B.W. Powe will be speaking at York University on October 21, 5-7 pm: “Apocalypse and Alchemy: Marshall McLuhan and Northrop Frye”

Category Archives: Frye and Contemporary Scholarship

Frye Alert: Who is Professor Mondo?!

The little we know is intriguing. He is, in his own words, a “dad, husband, mostly free individual, medievalist, writer, and drummer.” He very reassuringly quotes Chaucer: “Gladly wolde he lerne and gladly teche.” Even more reassuringly, he’s a fan of Frye. His blog’s banner rather enigmatically features this quote from the superior 80’s teen comedy Better off Dead: “Once a champion, now a study of moppishness.” Like the movie’s protagonist, played by John Cusack, the professor may be a quasi-tragic figure, who by necessity moves furtively and unappreciated through the hushed halls of academe. Most of this, of course, is irresponsible speculation.

You can find the good professor here. His lead post today is “How Twigs Get Bent: Northrop Frye,” which talks about his growing interest in Frye both as a medievalist and as a fan of detective fiction. He also mentions discovering our website. I’ve bookmarked him and intend to read him daily. I hope you’ll do the same.

Centre for Comparative Literature Update

Events seem to be moving quickly at this point, and we’ll keep you apprised as best we can. Here, therefore, are the posts that have gone up so far on this issue:

Jonathan Allen discusses the proposal when it first became public two weeks ago here.

Globe & Mail story here.

Bob Denham’s letter to U of T President Naylor here.

Jonathan Allen describes the unique work the Centre does and provides futher links in support of it here.

Natalie Pendergast discusses the closure of the centre in the context of Canada’s wider “cultural famine” here.

Alvin Lee’s letter to the editor of the Globe & Mail here.

Michael Dolzani’s letter to President Naylor here.

Centre for Comparative Literature: Letter to President Naylor

Here is my letter to University of Toronto president Naylor regarding the Centre for Comparative Literature

Dear President Naylor,

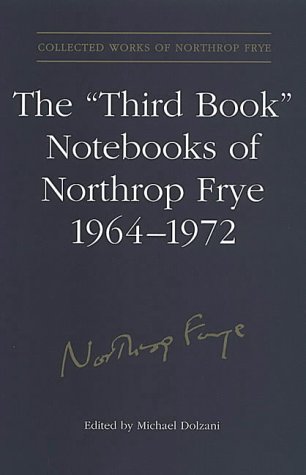

I write this on the 98th birthday of Canada’s most famous literary scholar, Northrop Frye. It turns out, unfortunately, not to be a very happy birthday. I have just learned, with considerable shock, of the plan to abolish the Centre for Comparative Literature, founded by Frye back in 1969. I am writing, as an alumnus of the University of Toronto, as Frye’s former research assistant, and as one of the editors of the Collected Works of Northrop Frye project published by the University of Toronto Press, to ask the University to reconsider its decision.

I will always be grateful to the University for taking a chance in 1978 and admitting a student from an unknown small college in Ohio. Although my experience in English was completely positive, I was sometimes told by other graduate students that Comparative Literature was where the really exciting stuff was going on. From everything that I have read, that Centre is as vigorous and important now as it was then, yet that has not been a factor in the decision. Yes, it is good that people are not going to lose their jobs, but there will be another kind of loss, for the kind of scholarship enabled by Comparative Literature will become impossible.

To non-academics, “comparative literature” may seem just one more arcane, narrow specialization. If people do not even know what comparative literature is, it is understandable if they are not motivated to fund it. Comp Lit is a centrifugal approach to literary studies that reverses the centripetal approach of a traditional English department. What I mean is that, if you have a degree in English, your program restricts you to the literature of one language, and usually one country and historical period. When you go on the job market, you peddle yourself as, say, “eighteenth-century British.” The centripetal approach originated in the nineteenth century and remains valid; my own degree is in English. However, it is next to impossible within such a framework to study English centrifugally, in terms of its connections with other languages, literatures, and cultures. Yet those connections are crucial on three levels, linguistic, literary, and social. As Frye pointed out in an address to the Canadian Comparative Literature Association in 1974, “In English literature, the major influences have been Latin, French, and Italian: the influence of Old English on later developments has been minimal, as has that of medieval English apart from Chaucer. The most familiar schemata of English poetry, rhyme and meter, were taken over from French. And underlying a great deal of its fiction is a solid basis of popular literature, in folktale and ballad, which has travelled around the world without regard to linguistic barriers.” To this we may add that when literary theory came of age in the second half of the twentieth century, there was great difficulty accommodating it in traditional English departments, because theory by definition asks general rather than specialized questions. Frye’s own wide-ranging work was an influential example here. In a world that is becoming more and more interconnected, and more and more obsessed by its own interconnectedness, it seems incomprehensible that the University would seek to abolish a discipline that studies exactly those connections.

