Russell Perkin’s last post has raised some important questions. He expresses his sympathy with Deanne Bogdan’s realization “that literary experience could be negative as well as positive.” One of my questions would be: who decides what is negative or what is positive? On what basis do we decide that something is a positive or a negative experience. To pretend that one can answer that question without difficulty is the stance of ideological criticism, the posture of cultural studies, which assumes that the answer is more or less straightforward. Maybe it seems straightforward in certain instances, but even here I would emphasize the “seems.” It is the indispensable function of the liberal arts and their criticism that they require us to suspend any final decision that is based on an ideological assumption, left or right, feminist or patriarchal.

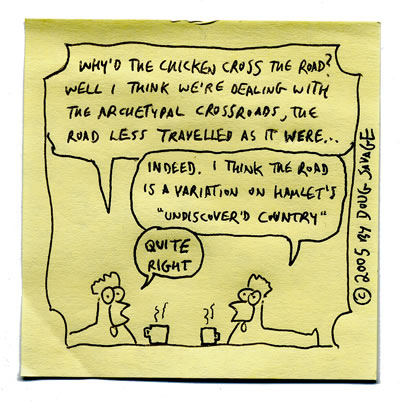

The compelling reasons for a defense of free speech, so eloquently made by Milton, and so lucidly and unassailably by Mill, speak to the very essence of the imaginative vision embodied in literature. The response to literature is not monolithic, but inevitably various–it demands and allows for a great variety of response–and this is inherent in its imaginative and therefore hypothetical nature. It means that a work may strike one person as sexist, and another as liberating and feminist–something that is evident even in the ongoing debates among feminists since the movement began.

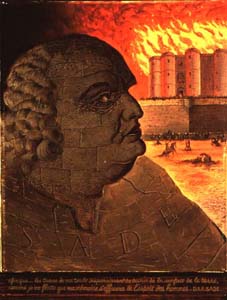

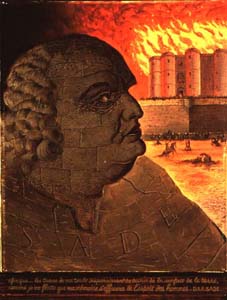

One aspect of a work, experienced as negative to one person, may be experienced as positive by another. Sade is an excellent example; his work is, in my mind, unquestionably a part of a liberal culture and the arts, and yet I can see that much of it is hard not to judge as repugnant, and many would see his work as irredeemably obscene, misogynistic and dangerous to read, and therefore would seek to suppress it. And yet some of the most visionary poets of the last two centuries regard Sade as a prophet, not of misogyny, but of emancipation.

Let us ponder where the question raised by Bogdan can lead: it is very tempting to assume that we have the truth, and we know what is offensive and what is not: what is feminist and anti-feminist, what is racist and what isn’t, what is wrong and what is right. But where did we get the assumptions for any such conviction at all: that this is grotesque, and this the norm or goal? Presumably from some “myth to live by,” some vision embodied in religion, literature, philosophy, and the arts and science, the basis of liberal culture, the core of which is an informing vision that is available, not only in the ideas and emotions evoked in the experience of the arts, but in their underlying structures, their under-thought, their poetic and mythological underpinnings.

The concern about the bad or good experience that literature might afford is definitely not something that Frye ignored, not at all. Frye had no objections to feminist criticism; he had an objection to feminist criticism, or Marxist criticism, or minority criticism, or majority criticism, for that matter, becoming the basis, the arbiter of criticism.

The question Russell raises is a good one, and the beginnings of an answer, I think, is in the very passage he quotes from Frye:

Anything that emerges from the total experience of criticism to form part of a liberal education becomes, by virtue of that fact, part of the emancipated and humane community of culture, whatever its original reference. Thus liberal education liberates the works of culture themselves as well as the mind they educate.

This is Frye’s point about the nature of a liberal education and their core, the arts: art and literature, because they demand an imaginative response, are submitted to a different kind of judgment, which demands both engagement and detachment, not moral or ideological judgment.

Unfortunately, once you insist that a certain literary work can only evoke a “negative experience,” it is not hard to take the next step: to refuse to entertain any reading of that work except as an example of what one ought not to think or say. And then you have subordinated criticism to an ideological agenda, to a matter of belief. This is, unfortunately, what has taken place in many areas of literary criticism and scholarship today.

amson very graciously provided a

amson very graciously provided a