As we’ve been following the laissez-faire thread for some time, it’s nice to end up seeing it as part of a larger social and literary pattern.

From “Varieties of Eighteenth Century Sensibility”:

The feeling of an intensely social view of literature within the Augustan trend has to be qualified by an interpenetration of social and individual factors that were there from the beginning. The base of operations in Locke’s Essay is the individual human being, not the socially constructed human being: Locke’s hero stands detached from history, collecting sense impressions and clear and distinct ideas. Nobody could be less solipsistic than Locke, but we may notice the overtures in Spectator 413, referring to “that Great Modern Discovery . . . that Light and Colours . . . are only Ideas in the Mind.” The author is speaking of Locke on secondary qualities. All Berkeley had to do with this modern discovery was to deny the distinction between primary and secondary qualities to arrive at this purely subjective idealist position of esse est percipi, “to be is to be perceived.” If we feel convinced, as Johnson was, that things still have a being apart from our perception of them, that, for Berkeley, is because they are ideas in the mind of God. It is fortunate both the permanence of the world and for Berkeley’s argument that God, according to the Psalmist, neither slumbers not sleeps [Psalm 21:4]. But Berkeley indicates clearly the isolated individual at the centre of Augustan society who interpenetrates with that society.

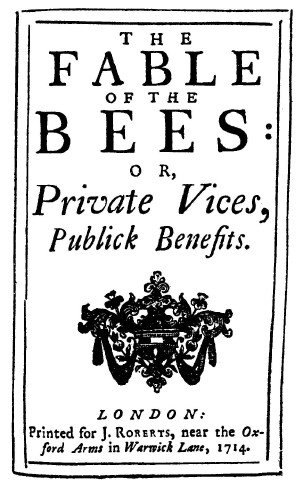

The same sense of interpenetration comes into economic contexts. In the intensely laissez-faire climate of eighteenth-century capitalism there is little emphasis on what the anarchist Kropotkin called mutual aid: even more than the nineteenth century, this was the age of the work ethic, the industrious apprentice, and the entrepreneur: the age, in other words, of Benjamin Franklin. A laissez-faire economy is essentially an amoral one: this fact is the basis of Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees, with its axiom of “Private Vices, Publick Benefits.” The howls of outrage that greeted Mandeville’s book are a little surprising: it looks as though the age was committed to the ethos of capitalism, but had not realized the intensity of its commitment. (CW 17, 29-30)