I know that there are financial considerations involved. Fifty-five million dollars is from one point of view a lot of money. From another point of view, it is the bonuses of perhaps six CEOs. The question is what our values are. The University’s financial crisis has been largely created from outside itself. We owe the global financial meltdown to people who did not study the humanities, and who consequently made foolish and destructive decisions out of blindness. No, the study of literature does not necessarily lead to wisdom and sensitivity—but it is one of the few things that can enlarge our being if we are open to it. That was Frye’s faith. I truly hope the University may reverse its decision and find other ways to close the budget gap.

Respectfully,

Michael Dolzani

Professor of English

Chair, English Department, Baldwin-Wallace College, Berea, Ohio

Alvin Lee: Letter to the Globe & Mail

Here is my letter to the editor yesterday regarding the Centre for Comparative Literature

Dear Editor,

I have not seen the Gertler report with its recommendation to close the Centre for Comparative Literature at the U of T and to fold it (what would be left of it) into a School that would also include the five departments of Italian, German, East Asian Studies, Slavic languages and Spanish and Portuguese. As a university scholar/teacher and a university administrator, I saw firsthand what precedes and follows such decisions.

Because each individual language and literature department is a linguistic minority in an English-language university, its very existence depends on unusual professional commitment and hard work. It also depends on its ability to convince budget officers that when you fold the cultural milieu of a language and literature department into a broader English-speaking mix, you destroy the identity of the original, and much of its reason for being. The professors no longer use the identifying language in most of their daily work, the staff have to function mainly in English, and the language context in which students are meant to become proficient ceases to exist.

The paramount strength of the graduate programs in the Centre for Comparative Literature has been its ability to attract, for work at an advanced level, able students from around the world who have had deep exposure while undergraduates to more than one language and literature in at least two of the kind of department that would disappear into the proposed new School. There is a close symbiotic relation between the U of T Centre and the separate language and literature departments at the U of T and the other universities from which the students come. As the Northrop Frye Professor of Literary Theory in the Centre in 1991-2, I saw this fact in every class discussion: the accuracy and incisiveness of what a young scholar says about a literary text is convincing only when the text is being read in its original language. It is an important part of Frye’s legacy that he knew this and that he championed the need for just the kind of intellectual and imaginative work that the U of T Centre has been doing for 41 years.

Sincerely

Alvin A. Lee

Professor of English Emeritus and President Emeritus, McMaster University

General Editor, The Collected Works of Northrop Frye, 30 vols (University of Toronto Press)

Natalie Pendergast: Canada’s Cultural Famine

Bryan Lee O’Malley‘s cover for Shojo Beat

Is it any coincidence that the terms “starving artist” and “poor student” have become stereotypes in this country? As one of the latter I can tell you that although these terms may stick around for a long time, what they refer to—their “signified”–certainly will not. No, I’m afraid that if one continues to get poorer and poorer, hungrier and hungrier, he/she will eventually waste away. If left to starve, if left homeless for long enough, the artist and the student will die.

Right now, this type of negligence is occurring at the University of Toronto. The Centre for Comparative Literature is in a battle for its life. By extension, this battle is only one example of the perpetual struggle for artists and humanities scholars who promote and study culture in Canada. We are in the midst of a bona fide arts and culture famine.

