Nicholas Graham sent us this email a couple of days ago:

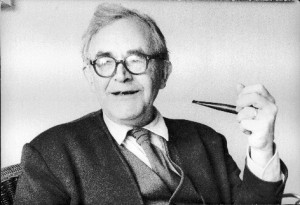

Here is one of the many highlights to be found among Frye’s Dante annotations.

I would like to share it with anyone who is able to throw some light on Frye’s distinctions.

I have asked some of my theologian friends to explain Frye’s distinction between “the Maritains & the Barths”. Also I would like to know a little more about each of the types of visions that Frye presents here.

Maybe you could start an annotations corner on your wounderful blog?

You can see Graham’s transcript of the annotation here. Please have a look, and if you have anything to add, leave us a comment.

The answer to Nick’s question is, yes. We will set up a dedicated space for annotations. We’ll let you know once we get it up and running.,

And, of course, queries of any sort are welcome. We are always glad to post them.

Here are two responses to Graham’s query.

From Bob Denham:

Isn’t the Maritain/Barth distinction simply that Maritain accepted the analogia entis and Barth rejected it. See Barth’s Church Dogmatics, vol. 3, pt..2, trans. Knight et al. (Edinburgh: Clark, 1960), 220. See also Keith L. Johnson, Karl Barth and the Analogia Entis (2010).

I have a brief discussion of Frye and the analogia entis in “Frye and Giordano Bruno,” which has been posted on the Frye blog. In a “General Note: Blake’s Mysticism,” Fearful Symmetry, CW 14:415–16, Frye contrasts Blake’s analogia visionis with “the more orthodox analogies of faith and being.”

Frye’s aligning the four forms of analogia with Dante’s four levels of meaning is a pretty ingenious schematic. Of course Frye’s ultimate commitment is to anagogy, where the principle of identity, as opposed to analogy, operates.

From Michael Dolzani:

My knowledge here is highly limited, despite growing up Catholic; I thought analogia was a girl I went to high school with. However, I think Bob is basically right. The Catholic Maritain accepts the analogia entis and is thus trapped in reason; the Protestant Barth rejects it and manages thereby to open a path to the analogia visionis, to vision, via the Logos. I wonder when these notes were written: this all seems an outbreak of Norrie’s visceral antipathy to Catholicism, which I’ve never really understood.

I know that the Catholic Church of his youth was extremely reactionary, and that he disliked the potential authoritarianism of the neo-Thomist movement, which he saw as parallel to something like Eliot’s Anglo-Catholic insistence on “orthodoxy,” but Catholicism really seems to have been a sore spot. After all, Aquinas may be dryly Scholastic, but I find Augustine’s obsession with sin, damnation, predestination, and the like as repellent as anything in the Inferno. When Benedict recently abolished half of Limbo (the unbaptized infants), there were a lot of articles talking about the historical background; I don’t know if it’s true that where Aquinas said the souls of unbaptized infants were merely denied heaven, Augustine went further and said that they shared to a degree the punishments of the damned–but it sounds like something he’d say.

In short, Norrie saw the shadow side of Catholicism, but seems to minimize the shadow side of Protestantism. It was the Augustinian tradition of obsession with sin and guilt and the corruption of the human will that led to Luther’s tormented ferocity; to Calvinism’s making predestination practically the whole of the Christian message; to the burning of witches; and, after all, Barth’s theology was itself called “neo-orthodox.” Hardly a line of vision. If you wanted to be unfair in the other direction, you could counterpoise all this against enlightened Catholics like Erasmus and Nicholas Cusanus and Rabelais. Norrie knows all this–in fact, he says some of it in Fearful Symmetry. But when he gets emotional he tends to think only of the bad side of Catholicism and the good side of Protestantism.

Continue reading →