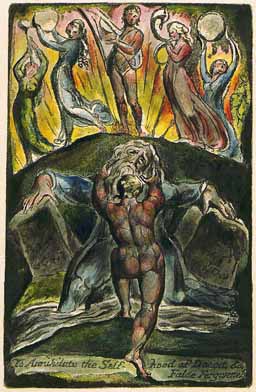

Blake’s “To Annihilate the Self-hood of Deceit,” 1804-1808

Whenever we are tempted to believe that our current economic disparities and injustices are just the way it has to be, Frye in Fearful Symmetry takes on the money economy from a prophetic perspective:

Money to Blake is the cement or cohesive principle of fallen society, and as society consists of tyrants exploiting victims, money can only exist in the two forms of riches and poverty; too much for a few and not enough for the rest. La proprieté, c’est le vol, may be a good epigram, but it is no better than Blake’s definition of money as “the life’s blood of Poor Families,” or his remark that “God made man happy & Rich, but the Subtil made the innocent, Poor.” A money economy is a continuous partial murder of the victim, as poverty keeps many imaginative needs out of reach. Money for those who have it, on the other hand, can belong only to the Selfhood, as it assumes the possibility of happiness through possession, which we have seen is impossible, and hence of being passively or externally stimulated into imagination. An equal distribution, even if practicable, would therefore not affect its status as the root of a evil. Corresponding to the consensus of mediocrities assumed by law and Lockean philosophy, money assumes a dead level of “necessities” (notice the word) as its basis. Art on this theory is high up among the nonessentials; pleasure, in society, tends to collapse very quickly into luxury and affection. (CW 14, 82)

Interesting POV on the “money economy,” but does Frye comment as to what would be a viable alternative?

I waited for a couple of days, Gene, in the hope that someone else would step in — and I’m still hoping they will. It’s a good question and deserves a better response than I can provide, but here goes.

Is “viable alternative” the best way to frame it? That assumes that the current arrangement has some bearing on what we really need. I don’t think Frye believed it does. Our state is fallen. Our arrangements — like the money economy — are likewise fallen. Our genuine “alternatives” are therefore potentially apocalyptic rather than merely “viable.” In order to get it right, we must toss the better part of what we do and what we expect into the trash. It can’t be about possession. It’s got to be about what we can give, most especially to those who are obviously in need. I’m not sure of the reference, but I am sure that Frye at least once articulated the redeemed world Jesus preached as a world where there is nothing to take because everyone is giving. What does the absence of such a world yield? Well, this: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kimberly_Rogers Kimberly Rogers was a single expectant mother on welfare who was harassed to death by the then Conservative government of Ontario because she drew benefits while also taking student loans to go to college. Look, I can’t do justice to the story. Just go read it yourself and see if you can find any way to accept that this precious, fragile life deserved to be snuffed out by those who do not even seem to know what it means to be alive. I am pretty sure what your response will be. Maybe that’s where we start.

Michael, I think you are right that the alternatives are apocalyptic. In Fearful Symmetry, speaking of Milton, Frye writes:

“The greatness of Areopagitica is that it speaks for liberty, not tolerance: it is not a plea of a nervous intellectual who hopes that a brutal majority will at least leave him alone, but a demand for the release of a creative power and a vision of an imaginative culture in which the genius is not an intellectual so much as a prophet and seer. The release of creative genius is the only social problem that matters, for such a release is not the granting of extra privileges to a small class, but the unbinding of a Titan in man who will soon begin to tear down the sun and moon and enter Paradise. The creative impulse in man is God in man; the work of art, or the good book, is an image of God, and to kill it is to put out the perceiving eye of God. God has nothing to do with routine morality and invariable truth: he is a joyous God for whom too much is enough and exuberance beauty, a God who gave every Israelite in the desert three times as much manna as he could possibly eat. No one can really speak for liberty without passing through revolution to apocalypse.”

You cannot extract from these words any kind of systematic doctrine or solution to economic or social problems, but that is because, at least according to Frye, the solution is not systematic.

At last I worked my way back to this topic.

I agree with Clayton that whatever solution there may be will not be systematic. It’s got to appeal to the populace on an elemental level, and can’t be merely a matter of “guilting” people into doing the right thing.

Here’s an interesting quote I derived from I AND THOU when I did a quickie comparison between Buber and Marx:

“Every Thou in the world is by its nature fated to become a thing, or continually re-enter into the condition of things. In objective speech it would be said that every thing in the world, either before or after becoming a thing, is able to appear to an I as its Thou. But objective speech snatches only at a fringe of real life.

The It is the eternal chrysalis, the Thou the eternal butterfly — except that situations do not always follow one another in clear succession, but often there is a happening profoundly twofold, confusedly entangled.”

FYI, here’s the essay proper:

http://arche-arc.blogspot.com/search/label/martin%20buber

My essay’s probably not very charitable toward Marx, but I’m convinced his concept of human nature was much more limited than Buber’s. I’m not sure Buber wrote anything about economics but I’d extrapolate that any “cash nexus,” to use Marx’s term, fits the process Buber describes above, where every “Thou” either becomes an “It” or something that takes part in the process of the “It,” the thing without a “Thou.” That’s just my extrapolation, though.

I mentioned that I felt that human love and art are often capable of breaking down the barriers between people, but that to some extent those barriers generally re-assert themselves in some way. That’s what I think we’re up against with the challenge of “still-not-at-all compassionate conservatism” in this country.

I like what you say Gene. Marx’s solution is systematic, and isn’t a real solution. I think you are right that Marx wants to honor the I-Thou, but by turning it into an economic transaction of love for love, trust for trust, he returns it to the chrysalis, returns it to I-it.

Buber is closer to the truth because he recognizes both the distinctness of chrysalis and butterfly but also their interdependence, and therefore the absurdity of honoring the butterfly by dishonoring the chrysalis.

Blake, I think, has Marx’s moral fire but Buber’s subtlety. Blake recognizes what Buber recognizes, but also extracts the moral truth out of Marx’s half-truth, namely that the butterfly is the fulfillment of the chrysalis. For Blake, it is the butterfly’s problems that are the real problems and the butterfly’s solutions that are the real solutions not because the chrysalis’s problems don’t matter but because the greater includes the lesser.

Only full human and social development is a real solution to any human or social problem. The only way I can get rid of my gut is by becoming an athlete. The only way I can develop a good vocabulary is by reading widely and well. The only way I can be rich is by investing my talents and making them grow. The only way I can get one person to love me is by learning to love everyone. The only way we can raise people from poverty (and obscene wealth) is by transforming society and every individual in it into fully developed human beings.

Agreed, and here’s another quickie comparison: The development you’re addressing might be related to Adler’s idea of “positive compensation.” Whereas “negative compensation” doesn’t really address the problem, as I’m claiming that Marx’s egalitarianism wouldn’t have addressed man’s true nature, the less-well-known “positive” kind affirms the genuine potential latent in every human’s potential.