Michael Sinding responding to the responses to his original post:

Thanks for responses, all. I’ve got a couple more responses to your responses, but let me start with this.

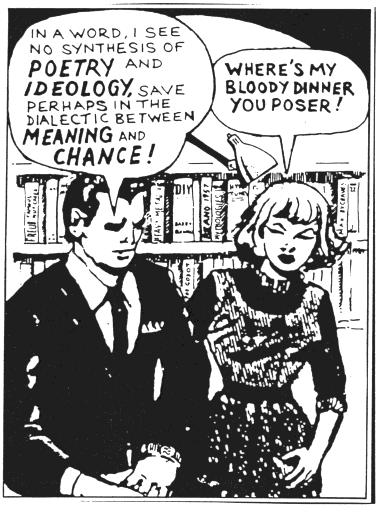

I am sympathetic to the frustration at the current landscape and how it arose, and the regret at what was lost. But I think the frustration can lead to an over-stark picture of the landscape and the people in it, and I think that is counter-productive.

Let me explain my motivation for this view. Since we’re talking about Frye, I think what’s most important to preserving and developing Frye’s ideas is to get them back into circulation, which means getting them back into the scholarly conversation. To do that, we need to see him in a relation to the current landscape that is not simply contradiction, and for that we need a richer picture of it, what it’s talking about and how, its pros as well as its cons, how it’s contributed new perspectives on important topics. Once we’ve got that, then we can develop his ideas in some kind of dialogue with other theories and thinkers. I’m talking about a genuine dialogue, of course, not twisting Frye out of shape to fit a trend, or sneaking him in the back door while currying favour with the Powers. No theory should be swallowed whole or taken up uncritically (bricolage should be the norm), and the conversation should be geared towards improving our understanding of literature and culture (not theory wars).

But if instead we frame the situation just as a disastrous fall from a golden age of Frye, the natural response is to lament the fall, deplore the current situation, wish for some kind of miraculous return in the future. Miraculous, because there’s no foreseeable way for it to happen. To squeeze the metaphor a little further, we need some kind of detailed map of the landscape in order to move in it at all, never mind get through or beyond it—and you can’t get that with a huge brush that paints it all the same way all at once.

That’s why Bérubé’s view from the other side is a helpful corrective: the new paradigm was partly an understandable reaction to an existing entrenched paradigm that similarly dominated scholarship and teaching: literature as Timeless Transcendent Truths, unsullied by the world. I’ve read enough pre-1970s criticism to know he’s got a point, and that it has its very fair share of oversimplification, caricature, and distortion too. So I never had a strong sense of great loss after the revolution, though I couldn’t understand why some people were so gung-ho about it and so un-gung-ho about Frye. (By the way, I had the impression that the revolution was more against New Criticism and Structuralism, and Frye got lumped in with both.)

As I indicated, I don’t wholly agree with any of the critics I mentioned, so I wouldn’t hold them up as ideal models to follow. But that’s not the point. Some authors are not worth the trouble, but with most, I can see past the things I disagree with or dislike to see what’s valuable about them. Same goes for Bakhtin, in fact: he’s repetitive, and he can be sweeping: his monologic/ dialogic distinction is exaggerated, as is his praise of carnival. Nor do I agree with everything about Frye. But Bakhtin and Frye and some of the others are intelligent enough that I prefer to give them the benefit of the doubt and make an effort to see the potential in their writings.

So, no doubt it’s a matter of taste, but I find Greenblatt interesting. Going by “The Improvisation of Power” (from Renaissance Self-Fashioning) in my New Historicism Reader, I find him far more readable than some of the other big names, I don’t find him unduly jargony, and I think he’s got some important ideas. I do find his assumptions about psychology, society, and history quite limiting, though. The attitude of suspicion towards the human mind and culture and what they claim for themselves, suspicion that it’s really all about power and self-interest and nothing else, is too absolute. A skeptical attitude towards self-serving pieties is in order, of course, but when it becomes knee-jerk and never seriously questions itself, it becomes unrealistic. This tendency seems to go far beyond Greenblatt (compare Moretti). Maybe there’s a myth behind it. I don’t know the Said book you mention, Joe, I’ll keep an eye out for it. Maybe I’ll say more about him later. Frye’s remarks are fascinating, as always. But I wonder if anyone else can really do this kind of thing? Not just because it’s so dazzling, but also there doesn’t seem much method in it. “Follow the archetypes.” How? (Maybe more context would explain.)

I notice too that the responses offer criticisms that are often ad hominem—e.g. about the psychology of the revolution, e.g. how it appealed to what’s worst in the academic character, etc. Such arguments are I think essentially unfair, because they’re purely speculative and basically unanswerable. Isn’t such invention of obnoxious motives similar to what we’ve been complaining about in some ideological criticism? Moreover, they can hardly be accurate for everyone in all of these schools. Surely many critics dealing with race, class, gender, ideology, etc. are motivated by genuine social concern, not simply superiority and entitlement. I know enough of them, profs & students, to know this is so. Finally, ad hominem criticisms miss the point because they turn the focus away from the ideas, and it is far more important to deal with the ideas, rather than whatever personal motives and dynamics may be imputed to those who hold them. And it should be a basic principle that in dealing with any approach or school, we deal with the best representatives of it and the best arguments for it, not just any hack job that can be trotted out or invented.

Dealing directly with the ideas can be difficult. As has been said before, Frye’s theories and those that followed are in many ways divergent. If we can use Thomas Kuhn’s over-used idea of paradigms and paradigm shifts for the humanities as well as the history of science, as I have been doing, then the revolution in literary theory was a paradigm shift. (It would be more accurate to say there is a cluster of related paradigms, but I’m speaking in general terms.) And it is much easier to work within a paradigm than to try to change it, or to use some previous paradigm, or to create or use some alternative paradigm. In a sense, this is not fair. Why should people who want to study and teach literature suffer for not buying into a certain paradigm? But there it is. I suppose any field of study always has some paradigm, or a handful of them, and you have to deal with it as you find it. And to once again flatter the cup as half full, we can also see this as an opportunity. There are signs that people are hungry for new ideas. If you have to work harder to budge an entrenched paradigm, the rewards are also potentially greater. And paradigms in the humanities, being looser than those in the sciences, are also more amenable to combination with one another.