During most of the summer, I have spent my time reading about love and loss. I have delved into literary theory, theology, psychoanalysis, and literature. In a recent article – “Can We Read the Book of Love?” in PMLA – Richard Terdiman writes: “people love being in love, and when they are they talk and write about it with an expansive intensity.” I am struck by a persistent desire as readers to read about love. Romance novels continue to be the largest portion of book sales in the United States, and during a recession romance novels increase in sales. Indeed, “we love being in love.”

Roland Barthes in A Lover’s Discourse observes that “to try to write love is to confront the muck of language: that region where love is both too much and too little, excessive (by the limitless expansion of the ego, by emotive submersion) and impoverished (by the codes on which love diminishes and levels it).” Barthes and Terdiman seem to agree that love and to write about love is to be excessive: both too much and too little.

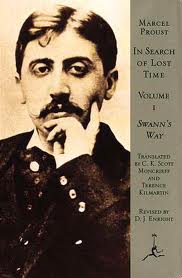

In his recent novel, A Familiar Rain, John Geddes explores the problem of love and loss: the problem being one where we strive to return, always, to a love lost. While reading A Familiar Rain, I was also reading and writing about Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time; more specifically, I was writing about The Fugitive, a book that opens, “Mademoiselle Albertine is gone,” and narrates the loss of Albertine and Marcel’s reactions. In A Familiar Rain, we are presented with a protagonist who falls in love and loses his first love. Throughout the novel, he is researching memory and returning to our memories (at times the novel seems to recall H. G. Wells’ Tono-Bungay). Of course, the novel illustrates the problems of this search for lost time.

The problem with reliving memories, we learn, is that “all of the sorrows and the trauma we usually get over by forgetting, she can still recall. It could torment her. I’m not sure if this is a blessing or a curse.” And indeed, this is precisely the problem with remembering: intrinsic to a memory is not always a positive experience. Memory can force us to long for that which is now lost and yet persistently present because we cannot, we do not, forget. Nowhere is this more true than in the story of love, where “memory is burned into your consciousness.”

In Proust’s Swann’s Way we read:

Many years had elapsed during which nothing of Combray, except what lay in the theatre and the dram of my going to bed there, had any existence for me, when one day in the winter, on my return home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, offered me some tea, and a thing I did not ordinarily take. I declined at first, and then, for no particular reason, changed my mind. She sent for one of those squat, plump little cakes called “petites madeleines,” which look as though they had been moulded in the fluted valve of a scallop shell. And soon, mechanically, dispirited after a dreary day with the prospect of depressing morrow, I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked the morsel of cake. No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shiver ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestions of origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory – this new sensation having had the effect, which love has, of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me, it was me. I had ceased now to feel mediocre, contingent, mortal. Whence could it have come to me, this all-powerful joy? I sensed that it was connected with the taste of tea and the cake, but that it infinitely transcended those savours, could not, indeed, be of the same nature. Where did it come from? What did it mean? How could I seize and apprehend it? (I.60)

The madeleine has become a symbol of memory and being flooded by memories. This is not a negative or a positive, and how we read this passage will vary from reader to reader. In A Familiar Rain there are many “madeleine moments” in which a character sees something that provokes a memory of the past, and often enough, of his first love, Laura.

Abbey stood very close to him, peering over his shoulder as he leafed through the book. He could feel her body next to his and instinctively leaned in toward her basking in her warmth. As he turned a page his heart leapt; there on page seven was Laura’s handwriting where she inscribed Laura Whitaker, SMC. He felt as he if could hardly breath. He was holding in his hand Laura’s favourite book, a book she had held many times and he was looking again at her signature in her distinctive handwriting style as if she had penned it today.

He began to experience an overwhelming sense of guilt, as if Laura was looking down on him at that moment, shocked that he was reveling in the physical closeness of Abby. The room started to spin and he felt lightheaded and nauseous. It seem liked his legs were not able to support him and before he knew it, Abbey had helped him to an oak chair and managed to get him seated.

