Our technical problems have been resolved. All our links –including our Comments links — are now functioning again. Be sure therefore to check out all of Bob Denham’s post earlier today on Archetype.

Our technical problems have been resolved. All our links –including our Comments links — are now functioning again. Be sure therefore to check out all of Bob Denham’s post earlier today on Archetype.

Further to Bob’s post earlier today:

Some more Frye on ghosts, from “Henry James and the Comedy of the Occult”:

Such a story as The Sacred Fount brings the relation of reality and realism into sharp confrontation: either there is some hidden reality that the narrator’s fantasies point to, however vaguely and inaccurately, or there is no discernible reason for setting them forth at all. This principle, which runs through all of James’s work, gives the occult stories a particular significance. A ghostly world challenges us with the existence of a reality beyond realism which still may not be identifiable as real.

He turned once again to his ghost story [The Sense of the Past] just before he died, because in its fantasy he saw the reality he had sought as an artist, whereas the realism in the social manners of his time had left him with a sense of total illusion.

Our McMaster Library server seems once again to be struggling a bit today, so we apologize for any inconvenience. The posts are fine except the ones that are split by the “read the rest of this entry” caption.

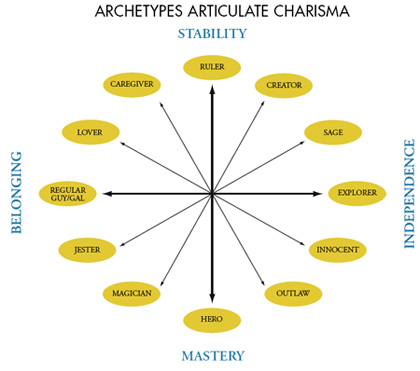

Reading Bob’s post on archetype reminds me how readily I have over the years slipped into referring to just about every verbal phenomenon in Frye as an “archeype” of some sort. I have done so on the principle –which (as Bob also notes) Frye himself acknowledges — that he is an “archetypal critic” in the sense that archetype refers to a recurring pattern of signfication. This seems consisent with Frye’s critical nomenclature generally: the dialectic at work in all of his criticism means that certain terms seem inevitably to expand their reference. For scholars of my generation, for example, the key terms to understanding Frye seem invariably to be “myth,” “metaphor,” and “archetype.” Without an expansive understanding of those words (but also with a very specific understanding that they possess immanent and not transcendental reference), we’d hardly know where to begin at all.

Ghosts

Several of my plans have come smack up against a theory of Bardo, & I can’t help wondering if I don’t need at least a literary theory of ghosts, if not of the whole supernatural. I must start with the vampire theme in Wuthering Heights & see if I can attach it to my floating notions about the echo & the preservation of identity in DM [Daisy Miller], & of the returning ghost in Senecan revenge plays as neurotic, blocked & bound to a pattern of recurrence. The ghost theme in Eliot’s Waste Land (water-nymphs recalling the bodiless souls of Purgatory) winds up with a quotation from the Spanish Tragedy [ll. 266 ff., 432]. Also the Kurtz business, Kurtz being, like Heathcliffe, a “lost violent” soul [The Hollow Men, l. 15–16]. (Northrop Frye’s Notebooks for “Anatomy of Criticism,” CW 23, 222)

Angels

If I had been out on the hills of Bethlehem on the night of the birth of Christ, with the angels singing to the shepherds, I think that I should not have heard any angels singing. The reason why I think so is that I do not hear them now, and there is no reason to suppose that they have stopped. (The Critical Path, 114)

History tells the reader what he would have seen if he’d been present, say, at the assassination of Caesar. But what the Gospels tell us is rather something like this: if you had been present on the hills of Bethlehem in the year nothing, you might not have heard a chorus of angels. But what you would have seen and heard would have missed the whole point of what was actually going on. Thus, the antitypes of history and of prophecy as we have them in the gospel and the apocalypse give you not what you would have seen and heard, or what I would have seen and heard, but what was actually going on which we don’t have the spiritual vision to reach to. (“Kerygma,” in Northrop Frye’s Notebooks and Lectures on the Bible and Other Religious Texts, CW 13, 588)

Responding the Clayton Chrusch:

Frye uses the word “archetype” in different contexts for different purposes. Peter Yan reminds us that Frye called himself a “terminological buccaneer,” and Frye was forever taking over his critical language from other writers. The obvious example is his borrowing mythos, ethos, dianoia, melos, lexis, and opsis from Aristotle’s account of the qualitative parts of dramatic tragedy. In Frye these words hardly resemble at all the meanings that the literal‑minded Aristotle assigned them in the Poetics. Frye redefines them and greatly expands their meaning for his own purposes. In this respect Frye is no different from any other critic. It often takes considerable digging to discover what critics mean by this or that term. A great deal of ink has been spilt in the effort to speculate on what Plato meant by mimesis (certainly different from what Aristotle meant by the term), and to what Aristotle meant by katharsis, Longinus by ekstasis, Sidney by “figuring forth,” Dryden by “nature,” Pope by “wit,” Keats by “Negative Capability,” and so on.

