httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DL5tjGK-x-g

Glenn Beck exhibits his brute talent for race-baiting and incitement to violence

Frye in Words with Power:

When the rhetorical occasion narrows down from the historical to the immediate, as at rallies and pep talks, we begin to see features in rhetoric that account for the suspicion, even contempt, with which it was regarded so often by Plato and Aristotle. Let us take a rhetorical situation at its worst. In intensive rhetoric with a short-term aim, there is a deliberate attempt to put the watchdog of consciousness to sleep, and the steady battering of consciousness become hypnotic, as the metaphor of “swaying” an audience suggests. A repetition of cliche phrases is designed to bring about a form of dissociation. The dead end of all this is the semi-autonomous monster called the mob, of which the speaker is now the shrieking head. For a mob the kind of independent judgment appealed to by dialectic is an act of open defiance, and is normally treated as such.

We spoke of the endlessness of argument in the conceptual area, but rhetoric has an ad hominem or personal weapon available to stop argument. One may be told, “You just say that because you’re an atheist, a Communist, a Jew, a Christian, or because you had a castrating mother,” etc., etc. Such verbal weapons are illegitimate in the conceptual mode, where an impersonal basis is assumed. But they play an important role in ideology–not always a sinister or violent role, as one may also be led to examine one’s position to see what limitations are built into it. (CW 26, 32-3)

That last point is subtle and reassuring. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with ad hominem arguments in the right context — we may indeed be called upon to rethink our stand on issues in light of personal biases. Satire, of course, completely depends upon the ad hominem affront, and it is perhaps the most direct assault on the inadequacies of ideology that literature affords.

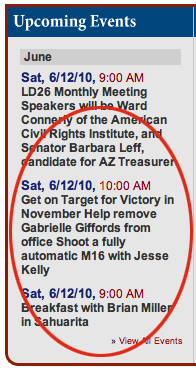

And that’s the difference I see between left and right in the most readily available public discourse. The left tweaks the nose of the right with fact-based mockery, and the right responds with death threats and talk of “second amendment remedies,” which predictably leads to violence. The left has Jon Stewart whose satire is usually most devastating when running a piece of footage that provides a missing piece of crucial information; the right has Glenn Beck whose involuted paranoid fantasies seem only intended to leave his audience unmoored and waiting for him to tell them who to hate next. While it’s true that you don’t want to mess with Matt Taibbi, he’ll never threaten you with violence or unleash a horde of angry minions upon you. But if you cross Sarah Palin, she’s capable of putting a target on you while barking “RELOAD” to an already irrational mob. One is acceptable and enriching civilized behavior, the other is psychopathy.