This moment is a madeleine moment, a small object is able to overwhelm the viewer and he is overcome by memories of things past. Northrop Frye in a brief passage on Proust observes:

If we try to recall our identity from conscious memories of the past, it retreats like a forgotten name, until we give up trying. But sometimes, when our minds are on something else, the movement is reversed: the memory comes out, as it did to Proust, touches the rememberer, and says, in several ways, “here you are.” (CW 29, 330)

These small items provoke wonderful memories and they remind us of who we are and where we belong. A Familiar Rain is an elegy to a lost love, and yet it is also a novel on the infamous madeleine, which has come to symbolize the entire Proustian project. The strangeness of memories and remembering is not the memory itself but rather, as Frye notes, those smaller things that provoke memories. These small objects overwhelm us precisely because love is overwhelming; it is, in the words of Barthes, too much and too little.

“I was wandering the streets of Moncton, thinking how, in the course of time, memory tends to distribute itself between waking life & dream life. Some of my most vivid dream settings have been on Moncton streets. Streets are, of course, a labyrinth symbol, full of Eros: they recapture not past reality but my reality, reality for me. I wish I knew what I meant: something eludes me. Cf. Joyce’s hallucinatory Dublin, the name Dedalus, the Count of Monte Cristo.” (CW 9:166)

Frye on the madeleine in Proust

As a fiction writer Samuel Beckett derives from Proust and Joyce, and his essay on Proust is a good place to start from in examining his own work. This essay puts Proust in a context that is curiously Oriental in its view of personality. “Normal” people, we learn, are driven along through time on a current of habit energy, an energy which, because habitual, is mostly automatic. This energy relates itself to the present by the will, to the past by voluntary or selective memory, to the future by desire and expectation. It is a subjective energy, although it has no consistent or permanent subject, for the ego that desires now can at best only possess later, by which time it is a different ego and wants something else. But an illusion of continuity is kept up by the speed, like a motion picture, and it generates a corresponding objective illusion, where things run along in the expected and habitual form of causality. Some people try to get off this time machine, either because they have more sensitivity or, perhaps, some kind of physical weakness that makes it not an exhilarating joyride but a nightmare of frustration and despair. Among these are artists like Proust, who look behind the surface of the ego, behind voluntary to involuntary memory, behind will and desire to conscious perception. As soon as the subjective motion picture disappears, the objective one disappears too, and we have recurring contacts between a particular moment and a particular object, as in the epiphanies of the madeleine and the phrase in Vinteuil’s music. Here the object, stripped of the habitual and expected response, appears in all the enchanted glow of uniqueness, and the relation of the moment to such an object is a relation of identity. Such a relation, achieved between two human beings, would be love, in contrast to the ego’s pursuit of the object of desire, like Odette or Albertine, which tantalizes precisely because it is never loved. In the relation of identity consciousness has triumphed over time, and destroys the prison of habit with its double illusion stretching forever into past and future. At that moment we may enter what Proust and Beckett agree is the only possible type of paradise, that which has been lost. For the ego only two forms of failure are possible, the failure to possess, which may be tragic, and the failure to communicate, which is normally comic. (CW 29:160)

Dante is within the orbit of the sacred scripture, where God is the creator, but the same principle of reversed movement can be associated with human creativity. Such a reversal occurs at the end of Proust, where an experience of repetition transforms Marcel’s memory of his life into a potential imaginative vision, so that the narrator comes to the beginning of his book at the point where the reader comes to the end of it. Time being irreversible, a return to a starting point, even in a theory of recurrence as naive as Nietzsche’s, can only be a symbol for something else. The past is not returned to; it is recreated, and when time in Proust is found again (_retrouvé_), the return to the beginning is a metaphor for creative repetition. [Joe Adamson’s note: “As Marcel negotiates the uneven paving-stones in the courtyard of the Guermantes mansion, he experiences the same happiness as that which he felt upon tasting the madeleine dipped in tea, described in the opening volume of the work. Inside the mansion, the sound of a spoon knocked against a plate and the feel of a napkin continue to trigger sensations linked to the striking disappearance of doubts about “‘the reality of [his] literary gifts, the reality even of literature.’”]