Margaret Atwood, in an article published in the Globe and Mail, on Wed., Sept. 24th, 2008 and updated on Tues. Mar. 31, 2009, wrote the following:

[Prime Minister Stephen Harper] told us that some group called “ordinary people” didn’t care about something called “the arts.” His idea of “the arts” is a bunch of rich people gathering at galas whining about their grants. Well, I can count the number of moderately rich writers who live in Canada on the fingers of one hand: I’m one of them, and I’m no Warren Buffett. I don’t whine about my grants because I don’t get any grants. I whine about other grants – grants for young people, that may help them to turn into me, and thus pay to the federal and provincial governments the kinds of taxes I pay, and cover off the salaries of such as Mr. Harper. In fact, less than 10 per cent of writers actually make a living by their writing, however modest that living may be. They have other jobs. But people write, and want to write, and pack into creative writing classes, because they love this activity – not because they think they’ll be millionaires.” She prefaced these concerns by citing that the Conference Board estimates Canada’s cultural sector to have generated $46 billion, or 3.8 % of Canada’s GDP in 2007. She threw in another quote from the Canada Council that the sector consists of 600,000 jobs, which is the same as agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining oil and gas and utilities combined.

Her frustration is directed toward the lack of funding given to Canadian artists, but there is another—perhaps more painful—reality that lends to the anxious tone of her words: the lack of support and appreciation from Stephen Harper. It seems that “ordinary people” have trouble seeing the value in arts and culture, and this simple point is at the very core of the current Canadian divide between humanities scholars, writers, researchers, teachers, students, enthusiasts, and others. What will it take to prove that arts and culture are important?

In light of the recent World Cup Football Championship, I find myself wondering why it is that sports like soccer and hockey seem to have such a huge cultural following. When Canada won the Winter Olympics hockey final, I knew everything about that game,even though I am not a hockey fan. I could not avoid it—it filled up every space of my life: the people in the streets prevented me from going home, every channel on TV was broadcasting highlights, the neighbours’ celebratory cheers were ringing in my ears. The difference is that, when it comes to hockey, we Canadians feel a personal attachment. We “own” it.

By contrast, the arts are less a part of our culture as Canadians, and more a cultish obscurity. When, for example, I discovered that the Scott Pilgrim manga artist, Torontonian Bryan Lee O’Malley was coming to The Beguiling comic book store this summer, I nearly screamed with excitement. And what is more astounding, the famous artist/author, whose manga series is now being adapted into a major motion picture starring Canadian Michael Cera, is charging nothing for his book release party that includes a concert with four bands. In Toronto, I am sure that most people could not recognize the name Bryan Lee O’Malley despite his fame in the comic reading (under)-world and even in the entire high school and university student world!

The Incomparable Centre for Comparative Literature

Today is Frye’s birthday, and it has been just about two weeks since we heard the news that the Dean of Arts and Sciences, Meric Gertler, and the Strategic Planning Committee had recommended the closure of the Centre for Comparative Literature which Frye founded 40 years ago. The news was a complete shock. The director of the Centre, Neil ten Kortenaar, in his letter to the dean begins with this very admission:

My initial shock at the news of the proposed disestablishment of the Centre for Comparative Literature has become absolute dismay as the meaning of this proposal has become clear to me. The news comes at a time when Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto was being thoroughly reinvigorated and we were looking forward with excitement to our future.

I can only agree with these sentiments. I was initially shocked by the recommendation and then slowly but surely began to realise the ramifications of such a decision. Ten Kortenaar cites a number of these in his letter.

But, on a much more personal level, the type of research that I do simply cannot be done elsewhere. I chose to attend the University of Toronto, and more precisely the Centre for Comparative Literature, because of its connections to Northrop Frye. When I arrived at the University, I told the faculty of the Centre that my project would focus on Frye’s influence, especially with respect to Harold Bloom. Indeed, in October, I submitted to the Centre a SSHRC proposal called, “Anxieties of Criticism, Anatomies of Influence: A Study of Northrop Frye and Harold Bloom.” In April, I found out that I had been awarded a SSHRC. Since then I have written an article with a very similar title that recently appeared in the Canadian Review for Comparative Literature. It may appear that I could have completed this research anywhere. But that is not the case, I very much needed the University of Toronto and the Centre for Comparative Literature because it provided the archives and the intellectual guidance of people like Linda Hutcheon, J. Edward Chamberlin, and Eva Kushner.