The word “archetype” was perhaps an unfortunate choice because of its association with Jung. Thus, David Richter is led to call Frye a psychoanalytic critic because, like Jung, he used the word “archetype.” Frye read a good deal of Jung, but his appropriation of the word archetype antedates most of what he read in Jung. In reading around in the eighteenth‑century as preparation for writing Fearful Symmetry, he stumbled on the conception of archetype in The Minstrel by James Beattie (the writer mentioned by Peter Yan). No one would have ever guessed that a footnote in a relatively obscure poem by an obscure poet (and moral philosopher) would have been the source of Frye’s conception of the archetype, given many obvious possibilities from Plato’s “forms” on, and we might think Frye to be engaging in a bit of leg‑pulling here were it not for his more extensive discussion of his debt to Beattie’s footnote in “Criticism, Visible and Invisible.,” where he writes:

It is true that I call the elements of literary structure myths, because they are myths; it is true that I call the elements of imagery archetypes, because I want a word which suggests something that changes its context but not its essence. James Beattie, in The Minstrel, says of the poet’s activity:

From Nature’s beauties, variously compared

And variously combined, he learns to frame

Those forms of bright perfection

and adds a footnote to the last phrase: “General ideas of excellence, the immediate archetypes of sublime imitation, both in painting and in poetry.” It was natural for an eighteenth-century poet to think of poetic images as reflecting “general ideas of excellence”; it is natural for a twentieth-century critic to think of them as reflecting the same images in other poems. But I think of the term as indigenous to criticism, not as transferred from Neoplatonic philosophy or Jungian psychology. However, I would not fight for a word, and I hold to no “method” of criticism beyond assuming that the structure and imagery of literature are central considerations of criticism. Nor, I think, does my practical criticism illustrate the use of a patented critical method of my own, different in kind from the approaches of other critics. (“The Critical Path” and Other Writings on Critical Theory 1963–1975, 154–5)

1942:

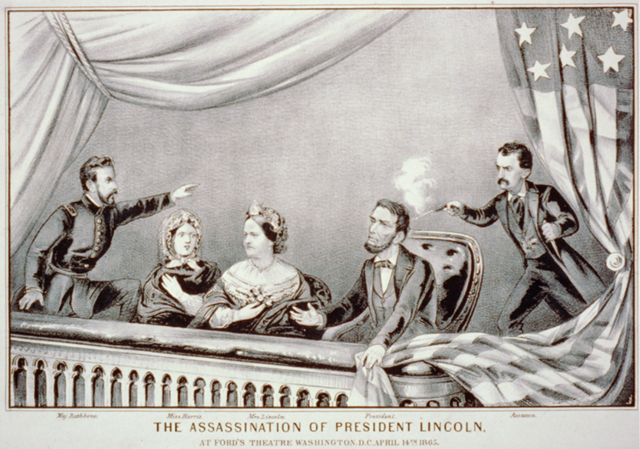

[135] Another S.C.R. [Senior Common Room] one: “they always assassinate the wrong man.”

To Clayton Chrusch on “archetype“:

Frye explaining “archetype” from “Criticism, Visible and Invisible”, The Stubborn Structure:

It is true that I call the elements of imagery archetypes, because I want a word which suggest something that changes its context but not its essence. James Beattie, in ‘The Ministrel’ [poem]…adds a footnote to the last phrase: “General ideas of excellence, the immediate archetypes of sublime imitation, both in painting and in poetry”… I think of the term [archetype] as indigenous to criticism, not as transferred from Neoplatonic philosophy or Jungian psychology. However, I would not fight for a word, and I hold to no “method” of criticism beyond assuming that the structure and imagery of literature are central considerations of criticism.

To Jonathan Allan on “theory“:

As Frye said, the present revolution in criticism must exhaust itself, before the subject can be coordinated again. Too many contemporary theorists dismiss Frye because they want to fight: Marxist Crit, Feminism, Post-Structuralism are militant criticisms which bag whatever targets they try to hit; and when the game is short, they turn their target to literature. Frye’s criticism sees literature as the language of love. Kuhn was right in a way that may have surprised him: if every age produces a paradigm which shifts, then Kuhn’s Paradigm Shift is itself a paradigm which has shifted, and the direction is back to what Frye said all along: knowledge has continuity and repetition. If only the warring schools of criticism would drop their swords.

Answering Russell’s response to my earlier post:

I guess it’s about getting the emphasis right, Russell. To say, as Frye does, that literature is “primarily” centripetal is not to say that it is exclusively centripetal. Frye himself regularly makes the point Greenblatt does in Hamlet in Purgatory: that an understanding of the external “referents” in any given work of literature can only deepen our appreciation of it. However, that’s about where agreement between them ends. Frye’s reading scenario is usually laid out something like this: as readers we are confronted with a work of literature with lots of hard words to be looked up and unfamiliar allusions to be traced back to their source, not to mention a contemporary intellectual milieu to be absorbed. And, of course, it’s a good thing we make the necessary effort to do that; it is certainly an integral part of literary scholarship, as Frye invariably points out. But once we have done all of that, we are still confronted with a work of literature that must be interpreted as such because, as Frye says in The Educated Imagination, literature does not reflect reality, it swallows it. And, as he says in Anatomy, once an ideology is taken into a work of literature, it is no longer ideological in reference, it is literary.

