Several years back I puzzled over the conjunction of Word and Spirit in Frye’s later writing, concluding that they did in effect serve as a great code to his words of power. Here’s an adaptation of what emerged:

Word and Spirit in their capitalized forms appear, as one would expect, throughout his work, and in numerous contexts. In The “Third Book” Notebooks, “Word” is often associated with what Frye calls the Logos vision and “Spirit” with the traditional Holy Spirit. But “Word” and “Spirit” do not appear in Frye’s writing as a dialectical pair until the late 1970s, and before the writing of Words with Power only three times. In one of the notebooks for The Great Code he refers in passing to “pericopes of Word & Spirit” (CW 13, 268), and when he is trying to work the relation between the cycle, which he eventually abandoned, and the axis mundi, which became his primary spatial metaphor, he speculates, in an intriguing entry, that “the up and down mythological universes form a wheel, and the wheel is the cycle of recurrence. In the cyclical vision everything becomes historical, and there is no Other except the social mass. The impulse to plunge into that is strong but premature. Something here eludes me. The answers are in interpenetration and Thou art That, but the real individual is not the illusory series of phantasmal egos in time: it’s the total body of charitable articulation. The assumptions underlying this articulation are Word & Spirit. Probably the crux of the whole book” (CW 13, 327). Here Frye appears to have the answer but does not know what the question is. What are the two things that interpenetrate in this passage, a difficult one to gloss? Thou (the individual) and That (the social mass)? The self and the Other? “Charitable articulation” could be seen as Frye’s final cause. The material cause would then be “Word” in its several senses, the formal cause “Spirit,” and the efficient cause criticism in all of its Frygian permutations: its aphorisms, commentary, schema, imaginative free play, investigations of myth and metaphor, analogical linkages, sober speculations, creative flights of fancy. The word “articulation” reminds us that Frye’s universe is a linguistic one. “I’m glad I’m not concerned with belief,” he says, “but only with trying to understand a language” (CW 13, 303), which is reminiscent of his later statement about not believing in affirmations but only in the verbal formulas he constructs (CW 5, 145). These formulas, he goes on to say, “seem to make sense on their own, & seem to me something more objective than merely getting something said the way I want it said. I hope (but again it’s not faith) that this is the way the Holy Spirit works in me as a writer” (ibid.). Frye consistently focused on finding language to articulate the substance of his vision (spirit), which in turn leads to the end of that vision (charity).

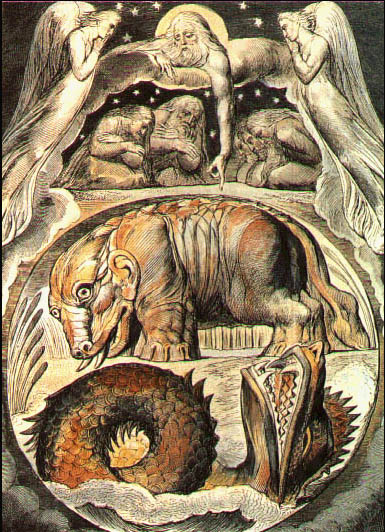

The third instance of “Word and Spirit” occurs in The Great Code itself, where Frye writes that creative doubt of the Nietzschean variety can carry us “beyond the limits of dialectic itself, into the infinite identity of word and spirit that, we are told, rises from the body of death” (227). Words with Power is likewise relatively silent about the pairing of Word and Spirit. In that book Frye does write that “the unity of Word and Spirit in which all consciousness begins and ends” is what constitutes the spiritual self, and he speaks of the “intercommunication” of Word and Spirit (Words with Power, 251). In the Late Notebooks, however, the phrase “Word and Spirit” occurs some fifty-two times, often as “Word and Spirit dialogue” or “Word-Spirit dialogue.” Frye uses “dialogue” here in the sense of dialectic. And the dialectic is between the two major modes in Frye’s thought––the literary mode of the word writ large, or logos as Word, and the religious mode of spiritual vision, or pneuma as Spirit. But dialogue is also a metaphor for the relation between Word and Spirit, or an “intercommunication,” as in the passage just cited. The Word, Frye says in Notebook 27, gives substance to the Spirit. Each sets free the other, and they are united in one substance with the “Other.” That is, Word and Substance interpenetrate (CW 5, 9). “Infiltrate” is another word Frye uses to define the relation (CW 5, 272).