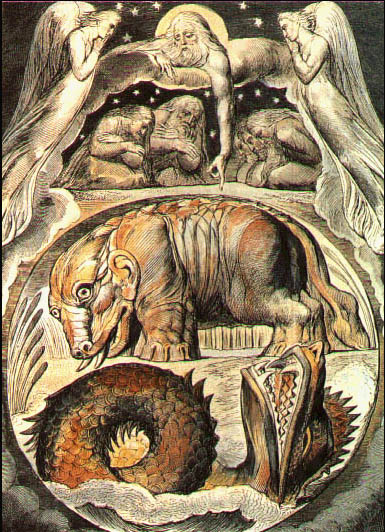

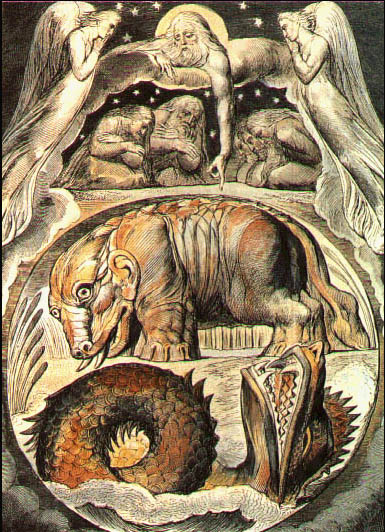

Blake's Behemoth and Leviathan

The complete Religious Knowledge class notes can be found in the Robert D. Denham library at the link above right.

Lecture 13. January 13, 1948

Ritual embodies the ceremonial aspects of the law. The teaching of Jesus is a commentary on the law. He transforms the action to the understanding of the action; that is, myth explains the ritual. In the conception of ritual you act according to the law. In this aspect, sin is a positive act of breaking the law. But for the Gospel, law is the foundation of the human act, not the super–structure. Sin is the failure to transmute the law into human life. All theories of law, justice and judgment are expressed by Jesus in spiritual terms. The Gospel is not a new law.

The law supposes a judge and a person as prisoner. The Last Judgment is usually seen as God “up there” with the people below as sheep and goats. But the sheep and goats are not human, and Jesus does not judge; he casts out devils, and the swine go over the cliff into the “deep,” which is the Hebrew word “tome,” meaning nothingness. The arena of the Last Judgment is the human soul. God enters into the human soul and with His help we cast out the goats, the devils within us,

The apocalypse of personality is God’s descent into the human soul. The Gospel does not bring peace, but a sword. It discriminates and divides. It brings the principle of absolute separation of good and bad in the world. The sheep are the pure, those who have used their talents. The bad are those who have not used their talents, but have buried them.

The myth of the Gospel is the explanation of ceremonial cleanliness. The white sheep are separated from the black goats, the light from the dark, the human from the monstrous. The image to sum up Jesus is the act of casting out devils, the forgiveness of sin. The power of God descending into the human soul to cast out evil even as Jesus descended into the human and fallen world to cast out devils. It happens in man. It is the descent of divine power into man. You cannot make a sheep out of a goat. The sheep is a sheep no matter if it has strayed and been lost. Jesus will find the lost sheep.

Sin is the negative act which fundamentally does not exist since all action is positive and good. The driving out of goats is driving “nothing” out to achieve the complete reality of unfallen man. I know this sounds like a riddle, but play with it for a while . . . .

If casting out devils is the symbol of Jesus’ activity, then we see the relation between prophet and hero more clearly. The prophet is the observer, the watcher, the interpreter of the hero’s action. For the hero or king, what is the heroic act?

Fundamentally, it is the destruction of the powers of darkness. The Gospel tells you the spiritual aspect of the physical act. The religious experience is crystallized in the dragon-killing myth.

The Saviour withdraws man from the dragon so that he can see it is not alive after all. The fairy tale of St. George and the dragon, or the Perseus and Andromache legend, are not just “stories.” St. George is the symbol of the sun, of life, hence his colour is red. The dragon and the old man are the same; winter, waste, sterility. In medieval drama the old king is dressed up inside the dragon. In most variations of this story there is a sinister old woman to balance off the young daughter. In the same way, Perseus has to kill Medusa before he can get cracking on the dragon.

Continue reading →