httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6PAABJ0hH84

Rossetti’s “When I am Dead, My Dearest”

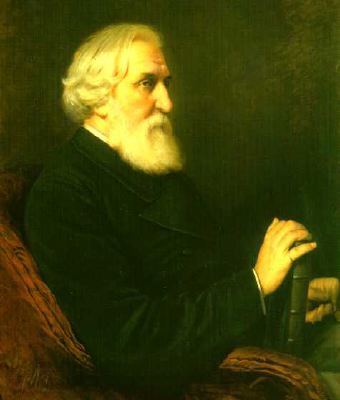

Today is Christina Rossetti‘s birthday (1830-1894).

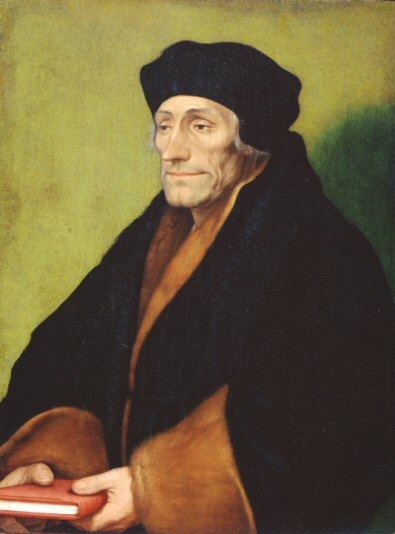

Frye in “The Bride from the Strange Land,” his essay about the Book of Ruth:

In English literature the best known allusion to Ruth is Keats’s Ode to a Nightingale, where the poet says that the nightingale’s song may have pierced “Through the heart of Ruth, when, sick for home, / She stood in tears among the alien corn” [stanza 7]. It is a beautiful but curious reference: as we say, Keats certainly knew the Book of Ruth, but there no hint in it that Ruth was ever homesick for Moab or that she regarded the corn fields around her as in any sense alien: after all, her late father-in-law still owned some of them. The tendency to sentimentalize the story recurs in a sonnet by Christina Rossetti, called Autumn Violets, which has as its last line “a grateful Ruth tho’ gleaning scanty corn.” This is not, it is true, a direct reference to the Biblical book, but we may note that actually, thanks to Boaz’ patronage, Ruth did fairly well out of her gleaning. I make these somewhat pedantic comments because I suspect that one reason for the comparative neglect of the Book of Ruth by later writers is the irrepressible cheerfulness of the story, which is all about completely normal people fully understanding one another, and leaves the literary imagination with very little to do. That said, we could justify the Keats allusion by observing that Ruth does not give the impression of being merely a mindless puppet of Providence, and may well have had darker and deeper feelings than the narrative presents. (CW 4, 112-13)