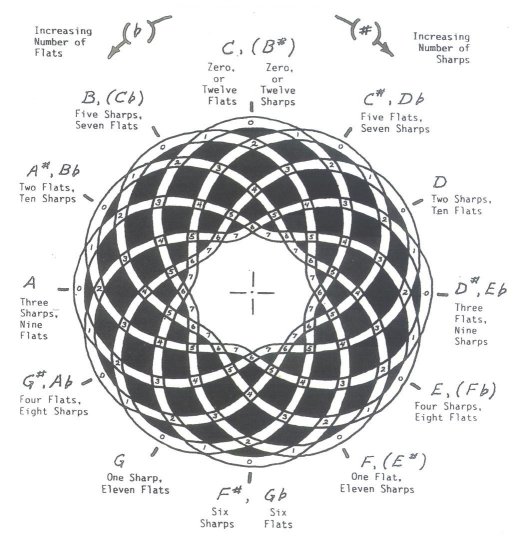

As for the circle of fifths, sometime in the late 1950s or early 1960s Frye provided a schematic for the circle as a way of outlining the twenty‑four parts in the first three units of his ogdoad: Liberal, Tragicomedy, and Anticlimax. The twenty‑four letters of the Greek alphabet provided Frye a convenient name for each of the twelve major and the twelve minor keys. C = alpha, A = beta, G = gamma, etc. Frye didn’t actually draw a diagram, but in his Notebooks for “Anatomy of Criticism” (paragraphs 57, 58, 63, and 73 of Notebook 18), he set down the constituents of a diagram and gave a brief description of the thematic contents of each of the twenty‑four parts, illustrating what he means by saying that the circle of fifths provides a “symmetrical grammar” (Spiritus Mundi, 118).

Peter, I think that your observation regarding the term ‘Mode’ is very interesting and may actually be quite important.

The title Anatomy of Criticism always struck me as being peculiar because it suggests that Frye was conscious of the fact that he was beginning the process of laying out the structure of literary theory. By using the word “anatomy,” its seems to me he was indicating that we were in the beginning stages of this type of analysis simply because in medicine the cataloguing of the parts of the body was a necessary step to understanding the processes of the body.

I agree with you that, when laying out his theory of literature and the circles of fifths, Frye must have made the association between the Quest Romance and the key of C for a reason. I have been thinking about the circle of fifths and literary theory since the first post on this blog, and the use of the word ‘Mode’ suggests to me that Frye had an even grander vision for how his anatomy crossed over to all forms of art.

That said, I balked a bit at the suggestion that Frye picked the key of C as an equivalent for the Quest Romance because it is the key which all keys can be translated into. I think we need to tread lightly when trying to decipher why he would do that. Frye, being a fan of classical music and a piano player, would have surely known his scales but to say that its the “key which all keys can be translated into” is a little misleading. We can transpose any piece of music freely between all keys; they are interchangeable. But I do think you are onto something, I simply wonder if it is more that the key of C has no sharps or flats, and that it is the most naturally organized key in our theory of music and on our keyboards. The idea that all other keys are expressed as functions of the key of C does not mean that the key itself or more specifically the sounds made in the key of C are any more important than those of any other key. The key of C is simply our home base, and it permeates our thinking about music as being the solid foundation which we build upon.

I wonder if that is closer to the connection that Frye was trying to make when assigning it to the Quest Romance genre. I think if we look at Frye’s explanation of that genre, we may find that the other genres that he talks about all use the Quest Romance as their frame of reference, just as all the musical keys refer back in our theories to the key of C. As for the modes of music, all the modes can be built in all keys — they apply to every scale. The modes simply change the starting and ending note of each scale within a given key. The Major scale in any key is called the Ionian Mode, and in the case of the C major scale it means you start on the note C and the scale follows Do-Re-Me etc. from there. Other modes simply start the scale on a different note. So the Dorian Mode begins on the note D in the C scale and proceeds up the scale with no sharps or flats until you reach D again as the eighth and final note. Modes are used to change the flavor of music within a given key but can be used in all keys. As an example, melodies written in the key of C but in the Dorian mode tend to have a Celtic feel. I have to think that Frye certainly would know this; so his use of the word ‘Mode’, to my way of thinking, must apply in the same way when dealing with literary genres.

