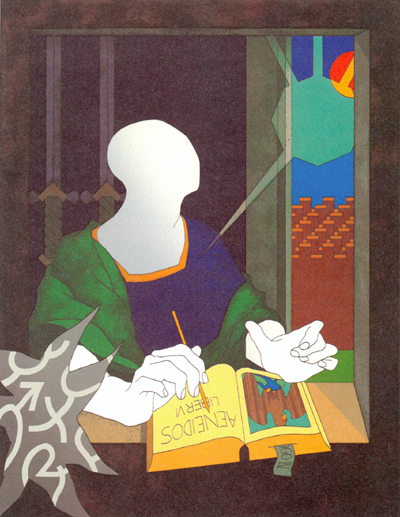

Frye, of course, pilfered the word “anagogy” from Dante, where it’s the highest or spiritual level of meaning. The anagogical meaning of the verse in Psalm 144, which Dante uses to illustrate his four levels, is, he says, “the leave taking of the blessed soul from the slavery of this corruption to the freedom of eternal glory.” In his notebooks for the Anatomy Frye writes that in the anagogic habit of mind “we recognize oneness rather than a unity of varieties,” which is another version of Joe’s point about radical metaphor: identification. It’s true that in writing about anagogy Frye often sounds like a shaman or a symbolist poet. At the anagogic level, he says, for example, “Nature is now inside the mind of an infinite man who builds his cities out of the Milky Way.” Such prose might tempt us to exclaim with Pound, “Anagogical? Hell’s bells, ‘nobody’ knows what THAT is.” Some of the reviewers of the Anatomy poked fun at such explanations. Robert Martin Adams wrote, “I do not, by any means, think it wrong to believe in ‘the whole of nature as the content of an infinite and eternal body which, if not human, is closer to being human than to being inanimate’; but I think it wrong to make such a belief prerequisite to the understanding of literature. My own conviction is that the world rests on the back of a very large tortoise.”

“Anagogy” comes from the Greek, meaning “mystical” or “elevation” (literally “a leading up”). As a medieval level of interpretation, it signified ultimate truth, belonging outside both space and time. In the Convivio Dante refers to it as “beyond the senses” and as concerned with “higher matters belonging to eternal glory.” Aquinas had defined the “anagogical sense” in similar terms (Summa Theologica, pt. 1, Q1, art. 10).

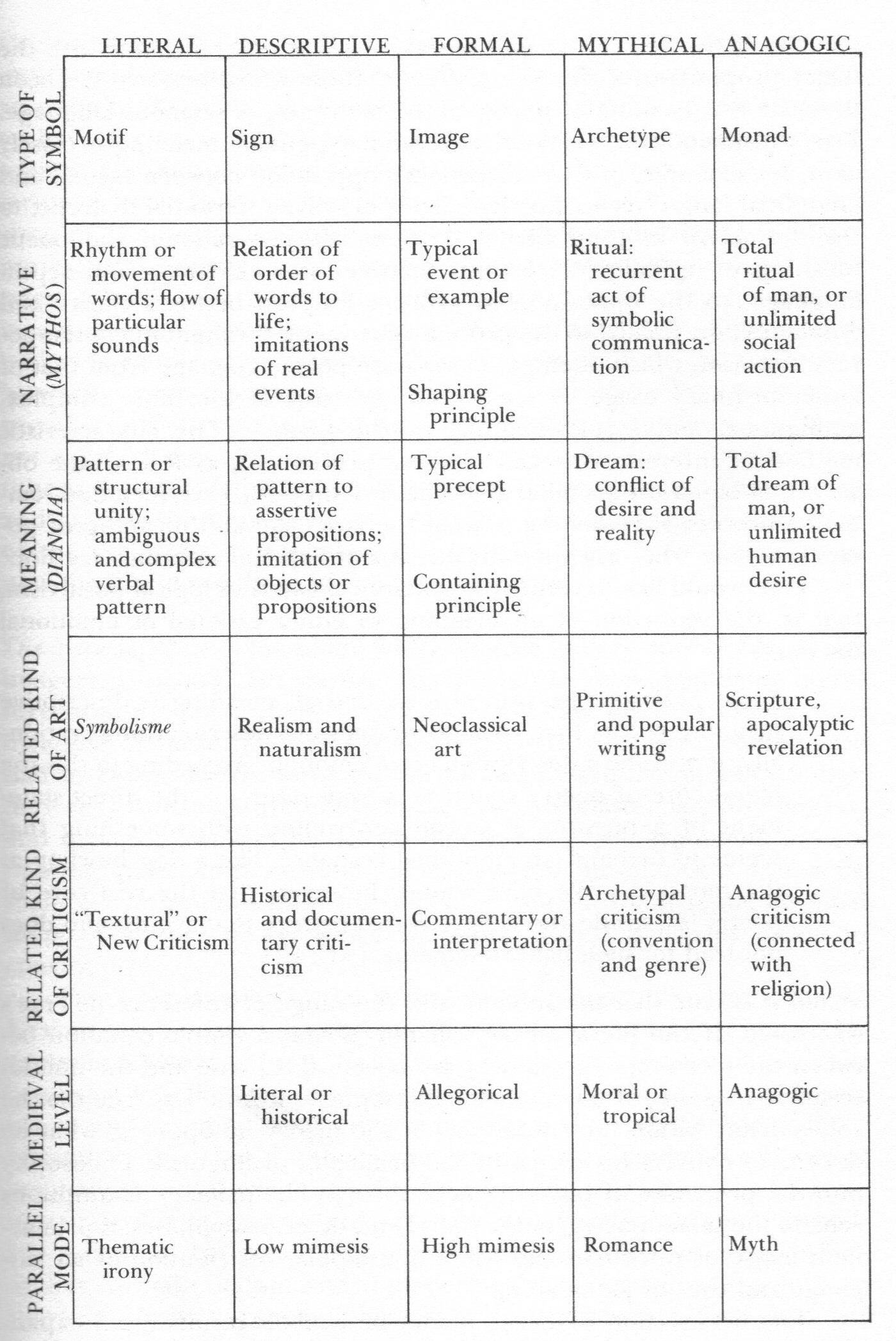

As the final phase of symbolism, Frye introduces us to anagogy in the Second Essay of the Anatomy, but then he more or less drops it, Essays Three and Four descending from the fourth level (mythical and archetypal). The last half of Frye’s career, however, is devoted to the dialectic of Word and Spirit, which is to say, to anagogy.