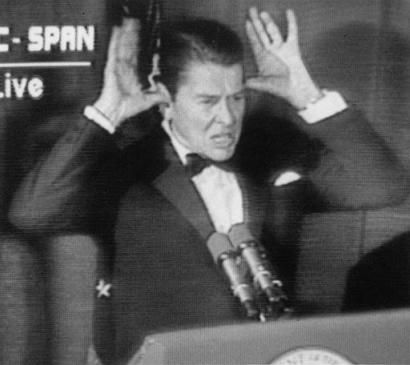

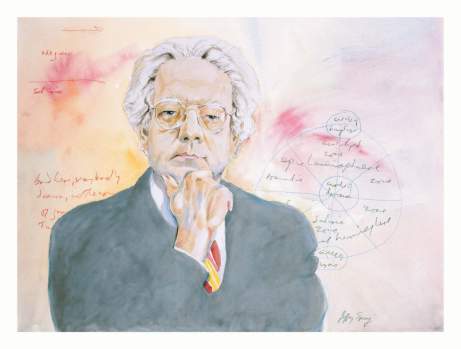

Further to the previous post, here is some cultural studies avant la lettre: Frye on Reagan, the Pope, and “the prison of television.”

[282] Television brings a theatricalizing of the social contract. Reagan may be a cipher as President, but as an actor acting the role of a decisive President in a Grade B movie he’s I suppose acceptable to people who think life is a Grade B movie. The Pope, whose background is also partly theatrical, is on a higher level but the general principle still holds. It goes with reaction, identifying the reality with the facade. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if, just for once, it could be true that Father knows best? Emotional debauch of father-figuring. (Notebook 27)

[492] American civilization has to de-theatricalize itself, I think, from the prison of television. They can’t understand themselves why they admire Reagan and would vote for him again, and yet know that he’s a silly old man with no understanding even of his own policies. They’re really in that Platonic position of staring at the shadows on the wall of a cave. The Pope, again, is another old fool greatly admired because he’s an ex-actor who looks like a holy old man.

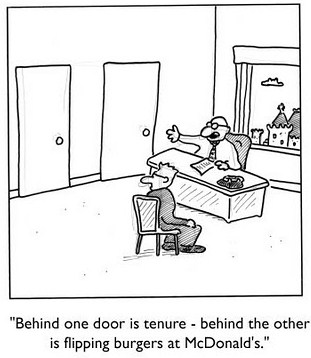

[493] Watching a television panel of journalistic experts discussing the (Bush-Dukakis) election, it seemed to me Plato’s cave again and Plato’s eikasia, or illusion at two removes–show business about show business. All one needs to know about such horseshit is how to circumvent whatever power it has. I’m trying to dredge up something more complex and far-reaching than just the cliché that elections today are decided by images rather than issues–they always were. It’s really an aspect of the icon-idol issue: imagination is the faculty of participation in society, but it should remain in charge, not passively responding to what’s in front of it. Where does idolatry go in my argument? End of Three? (Notebook 44)

[85] Why do Americans continue to cherish Reagan, including millions of Americans who know he’s an ass? I think they’re bored by their own indifference to the world, but can only focus their minds on a boob-tube leader. (Notebook 50)