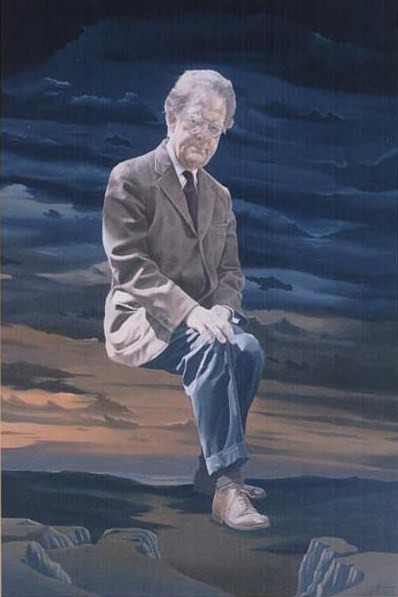

This is Jean O’Grady’s first post — and the first paper to be added to our new Frye Festival Archive in the Frye Journal. Jean is the associate editor of the Collected Works of Northrop Frye, published by University of Toronto Press. She gave this paper at the Frye Festival in Moncton in 2007. An expanded version of it appears in Northrop Frye: New Directions From Old, published by University of Ottawa Press.

Sir Edward Elgar, composer of sublime symphonies, concertos, and choral works, found it infuriating to be almost universally identified as the author of the Pomp and Circumstance marches. I suspect that Frye found it similarly irksome, after the publication of his Anatomy of Criticism in 1957, to be known, not for having mightily mapped the literary universe, but as the critic who said that critics shouldn’t make value judgments. Of course he had made it clear that he was talking about the academic critic, the theorist of literature, and not the reviewer in the local newspaper, but still his assertion had been found highly controversial. The polemical introduction to the Anatomy had actually made two points which kept coming back to haunt Frye: first, that criticism was, or should be, a science; and second, that the critic’s function was not to say whether a work of literature was good or bad, successful or unsuccessful, but to tell us what sort of work it was. The two points are in fact related, since Frye was trying to move away from the stereotype of the critic as a gifted amateur of exquisite discrimination who journeyed among the masterpieces, poking disdainfully at the second-rate with his gold cane. Instead, he proposed a survey of all the literature that has been written, highbrow or popular, in fashion or out of fashion, in order to map out its genres, types, and archetypes: this was a structure of knowledge that, just like the sciences and social sciences, could be taught and that each scholar could help to build up. As Frye said in The Well-Tempered Critic, “Without the possibility of criticism as a structure of knowledge, culture . . . would be forever condemned to a morbid antagonism between the supercilious refined and the resentful unrefined” (136).

I first read the Anatomy as a student, in 1962, and I can hardly tell you how exciting and liberating this notion was, along of course with the Anatomy‘s actual demonstration of archetypal patterns, of plot shapes that repeated themselves from Spenser to Harlequin romances, and of the unsuspected interrelations among works. Literature was so much richer and more fascinating when one could start to make connections rather than worrying about one’s possibly bad taste! The book opened up wide vistas of intellectual adventure in my chosen field, and made me feel like a participant in and contributor to a glorious endeavour.

The inclusiveness of the Anatomy, its openness to works of popular literature or of dubious morality, should surely endear Frye to the various types of postmodernist, feminist, or postcolonial critics, who complain that the dominant group or class has defined a “canon” that unfairly excludes some works or makes them marginal. Frye was precisely against singling out what he called a “selected tradition” of great works, which would inevitably turn out to have been written by dead white males. No narrow moral criteria apply in the Anatomy, which contends that “morally the lion lies down with the lamb. Bunyan and Rochester, Sade and Jane Austen, . . . all are equally elements of a liberal education” (14). As Frye told Imre Salusinsky in an interview, “The real, genuine advance in criticism came when every work of literature, regardless of its merit, was seen to be a document of potential interest, or value, or insight into the culture of the age”.

Value, as Frye expressed it in this early stage, resides in literature as a whole. As we read, we absorb an imaginative pattern of apocalyptic or demonic imagery and of narratives that fall into the four basic types of comedy, tragedy, romance, or irony; each individual poem or work helps to fill in or reinforce the overall pattern. As Frye put it in The Educated Imagination, “Whatever value there is in studying literature, cultural or practical, comes from the total body of our reading, the castle of words we’ve built, and keep adding new wings to all the time” (39). This total pattern, “the range of articulate human imagination as it extends from the height of imaginative heaven to the depth of imaginative hell” (EI, 44), is what Frye calls “the revelation of man to man”. Such a verbal universe, built up equally by Biblical epics and the most run-of-the-mill adventure stories, provides a model or goal for humankind’s work, thus giving literature a vital role in the building up of civilization.

Continue reading →