In a review of 1984 when it first appeared, Frye writes that the real value of the book is that the author

gives us a terrifyingly clear impression of what we don’t want for either ourselves or our children. Mr. Orwell doesn’t tell us what to fight for, but he gives us a terrifyingly clear impression of what we should fight against. And what we should fight against, according to him, is not Russia or China, not Eurasia or Eastasia, but the evil tendencies in our own minds, our own weak and gullible compromises in a contempt of law and a contempt for truth. (CW 10, 143)

What is it exactly if not these evil tendencies, driven by contempt, that have given the Harper Conservatives permission to compromise their consciences, to lie, deceive, break rules and the law, cheat, conceal, refuse to answer questions, de-route all democratic process, and generally engage in vindictive attacks on perceived enemies and malign and smear honest public servants who inconveniently speak the truth? The great psychologist and affect theorist Silvan Tomkins–like Frye, a genius with a grand theory–postulates that at the heart of contempt is a drive auxiliary that acts like an affect and which he calls “dissmell.” Dissmell is clearest in the sneer, the raised upper lip directed at another, as if other people smelled bad and were not fit for human consumption.

Tomkins points out that in a democracy contempt (which is unilateral dissmell combined with anger) is rarely used (Tomkins calls it the most unappealing affect), because it undermines the assumption of equality and solidarity with others. It is however a central affect in authoritarian and hierarchical societies, where dominance and superiority must be communicated by rejecting and distancing “malodorous” others. Contempt, as Tomkins neatly puts it, is the mark of the oppressor.

In contrast, shame is the affect central in democratic societies, because shame does not sunder the interpersonal bridge: it is not unilateral and only functions when there is already an affluence, a closeness and fellow feeling that is impeded in some way but with only an incomplete reduction of enjoyment or interest. Shame implies an identification with others, and a wish to return to the good scene of communion with the other. Contempt, on the other hand, insists on an unbridgeable distance from the other in the first place, so that there is no good scene to return to. There is no identification with the other. It is a very handy affect if you want to lynch someone, or cheat them out of their life’s savings, or if you are just part of an oligarchy that wants to avoid uncomfortable feelings of guilt (moral shame) for the misery that has been inflicted on the rest of the human population.

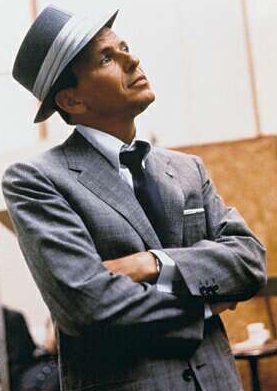

Compare for example, the facial display of Dick Cheney with that of Barack Obama. As far as I know, Cheney’s prominently raised upper lip is not due to any physical paralysis of any kind; it is an expression of dissmell. It is hard to imagine a sneer like Cheney’s coming over the features of someone like Obama. So when you have a leader of a government, Stephen Harper, who treats his own fellow citizens with dissmell it is best to be suspicious and wonder about the fate of our democracy.

But as of yet too many Canadian voters seem inert, immobilized, unconcerned with the erosion of democratic institutions and processes, and it is this very situation the Conservatives count on in a fear campaign directed at everybody’s pocket book. Harper’s government is a perfect example of what Frye calls, in an essay on democracy which I will quote more fully below, a “managerial dictatorship.” Its primary model is a corporation, and thus it is naturally in conflict with democratic principles and processes. The only principles the Conservatives uphold are the rights of Canadians to own unregistered deadly weapons and to pollute the environment in the name of the economy. But, to lift a phrase from Thoreau,“whether we should live like baboons or like men seems a little uncertain.”

In contrast to the current inertia of voters is the famous reversal in the 1993 election when a negative Conservative ad ridiculing Jean Chrétien’s facial paralysis turned the election around on a dime, leaving the Conservatives, by the time the dust had settled, with only two seats in the country. It was an encouraging moment. It was uplifting to know that the voters could say so loudly and clearly that such a mean and ugly attack on a fellow human being and citizen is just not welcome here, thank you very much.

The following paragraph is from an essay Frye wrote in 1950, an essay he wrote for The Varsity, the student newspaper at the University of Toronto. He is not speaking in affective terms, but the antithesis he speaks of is the same:

All governments whatever must be either the expression of the will as a minority holding autonomous power, which is able to impose that will on society as a whole, or the expression of the will of the people as a whole to govern themselves. In the former case there is an antithesis between a ruling class and the ruled classes; in the latter case there is no governing class, but only a group of executives and public servants responsible to society as a whole for what they do. The latter conception is the democratic one. (CW 11, 235)

“Democracy,” he goes on to say, “ is thus essentially the attempt to preserve law and order in society which has superseded the primitive and outmoded idea of ‘rule.’” We now have a government, of course, that seeks the very opposite: to rule as a minority and actively undermine the preservation of law and order in its own house: the House of Commons. Our House, as Michael so rightly puts it. The Conservatives have been found in contempt of parliament, guilty as charged of obstructing parliament and undermining democracy. Consider this paragraph from Frye in the same essay:

Anti-democratic social action, of the kind intolerable to a democracy must necessarily be in the direction of withdrawing information and action from the community as a whole. It is a contradiction in terms for democracy to tolerate a conspiratorial coup d’etat aimed at the restoration of the old idea of a professional ruling class. (236)

I can’t think of a better way of describing the threat that this country faces right now.