This is a rich and interesting topic that needs more discussion.

A nice observation from Peter Yan:

Frye used the musical term mode to describe and order the character’s power in relation to us readers; and how these modes change over time, giving us, in the first chapter of Anatomy of Criticism, how a genuine historical method should work in literature.

What is curious is that the ultimate myth/genre for Frye was the Quest Romance, which he assigned the key signature of C, the key which all keys can be translated into, and the key which all modes musical take off from. The Quest Romance myth is the mode which includes all the other myths in its epic form.

Some very interesting comments from Michael Sinding:

Many thanks for this information, Bob, fascinating as always.

Re: the Circle of Fifths. I’m only going by the Wikipedia article, and I don’t know if I’m saying anything new here, but beyond the relations of harmony and discord in the Circle, it’s also worth noting the important of progression, resolution and mood in both the Circle and the Anatomy’s theory of myths.

The article says: “To the ear, the sequence of fourths gives an impression of settling, or resolution. (see cadence)… [T]he tonic is considered the end of the line towards which a chord progression derived from the circle of fifths progresses.” Also, progression-resolution in the Circle seems to be often either upwards or downwards.

In Anatomy, myths are defined by certain resolutions and moods. And resolution and mood imply a certain foregoing sequence of elements.

Examples:

“The obstacles to the hero’s desire, then, form the action of the comedy, and the overcoming of them the comic resolution” (164).

“In drama, characterization depends on function; what a character is follows from what he has to do in the play. Dramatic function in its turn depends on the structure of the play; the character has certain things to do because the play has such and such a shape. The structure of the play in its turn depends on the category of the play; if it is a comedy, its structure will require a comic resolution and a prevailing comic mood” (171-72).

In response to Michael Sinding’s Comment:

I think Frye never wrote anything extensively on jazz. He gets a good bit of mileage out of the observation that Eliot’s Sweeney Agonistes pulses with a kind of jazz syncopation, repeating that observation three or four times. And there are scattered references to jazz here and there. Here are some:

From Diaries: “It snowed frantically all day, and I sat around wishing the chair in my office was more comfortable, wishing I didn’t have to read that goddamned Edgar book again, wishing I didn’t have to go to the Senior Dinner, wishing I could get started at my book and the hell with all this bloody niggling, wishing the college weren’t getting into such a rah-rah Joe College state, and so on. Regarding this last, Ken Maclean [MacLean] made the very interesting suggestion that Canada was having a post-war Jazz age of its own. It missed, very largely, the 1920 one, but now that we’re getting the post-war children, a lot of prosperity, and a tendency to make the Americans do the responsible jobs, along with a certain backlog of “progressive” education, we seem to be starting where the Americans have left off. (27 March 1952)

In his “Letters in Canada” reviews for 1957 there’s a reference to a poem by a jazz saxophonist. In the same column for 1959 we get this: “John Heath’s Aphrodite is a posthumous collection of poems by a writer who was killed in Korea at the age of thirty four. There is a foreword by Henry Kreisel, who is apparently the editor of the collection. The effect of these poems is like that of a good jazz pianist, who treats his piano purely as an instrument of percussion, whose rhythm has little variety but whose harmonies are striking and ingenious. There is a group of poems in quatrains, split in two by the syntax, where most of the protective grease of articles and conjunctions is removed and subject, predicate, object, grind on each other and throw out metaphorical sparks.”