My current research continues with ideas stemming from Northrop Frye’s theories of literature, particularly romance. My dissertation considers literatures written in English, Spanish, French, and Portuguese. This dissertation simply could not happen elsewhere. The study follows Frye’s dictum that “popular literature […] is neither better nor worse than elite literature, nor is it really a different kind of literature” (CW XVIII:23); and thus, my study includes everything from George Eliot and Marcel Proust to Twilight and Harlequin romances. Only the Centre for Comparative Literature could provide a home for such research and only the Centre would encourage such research. The Centre has afforded me many opportunities to explore romance and present these ideas at international conferences. In April, I was at the American Comparative Literature Association’s meeting in New Orleans and NeMLA meeting in Montreal; in May at Congress in Montreal where I presented at the Canadian Comparative Literature Association’s meeting as well as the Canadian Association of Hispanists, in August I will be at the International Association for the Study of Popular Romance’s conference, and in September at a conference on monsters at Oxford.

I look around now at the Centre for Comparative Literature and realise that this Centre is, even in its darkest hours, a powerhouse for intellectual inquiry. Today, the Centre found itself on the front page of the Globe and Mail receiving national exposure. I think I can say that for many of my colleagues this was a huge – and much needed – surprise.

I urge readers of this blog to consider the future of Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto. We have a series of ways you can follow our story and I provide to you a series of links:

www.savecomplit.ca — Main Resource and Information Page; if you send letters to the Dean, Provost, and President, we will happily publish them here. All media stories will be included on this webpage.

www.PetitionOnline.com/complit/petition.html — Petition to Save Comparative Literature at the University of Toronto. Major figures in Comparative Literature have already signed (as have many Frye Scholars): Ian Balfour, Svetlana Boym, Rey Chow, Jonathan Culler, Jonathan Hart, Nicholas Halmi, Linda Hutcheon, Andreas Huyssen, Ania Loomba, Franco Moretti, Tilottama Rajan, Germaine Warkentin.

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Save-Comp-Lit-at-U-of-T/128346170533811 — A Facebook page with information as it becomes available.

http://twitter.com/SaveComplit — Our Twitter account which will post links to news stories.

And, of course, we will continue to update the Frye community here at The Educated Imagination.

Centre for Comparative Literature: Letter to the President

Below is a letter I sent yesterday to University of Toronto President Naylor, with copies to both Dean Gertler and the provost, regarding the proposed closing of the Centre for Comparative Literature.

Dear President Naylor,

The discussion about the fate of comparative literature at the U of T might gain some measure of clarity from what Northrop Frye always emphasized, that cultural movements flourish when they are decentralized, unlike political and economic movements, which tend to centralize. When the study of culture is centralized, such as will occur if comparative literature is amalgamated into a unite‑and‑conquer proposal that brings the study of all languages and literatures together under one administrative umbrella, uniformity replaces unity and bondage supplants freedom. While the centralizing tendency may work in such social sciences as, say, Geography & Planning, it never works in the humanities. The centralizing movement erases identity. Dean Gertler has written about how the centralizing movement we call globalization should not trump the decentralized nation‑state, which remains a key space for organized labor (“Labour in ‘Lean’ Times: Geography, Scale, and National Trajectories of Workplace Change”). While the parallels between internationalism and an amorphous department of languages and literature, on the one hand, and local autonomy and a separate identity of comparative literature, on the other, are not exact, to pay tribute to the former in what Gertler calls “lean” economic times is surely short‑sighted.

As Frye has written, “to distinguish what is creative in a minority from what attempts to dominate, we have to distinguish between cultural issues, which are inherently decentralizing ones, and political and economic issues, which tend to centralization and hierarchy” (“National Consciousness and Canadian Culture”).

This past year I was an external reviewer for a dissertation by a Ph.D. student in Comparative Literature at the U of T. It was an exceptional piece of work, combining a number of disciplines––language, game theory, mathematics, critical theory, music, painting––into a genuine contribution to humanistic learning. It will be a depressing state of affairs if such extraordinary and mature scholarship is no longer permitted to flourish at the U of T. Everyone in the field, even those of us at a distance, knows what a distinguished program Comparative Literature at the U of T is. To consign to the dustbin an exemplary program founded by Canada’s greatest man of letters would be a travesty of the highest order, and it would cause those of us who see the U of T as a flagship university in both Canada and the rest of the world to lose faith.

