httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mc9eHI3ieQk

The Young Socialists of Catalonia in Spain have produced this video to encourage people to vote in upcoming regional elections. It’s caused a bit of a stir, but most people (politicians excluded) don’t seem to have much trouble with it.

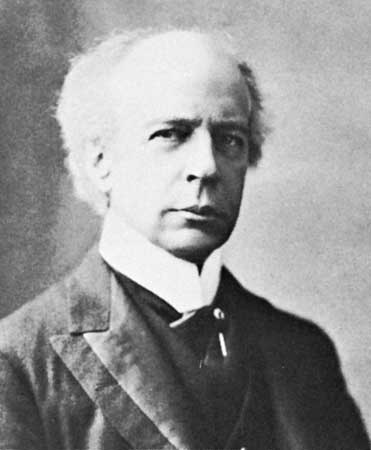

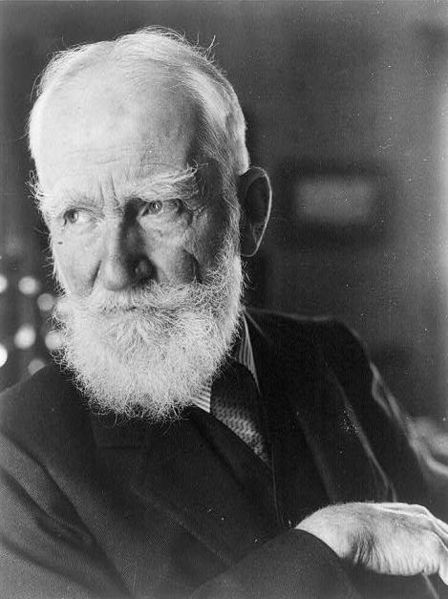

According to Frye, sex is of course a primary concern, and the right to vote is the peak experience of citizenship, so it seems natural enough that they come together at some point. Maybe this is it. Frye in conversation with David Cayley:

Then you get the other account [of creation] in chapter 2 [of Genesis], which begins with a garden and deals with animals as domestic pets. The imagery is oasis imagery. It’s all gardens and rivers. And the emphasis is heavily on the distinctness of the human order. First you get Adam, then you get Eve as the climax of that account of creation. Obviously, that describes a state of being in which man and his environment are in complete harmony. Then comes the fall, which is first of all self-consciousness about sex, or what D.H. Lawrence calls “sex in the head.” That really pollutes the whole conception of sexuality and thereby pollutes in the same way the relation of the human mind to its environment. (CW 24, 1023)

Not to be a total jag about this, but there is something deeply satisfying about seeing a woman depicted as having an orgasm while voting: it eagerly embraces both liberated female sexuality and gender equality. As Frye notes, if, according to Judeo-Christian myth, humanity fell by way of a woman, then it will rise again as one. Why shouldn’t something like this be winkingly suggestive of that? Traditionally, nothing about sex is more threatening than female sexuality, which has always been about sexual shame generally and female subordination specifically. This sort of thing fully exposes the fact that some people (including young socialists) are well past that. Woman is after all, Frye suggests, the climax of creation.