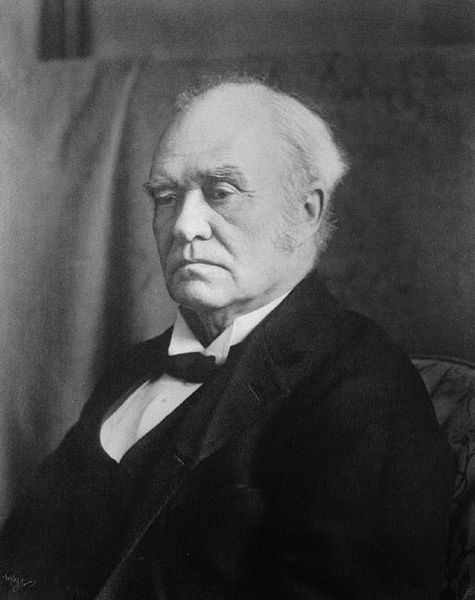

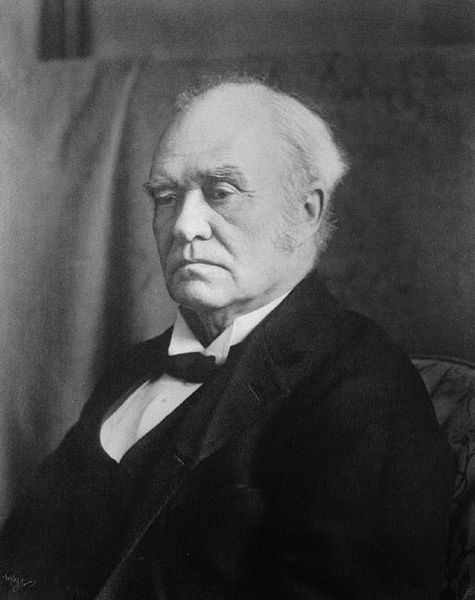

Today is the birthday of our sixth and shortest-serving Prime Minister (68 days in 1896), Sir Charles Tupper (1821-1915). He was a baronet, and one of the eight of our first nine prime ministers (Sir John MacDonald serving two non-consecutive terms) to be knighted: our second, Alexander McKenzie was the exception, and our ninth, Sir Robert Borden, was the last. The title reveals our close political and cultural ties with the Empire in the early years of the nation, right down to the First World War.

Here’s Frye in a 1984 interview with David Cayley for the CBC Radio program “Richard Cartwright and the Roots of Canadian Conservatism”:

Frye: Nobody coming from the planet Mars and studying Canadian history would believe that Canadians retained loyalty to the British government through a century of total ineptness, where the British had always preferred American interests to Canadian ones and made it clear that they would have more respect for Canada if it were no longer a colony. But the problem from the Canadian view is, What else are we going to do? Where else are we going to find our identity in the continuity of that tradition?

*

Frye: I tend to think more and more as I get older that the only social identity that’s really worth preserving is a cultural identity. And Canada seems to me to have achieved that, so I don’t join with other people in lamenting the loss of a political identity.

*

Frye: I think that culture has a different sort of rhythm from political and economic developments which tend to centralization, and that the centralization process has gone so far in the great world powers that the conception of the nation is really obsolete now. What we have instead among the great powers are enormous consolidations of social units, and cultural tendencies are tendencies in a decentralizing direction. If you talk about American literature, for example, you have to add up Mississippi literature and New England literature, Mid-Western, Californian, and so on. And the theme of cultural identity immediately transfers you to a postnational setting.

*

Frye: Regional culture, as I see it, is a culture in which the writer has struck roots in his immediate environment. There’s always something vegetable about the creative imagination, and you can’t transplant James Joyce and Alice Munro to the middle of Brazil and expect them to product the same kind of works. They’d become different cultural vegetables in that case. With the poets of the [Sir] Charles G.D. Roberts generation, there was really very little sense of region. The Confederation Ode of Roberts is inspired by a map, it is not inspired by people. I think we’re in a period of history now where we’re just beginning to realize that, as one book says, “small is beautiful,” that is, there is a tendency to decentralize and a feeling that the great world powers have grown to the point where they’re not really workable any more. They’re become increasingly dinosauric in their functioning. And with that, the sense of a cultural or regional identity begins to emerge as a genuinely human identity. (CW 24, 273-5)