Both of the Shakespeare plays you cite, Hamlet and The Taming of the Shrew, provide excellent opportunities to demonstrate how this works. While it is true, for example, that our appreciation of the afterlife misery of Hamlet’s father’s ghost is enhanced by an understanding of the theological conceptions of the afterlife at the time, it’s pretty clear that no audience of Hamlet requires anything approaching a scholarly knowledge of such a thing. The archetype of the dread surrounding death is more than sufficient to communicate to us what is happening at the elemental level of understanding. Death is terrifying, the afterlife a nausea-inducing mystery. “To be or not to be…” Nuff said.

The same goes with The Taming of the Shrew. We don’t, as you say, have to live in a “ideal world” to see that the normative misogyny of the world of the play is ugly and absurd. The play itself shows us that! One of the things that makes Taming of the Shrew remarkable — and, of course, entirely consistent with the canon as a whole — is its pronounced metaliterary perspective. In this case, it mostly takes the form (like A Midsummer Night’s Dream) of a dramatically superfluous fifth act. That is to say, the standard New Comedy plot is long since resolved by the time of the wedding banquet where Katherine gives her notorious speech in which she entreats the women present to submit themselves to their husbands, even to the point of exhorting them to “place your hands beneath your husband’s foot.” But this little pantomime is no more than that: it’s a fully self-aware show that Petruchio and Katherine are putting on for the benefit (or is it at the expense?) of their less imaginitively adept peers. We in the audience proper know better. We know that by this point Katherine and Petruchio have successfully (albeit with a tremendous amount of rough and tumble) negotiated together a world of play where nothing is quite what it seems — where the sun may be the moon or vice versa, and an old man encountered on the road to Padua may be mistaken for a “young budding virgin” — or, more accurately (and much more interestingly) be pretended to be mistaken for one. Do I also have to mention the Christopher Sly framing device that gives the play an absolutely explicit metaliterary dimension? The ironies of the fifth act are so rich and evocative that any attempt to reduce them to a flatly declarative ideological intent, however good those intentions, is demonstrably contrary to the inner workings of the play itself.

Here’s my point. I know that many can and do dispute such a reading of the play. However, it is also undeniable that this reading is at least possible with reference to what goes on within the play and without reference to any ideological anxiety beyond it. We are, of course, not compelled to see the play in these terms; but we are free to do so on very good authority (that is, the centripetal focus of the play as such), and that is always Frye’s point. All of our limits, when it comes to literature, are self-imposed. As Merv Nicholson might say, “what makes Frye different” is the articulation of the possibility that we might voluntarily recognize those self-imposed limitations and stroll happily and unencumbered right past them.

Responding to Michael Happy:

You say, Michael, “you don’t need to believe in ghosts to appreciate Hamlet.” This reminds me of something at the MLA in 1993. Walter Benn Michaels made the comment that “we no longer believe in ghosts,” then interrupted himself to say that he had just read in a newsmagazine that a majority of Americans believed in supernatural entities. He gestured around the room; “We don’t believe in ghosts,” he corrected himself.

To pursue the discussion a bit further: yes, literature creates a hypothetical world where there are ghosts, whether we “believe” in them or not. But on the other hand, Stephen Greenblatt, in Hamlet in Purgatory, shows how our reading of Hamlet is enriched by some knowledge of contemporary debates about what happens after you die. Why does the ghost of old Hamlet walk at night? What does it mean to die “Unhousel’d, disappointed, unanel’d”?

I think the point Bogdan is making, where she differs from Frye, is that literature always retains some element of reference, a centrifugal element, and that in teaching it you cannot ignore that element. Her example is to question Frye’s assertion that “the preposterous sexual ideology” of The Taming of the Shrew is “never taken very seriously.” Perhaps in an ideal world it wouldn’t be. Which is not to say that, not living in an ideal world, one shouldn’t teach the text or perform it, only to acknowledge that in certain contexts it is going to be interpreted in part in the context of what it has to say about gender relations.

One more example. Frye comments about Measure for Measure that it is simply a romantic comedy “where the chief magical device used is the bed trick instead of enchanted forests or identical twins.” This is one of those startling places where Frye just seems to me to miss something crucial. The reason that Measure for Measure has been seen as a “problem” is that there is something about the tone of it, from beginning to end, that is not really in the spirit of Shakespearean comedy. I think that here, and in the comment on Taming of the Shrew, it is Frye’s acute sense of the conventions at work that leads him to a conclusion at odds with the experience of many readers and spectators. Because although it is hypothetical, although it is centripetal, literature still does say things.

Perhaps, Michael, you see me grasping confidently for the greased pig! (By the way, your last sentence is very Bloomian, featuring both anxiety and struggle!!). But I will agree with you so far as to say that the greatness of The Tempest or Measure for Measure or Hamlet is not a function of what they reveal about Renaissance ideology. And I don’t want to become the contrarian of this blog, so I will write something more positive for my next post.