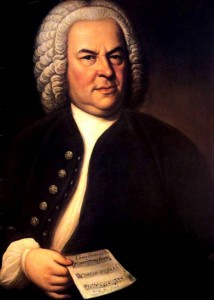

“Thank God for Bach and Mozart, anyway. They are a sort of common denominator in music,—the two you can’t argue about. Beethoven, Chopin, Wagner—they give you an interpretation of music which you can accept or not as you like. But Bach and Mozart give you music, not an attitude toward it. If a man tells me that Beethoven or Brahms leaves him cold, I can still talk with him. But if he calls Bach dull and Mozart trivial I can’t, not so much because I think he is a fool as because his idea of music is so remote from mine that we have nothing in common” (The Correspondence of Northrop Frye and Helen Kemp 1:43.)

About Bach, Frye writes the day after his twentieth birthday: “I have shelved the Temperamental Clavichord for a week or so in favor of the Three-Part Inventions. I have owned them for years and never realized it. The ones I am going after now are those in E minor, A major, B-flat major and C minor—four of the loveliest little pieces I know. You should look at the B minor fugue in Book One of the W.T.C. [Well-Tempered Clavier] too. It’s the longest of them all and covers the whole nineteenth century” (ibid. 41)

“Music was the great area of emotional and imaginative discovery for me” (Interview with Deanne Bogdan, see below)

* * *

The video posted Saturday night of Glenn Gould performing Bach’s “Aria” inspired me to track down some of Frye’s references to the Goldberg Variations.

From Frye’s diary entry of 25 March 1949:

[O]ff to the Forum, where I had a most delightful surprise: Lew [Lou Morris] had bought a lot of dusty old music on spec, & in it were two volumes constituting a complete Bischoff Bach. I need hardly say how I felt the rest of the day, with the Brother Capriccio, the Goldberg Variations, the Sonatas, the French Overture & the A minor Fugue all falling into my lap at once. I must find out what a fair price on it would be.

From Frye’s Notebook 38, par. 46:

In music there’s something profound about the working up of a dramatic narrative structure, rising to an analytic climax in the slow movement, & then a finale that gives the initial impression of comic anticlimax. Mozart’s G m quintet [String Quintet in G minor (1787), op. 516]. In Beethoven’s 4th piano concerto [G minor, op. 58] the tetralogy ending in satyr-play structure is clearer. The reason for it in music is easier to see in the classic variation form, where the dramatic climax is usually penultimate & the very last one a ‘let-down’ (Goldberg & Diabelli). The variation form is not only cyclic but explicitly circumferential, & has to deny narrative advance. (Northrop Frye’s Notebooks for “Anatomy of Criticism” 144)

From Frye’s Notebook 31, par. 36:

The numbers from 28 to 34 are the chief sparagmos numbers. 28 & 29 are lunar & Chaucerian, & V [A Vision] is a kind of lunatic (in the strict sense) Chaucerian (see ref. to Chaucer above [par. 29]) arrangement of what Jung would call psychological types. 30 & 31 are solar & recall the sons of Egypt [Blake’s Book of Urizen, pl. 28, ll. 8–10]. 32 & 33 bring us to the points of the compass & the recurrent Goldberg–Diabelli variation form (counting the theme in G) in music. (Northrop Frye’s Notebooks on Romance 102)

From Frye’s “Wallace Stevens and the Variation Form”:

The long meditative theoretical poems written in a blank tercet form, Notes toward a Supreme Fiction, The Auroras of Autumn, An Ordinary Evening in New Haven, The Pure Good of Theory, are all divided into sections of the same length. An Ordinary Evening has thirty-one sections of six tercets each; the Supreme Fiction, three parts of ten sections each, thirty sections in all, each of seven tercets; and similarly with the others. This curious formal symmetry, which cannot be an accident, also reminds us of the classical variation form in which each variation has the same periodic structure and harmonic sequence. Even the numbers that often turn up remind us of the thirty Goldberg variations, the thirty-three Diabelli waltz variations, and so on. (Spiritus Mundi 276)