httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7E4S-E2qAX8

The finale of Verdi’s Falstaff.

Joe Adamson’s post about the stages of ascent and descent reminded me of Frye’s Seattle epiphany, which he conceived of as part of a dialectic that occurs along the axis mundi. Here’s an adaptation of something I wrote several years back about this epiphany––what Frye called his Seattle illumination, referred to in an earlier posting, “Frye’s Epiphanies.”

The references to the Seattle epiphany are somewhat cryptic: they center on what Frye calls the passage from oracle to wit. The oracle was one of Frye’s four or five “kernels,” his word for the seeds or distilled essences of more expansive forms. He often refers to the seeds as kernels of Scripture or of concerned prose. The other microcosmic kernels are commandment, parable, and aphorism, and (occasionally) epiphany. Frye sometimes conceives of the kernels as what he calls comminuted forms, fragments that develop into law (from commandment), prophecy (from oracle), wisdom (from aphorism), history or story (from parable), and theophany (from epiphany). There are variations in Frye’s account of the kernels (aphorism is sometimes called proverb, for example, and occasionally pericope and dialogue are called kernels), but those differences are not important for understanding the oracle-wit illumination.

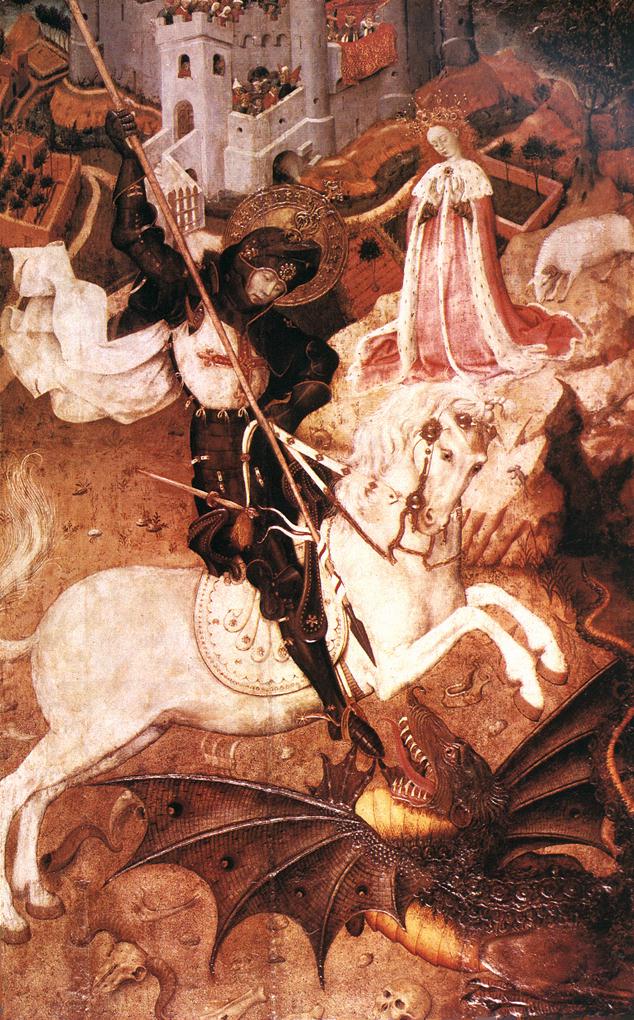

Oracle is almost always for Frye a lower-world kernel. It is linked with thanatos, secrecy, solitude, intoxication, mysterious ciphers, caves, the dialectic of choice and chance, and the descent to the underworld. The locus of the oracle is the point of demonic epiphany, the lower, watery world of chaos and the ironic vision. The central oracular literary moments for Frye include Poe’s Arthur Gordon Pym’s diving for the cipher at the South Pole, the descent to the bottom of the sea in Keats’s Endymion, Odysseus in the cave of Polyphemus, the Igitur episode in Mallarmé’s Coup de Dés, the visit to the cave of Trophonius, and, most importantly, the oracle of the bottle in Rabelais, who was one of Frye’s most admired literary heroes. As for wit, in the context of the Seattle illumination, it is related to laughter, the transformation of recollection into repetition, the breakthrough from irony to myth, the telos of interpenetration that Frye found in the Avatamsaka Sutra, new birth, knowledge of both the future and the self, the recognition of the hero, the fulfillment of prophecy, revelation, and detachment from obsession. The oracular and the witty came together for Frye in the Finale of Verdi’s Falstaff.

Frye calls the Seattle illumination a “breakthrough,” and the experience, whatever it was, appears to have been decisive for him. He was thirty-nine at the time, literally midway through his journey of life. One can say with some confidence that the Seattle epiphany was a revelation to Frye that he need not surrender to what he spoke of as the century’s three A’s: alienation, anxiety, absurdity; that he realized there was a way out of the abyss; that he embraced the view of life as purgatorial; that, in short, he accepted the invitation of the Spirit and the Bride in Revelation 22:17. “The door of death,” Frye writes, “has oracle on one side & wit on the other: when one goes through it one recovers the power of laughter” (“Third Book” Notebooks, 162). And laughter, for Frye, is the “sudden release from the unpleasant” (Notebooks on Romance, 73). Oracles are, of course, ordinarily somber, and wit, in one of its senses, is lighthearted. Pausanius tells us that the ritual of consulting the oracle in the cave of Trophonius was so solemn that the suppliants who emerged were unable to laugh for some time: but they did recover their power to laugh. There is a “porous osmotic wall between the oracular and the funny,” Frye writes in Notebook 27 (Late Notebooks, 1:15). Similarly in Gargantua and Pantagruel, when Panurge and Friar John consult the oracle of the Holy Bottle, there is, if not literal laughter, an intoxicating delight that comes from the oracle’s invitation to drink; and we are told that the questers then “passed through a country full of all delights.” This is why “Rabelais is essential to Dante” (Late Notebooks, 1:15). But laughter here is more than a physical act. It is a metaphor for the sudden spiritual transformation that is captured in the paravritti of Mahayana Buddhism. Paravritti literally means “turning up” or “change,” and according to D.T. Suzuki it corresponds to conversion in religious experience. In the Lankavatara Sutra we are told that in his transcendental state of consciousness the Buddha laughed “the loudest laugh,” and in his marginal annotation of this passage Frye notes that “the laugh expresses a sudden release of Paravritti.”

Continue reading →