Responding to Quote of the Day

Thanks for this, Mike. The quotation and the article in full made me think of Frye’s references to the lamentable disappearance of the old Honour course at the University of Toronto. It would be interesting to know more about that. Perhaps our Southern Pez-dispenser can cough something up for us.

I certainly identified with what the guy was saying about the frayed sense of purpose in the classroom when the discipline itself is so incoherent and uncertain. Interesting he uses the term “secondary considerations” in the quote you provide: what he means of course is what Frye calls secondary concerns. Just a coincidence?

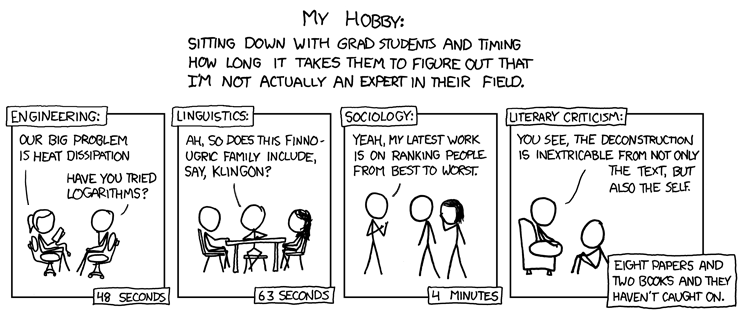

Even in my grad class . . . though maybe “even” isn’t the right adverb, given that, at least in my department, there is a concerted effort to train any spontaneous responses to literature out of our students long before they are in any danger of attending a graduate seminar . . .

I was going to say how predictable it is now that the immediate response by students to an image in a novel or a textual detail or a set of such images or details is to explain or rationalize them by referring, in one way or another, to the world outside the work. (This has always been the case but it is now actively encouraged.) And this centrifugal impulse is usually accompanied by a critical attitude that undermines in a knowing and dismissive, even contemptuous way the author and the work. This is called “critical thinking,” much touted in the last decade or so as one of the great skills that humanities students can bring to their employers. The training that goes into it is analogous to those educational kid’s books which present pictures in which the details are out of place or wrong and the child is supposed to point out all the errors. Please point out, class, the relevant errors in Keat’s “Ode to a Nightingale” . . . Yes, exactly: the Ruth image is indeed a perfect example of the patriarchal aestheticization of exploited female labor . . .

I think part of the explanation for why such a critical approach has caught on is that it is so damn easy to do: it spares the students and more importantly the professors from having to really think critically about what they are reading, since the technique is to short-circuit from the beginning the imaginative energy of the text, the electrical linking, if you like, of one image to another, within the text or in other works of literature.

Let us now criticize famous writers seems to be the general idea: or rather let us “critique” or “problematize” them. Or my favorite: let us “resist” them. The books are no longer being read: they are being resisted, as if a poem were trying to put one over on you, like some sleazy salesman trying to sell you a highly overpriced and shoddy vacuum cleaner.

Reading as resistance: which really means resisting reading. Resist, don’t fall for that image, don’t pick up that theme–you have no idea where it might have been . . . Remember: your soul is in peril of eternal incorrectness.