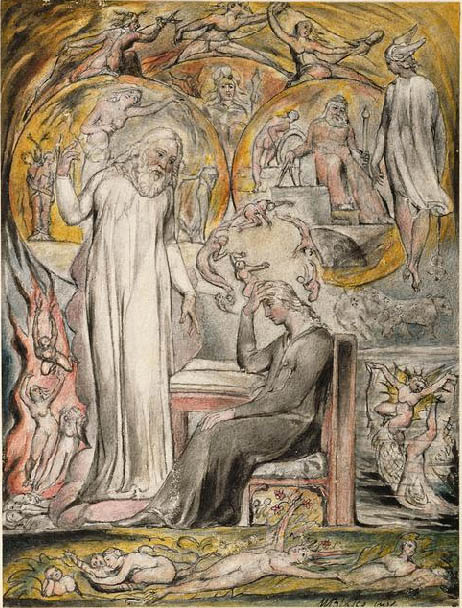

Giovanni di Paulo, Dante and Beatrice Leaving Heaven, ca. 1465

Responding to Bob Denham’s post

I like and agree with all that you say about Frye and the Bible, Bob, but feel there are a few things missing, like typology and prophecy. To say that Frye is looking at the Bible from the point of view of a literary critic is correct but seems to me to be a far too cold and detached statement–Frye as a scientific anatomist.

In Fearful Symmetry Frye is learning from Blake and teaching us that the Bible is a complete book of vision. With my philosophical and theological frinds I have enjoyed many heated and lively conversations, but we always seem to reach an impass when we come to the word “vision”. Their favorite word is “insight”, the eureka moment, and this seems to be pretty well an established occurrence in consciousness, and the title of a major work by that other great Canadian thinker, Bernard Lonergan. This “insight” is the basis for an alternative to faculty psychology, dealing with the soul and its attributes, which has now been abandoned in the wake of scholasticism. The nearest scholasticism comes to Blake’s “vision” is with the word “emanation”, as in Aquinas’ “intelligible emanations”, our participation through the act of “insight” in the light or mind of God. Understanding is what we achieve each time we have an “insight”. The historian Herbert Butterfield states that the rise of modern science outshines everything since the birth of Christianity. Modern science comes with the Enlightment and philosophers like Paul Ricoeur, Gadamer, Eric Voegelin and Leo Strauss are now trying to dismantle its stranglehold and go beyond it.

In this sense, Frye does not approach the Bible as a scientist or literary critic but, instead, as a prophet and poet. What emerges from Fearful Symmetry is Blake’s universal cry that we find at the opening of his poem Milton: “Would to God that all the Lord’s people were Prophets.” Numbers XI. ch. 29 v.

To go beyond either/or, Frye approaches the Bible both as a literary critic where he suspends value judgements but also as a prophet like Jeremiah where he uses value judgments to tear down and to build up. [See Jean O’Grady’s brilliant article “Re-valuing Value“.] The key to prophecy is typology, the Medieval approach to the Bible, displayed to us splendidly in Dante’s Divine Comedy. In “Paradiso” Canto 6, Justinian is the only speaker, and here we deal with the Law; canto 10, the Circle of the Sun, the Circle of the Sages, we deal with Wisdom; canto 17 deals with Prophecy. His great, great grandfather tells Dante must go back to earth and assume the mantle of the prophet and poet. Armed with the phases of revelation: Law, Wisdom, Prophecy, Etc., Dant must construct for us The Divine Comedy, which is nothing less than a recreation of the Bible.

Frye’s engagement with the Bible brought about a fundamental change in him as it did in Dante, and it was this change into prophet and poet that was necessary before he could present us with his lasting emanation, The Collected Works of Northrop Frye, which we must learn to read as the Bible for our time.