httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-_Mr4d_ixSI

Maria Callas sings “D’amor sull’ali rosee” — on the rosy wings of love — from Il trovatore

On this date in 1853 Verdi’s Il trovatore premiered in Rome.

John Ayre in his biography describes a stopover in Rome during Frye’s 1937 visit to Italy, including an opportunity to take in a Verdi opera:

After the exhilarating taste of Tuscany, Frye was thoroughly dismayed. “History of Roman art: bastard Etruscan, bastard Greek, stolen Greek, bastard Oriental, bastard Northern Italian, bastard copies of bastard Greek, bastard Dutch, and various kinds of eclectic bastardy.” In viewing the “junk piles” — the Thermae, the Vatican, the Laterine — he caught a glimmer in the development of Greek sculpture but most everything disappointed. Even what was good was diminished by irritants. The Vatican obsessively plastered fig leaves on nude sculpture. An Italian mania for “restoring” friezes had even spread to the supposedly inviolable Sistine Chapel. There was opportunity, however, of seeing a more enticing contemporary side of Rome — in its opera and ballet — but on the pretext of disliking Verdi, Frye passed up the chance to see a production of Rigoletto. Although he was still suffering a degree of intolerance (Beethoven good, Verdi bad), there was undeniable considerations of money and his still insistent desire to keep working on Blake. (136)

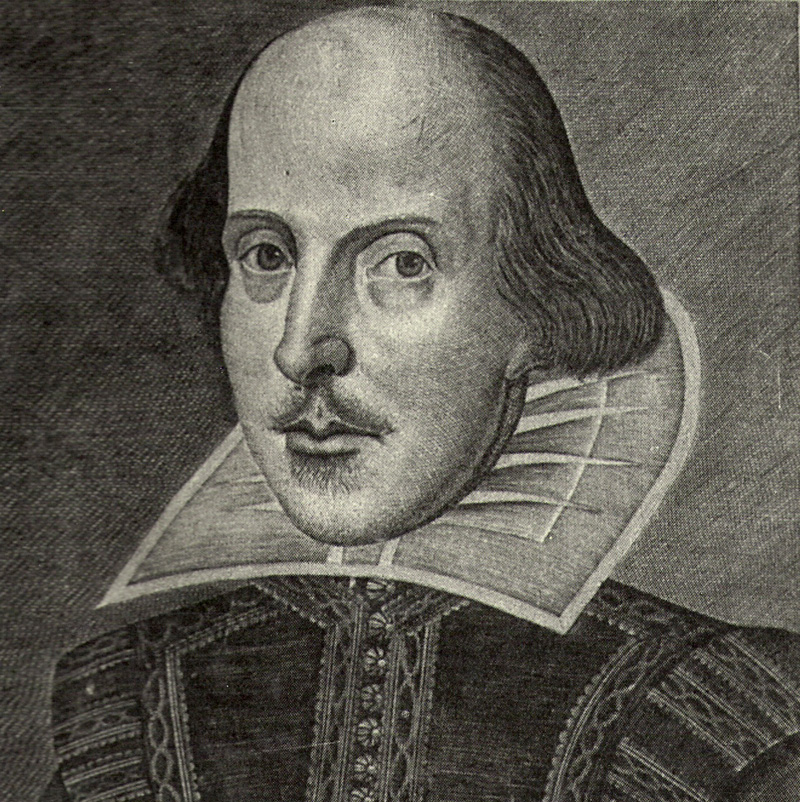

Frye on Shakespeare and opera in A Natural Perspective:

The only place where the tradition of Shakespearean romantic comedy has survived with any theatrical success, as we should expect, is opera. As long as we have Mozart or Verdi or Sullivan to listen to, we can tolerate identical twins and lost heirs and love potions and folk tales; we can even stand a fairy queen if she is under two hundred pounds. And when we look for the most striking modern parallels to Twelfth Night or The Tempest, we think first of all of Figaro and The Magic Flute. (25)