Yours truly,

Robert Denham

John P. Fishwick Professor of English, Emeritus, Roanoke College

Frye in Our Colleges and Universities Today (2010)

The critical canon, like the literary one, naturally changes over time. The anthology of criticism I used as a student in the 1960s––The Great Critics, ed. Smith and Parks (3rd ed., 1951)––included a number of critics very seldom read nowadays (e.g., Henry Timrod). The first edition of this anthology (1932) included Marco Girolamo Vida; the second edition (1939), Antonia Sebastian Minturno. The fact that critics come and go is a commonplace observation. Henry Hazlitt’s The Anatomy of Criticism, widely read in the 1930s, has more or less disappeared. Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism has had a much better fate, but the question is frequently raised about Frye’s status today. Has he, like Henry Timrod, disappeared into the dustbin of history? “Who now reads Frye?” asks Terry Eagleton, rhetorically.

In an entry in this blog some time back (26 September 2009) Jonathan Allan reported on the contempt for Frye he heard at a Canadian Studies Conference. Allan, however, goes on to surmise that “Frye, in most instances, is now covered in survey courses of literary theory.” I suspect this is the case, though descriptions of such courses are often so brief and lacking in specificity that without a syllabus at hand it is impossible to know what’s on the reading list. Still, there are indications that Frye is still being read. His Fearful Symmetry was among the most frequently borrowed books from the English Faculty Library at Oxford during the Trinity Term 2009 and the Hilary Term 2010, and if we survey what is available on the web, we discover that Frye has not at all disappeared from college and university course descriptions and syllabi. The list that follows records the results of such a survey. My guess is that it represents only a fraction of those courses in which Frye is required or recommended reading or is otherwise the focus of an entire course or of a course unit. (I quit searching after I had recorded 400 entries.) There are doubtless a number of course in twentieth‑century literary criticism, Shakespeare, Blake, Canadian literature, and other subjects where Frye is read, but, again, this information is not always available in the catalogue course descriptions that are available on the web.

The list represents courses offered during the past ten or so years. (A few entries are for high school courses and M.A. exam reading lists). In most instances the entries provide the course title, name of the instructor, the year offered, and a brief account of the “Frye content.” The list is extraordinarily fluid: instructors come and go, courses and added and dropped, catalogue listing changes from one year to the next, and web sites go dead, and URLs are broken. Still, the list reminds us of the widespread attention Frye continued to receive during the past decade, and so it serves as an answer, at least in part, to Eagleton’s rhetorical question, “Who now reads Frye?”

Bloggers are invited to send me additions to the list (denham@roanoke.edu).

“A New Handbook of Literary Terms”

From the preface to A New Handbook of Literary Terms by David Mikics (Yale University Press, 2007)

An ideal bibliography should include older, respected works that continue to shape our sense of what criticism can to. Auerbach’s Mimesis, first published in Switzerland in 1946, is still the indispensable book on realism. Mimesis is referred to repeatedly here, as is Northrop Frye’s definitive Anatomy of Criticism (1957), the best treatment of genre. Frye, like Auerbach, opened up a whole new world for criticism with his book, which continues to be central to literary study fifty years after it was written. A student who wants a sure grounding in literary history, and at the same time an exhilarating experience of criticism at the height of his powers, would do well to read Mimesis and Anatomy of Criticism—along with other synoptic and original works like James Nohrnberg’s The Analogy of the Faerie Queene, Harold Bloom’s The Visionary Company, Ian Watt’s The Rise of the Novel, Geoffrey Hartman’s Beyond Formalism, Martin Price’s To the Palace of Wisdom, Martha Nussbaum’s The Fragility of Goodness, Hugh Kenner’s The Pound Era, Irving Howe’s Politics and the Novel, Ronald Paulson’s Satire and the Novel, Frank Kermode’s Romantic Image, and William Empson’s Some Versions of the Pastoral. Curtius’ European Literature the Latin Middle Ages remains the essential guide to the topoi that engage medieval and Renaissance literature. These fourteen books, some of them published as long ago as the 1930s (Empson), provide the background and assumptions for much later work. Some more recent volumes, like Margaret Doody’s The True Story of the Novel, share the ambitions and innovative character of those I have just listed. The Handbook takes care not to slight younger critics—there are quite a few references from the new, twenty-first century—but I have emphasized those books that have already stood the test of time.