Lecture 3. October 14, 1947

There is a historical background to the Bible, but what is important is the imaginative ordering of the events.

Assyria destroyed the Northern Kingdom of Israel in 715 B.C. David and Solomon illustrate a brief interval of prosperity. The Kingdom of Judea struggled on longer because Assyria (Nineveh) was destroyed. The Chaldeans come into prominence with the Babylonian captivity. The Jews in Babylon kept their own religion, literature, pedigree. The fall of Jerusalem consolidated them spiritually and nationally.

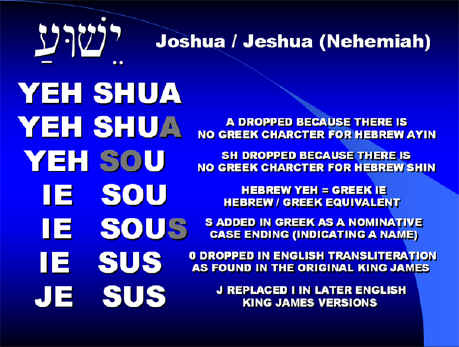

Then came the Medes and Persians, especially the latter, which took over. The Persian Empire was organized under Cyrus, who became the pattern of the Great King. He had a different policy and let the Jews keep their religious traditions and allowed them to return. Nehemiah describes the rebuilding of Jerusalem. Cyrus cleaned up on Croesus and got all of Asia Minor. Darius I was the great organizer and Xerxes carried on the conquest of Greece. The Persian Empire was destroyed by Alexander in the 4th century B.C. The Greeks enter oriental history in migratory droves. The Philistines were Aryan and closely related to the Greeks. For example, Goliath is described as “gigantic.”

At the time of Alexander’s empire, Palestine was ruled by Selecus and Egypt by Ptolemy. These dynasties became absorbed into the country; Selcia became Syria. The tolerant policy was succeeded by attempts to force the Jews to abandon their religion.

At the time of the Maccabean rebellion, the third brother, Julius, was the field commander, and his success was consolidated by Simon. This independence gave them a small period of prosperity because the Romans had not penetrated that far. The rebellion lived on; people looked for a Messiah to deliver them. This was not very long before Jesus’ time. The Maccabean period saw the consolidation of Jewish literature, and the patriotic party of the Pharisees was formed.

The Romans expanded under Pompey. Octavius became the first emperor and Jesus was born during his reign. The Romans became more intolerant; they couldn’t stand the Jews and, therefore, the Christians. In 71 A.D. Titus wiped out Jerusalem and Hadrian completed the process that made the Jews a wandering people. They embarked on a new Babylonian captivity in which Babylon is the whole world.

We must see that the history of the Bible is a mental life, like a child’s memory. Other events become superimposed upon another. For example, for the Hebrews, the Egyptian and the Babylonia captivity become one. Jerusalem is a squalid little town; its magnificence is in the mind.

History is not important, but the imaginative pattern is. The Jews are an oppressed people; therefore their imaginative pattern is greater. The Celtic imagination, for example, creates gigantic heroes, magic, enchantment, a super-nation idea to compensate for being oppressed. This leads to imaginative literature. In the USA, you get a historical sense of fact. What persists are not tall tales, like Paul Bunyan stories, but stories about Washington and Lincoln. America is a successful nation and therefore needs no compensating imaginative history.