httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2tTDiZZYCAs

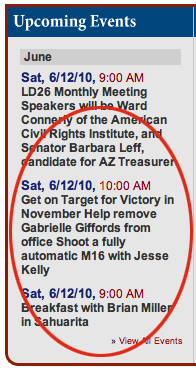

Gabrielle Griffords warns Sarah Palin about the “consequences” of putting people in “gun sights”

Clearly, the one thing that would put an end to all hope for genuine social advance in our society would be the growth of conservative violence: the effort, with the aid of a hysterical police force, to trample down all protest into that state of uneasy quiescence under terror which is what George Wallace means by law and order. As the recent Chicago fracas showed, there can be no real doubt that such counter-violence would be much more directed at radicals, even of the most peaceful kind, than at criminals. (“The Ethics of Change,” CW 7, 349)

All the social nightmares of our day seem to focus on some unending and inescapable form of mob rule. The most permanent kind of mob rule is not anarchy, nor is it the dictatorship that regularizes anarchy, nor even the imposed police state depicted by Orwell. It is rather the self–policing state, the society incapable of formulating an articulate criticism of itself and of developing a will to act in its light. This is a condition that we are closer to, on this continent, than we are to dictatorship. In such a society the conception of progress would reappear as a donkey’s carrot, as the new freedom we shall have as soon as some regrettable temporary necessity is out of the way. No one would notice that the necessities never come to an end, because the communications media would have destroyed the memory. (The Modern Century, CW 11, 24)

Once a society renounces violence as a means of resolving its differences, controversy and discussion provide the only means of social advance. Where we have two separating camps of commitment, advance through discussion is paralysed, because all arguments become personal. The argument is seen only as a rationalization of one side, and its proponent is merely identified as a radical or a reactionary, a Communist or an Uncle Tom. (I do not see much force in this last epithet, by the way: Uncle Tom, who was flogged to death for sticking by his principles, seems to me quite an impressive example of non-violent resistance.) The continuing of the paralysis of discussion, in breaking up meetings, shouting down unpopular speakers, and the like, congeals into a mood of anticipatory violence. (“The Ethics of Change,” CW 7, 351)

In all societies there is a built-in tendency to anti-intellectualism. Sometimes this is maintained by a state-enforced dogma, as it is in the vulgar Marxism of the Soviet Union or the still more vulgar version of the Moslem religion enforced in Iran. Sometimes, as in North America, it is simply part of the human resistance to maturity, and to the responsibilities that maturity brings, the instinct to stay safe and protected by the crowd, to shrink from anything that would expand and realize one’s potential. It is this element in society that makes all education, wherever carried on, what I just called a militant enterprise, a constant warfare. The really dangerous battlefront is not the one against ignorance, because ignorance is to some degree curable. It is the battlefront against prejudice and malice, the attitude of people who cannot stand the thought of a fully realized humanity, of human life without the hysteria and panic that controls every moment of their own lives. Words like “elitism” become for such people bogey words used to describe those who try to take their education seriously. At the heart of such social nihilism, this drive to mob rule and lynch law that every society has in some measure, is the resistance to authority. (“Language as the Home of Human Life,” CW 7, 588)

As long as man’s fear of life is deeper than his fear of death, there will always be a tendency for society to degenerate into a mob, moved only by prejudice and hysteria and hatred of the individual. According to Christianity God himself was a victim of such a mob. We are not in a cosy white and black melodrama: we ourselves are involved in crime and corruption. There are millions of people who admire what we have, and fully intend to get it, but don’t particularly admire what we are. Their pressures and others may increase the fears of our own society, and people are not at their best when frightened. What one “does” with a university education in the modern world is to return to one’s community and devote one’s life to trying to build up a real society out of it and to fight the mob spirit wherever it is. Creating such a society is the main meaning and purpose of human life, and your specialized preparation for it begins here. (“Speech at a Freshman Welcome,” CW 7 280)

A group of individuals, who retain the power and desire of genuine communication, forms a society or community. An aggregate of egos is a mob. A mob can only respond to reflex and cliché; it can only express itself, directly or through a spokesman, in reflex and cliché. A mob always implies some object of resentment, and political leaders who speak for the mob aspect of their society develop a special kind of tantrum style, a style constructed almost entirely out of unexamined clichés. Examples may be heard in the United Nations every day. What is disturbing about the prevalence of bad language in our society is that bad language, if it is the only idiom habitually at command, is really mob language.

What is high style? This is one of the oldest questions in rhetoric: it would almost be possible to translate the title of Longinus’ treatise, Peri Hypsous, written in the second century, by this question. As Longinus recognized, the question has two answers, one for literature and one for speech, or rhetoric. In literature it is correct to translate Longinus’ title as “On the Sublime,” and discuss the great passages in Shakespeare or Milton. In rhetoric high style is something else: something more like the voice of the individual reminding us of our real selves, and of our duty as members of a society and not of a mob. To go at once to the highest example of high style, the sentences of the Sermon on the Mount have nothing in them of the speech-maker’s art: they seem to be coming from inside ourselves, as though the soul itself were remembering what it had been told so long ago. High style in this sense is ordinary style—it can even be “low” style—but in an exceptional situation. In our society it is heard whenever a speaker, like Lincoln at Gettysburg, is honestly struggling to express what his society, as a society, is trying to be and do. It is even more unmistakably heard, as we should expect, in the voice of an individual facing a mob, or some incarnation of the mob spirit, in the death speeches of Vanzetti and Louis Riel, in the dignity with which a New Orleans mother explained her reasons for sending her white child to an unsegregated school. How, marvelled the reporters, did a woman who left school in grade six learn to talk like the Declaration of Independence? It was the authority of high style in action, moving, not on the middle level of thought, but on the higher level of imagination and social vision. The mob’s version of high style is advertising, the verbal art of prodding the reflexes of the ego, and telling it, in a voice choking with emotion, what our vision of society should inspire us to do: to go instantly down to the store and demand this product, accepting no substitutes. As long as society retains its freedom, such advertising is largely harmless, because everybody knows that it is only a kind of ironic game. As soon as society loses its freedom, mob high style becomes what is usually called propaganda, and the moral effects become much more pernicious. (The Well–Tempered Critic, CW 21, 352–3 )

Continue reading →