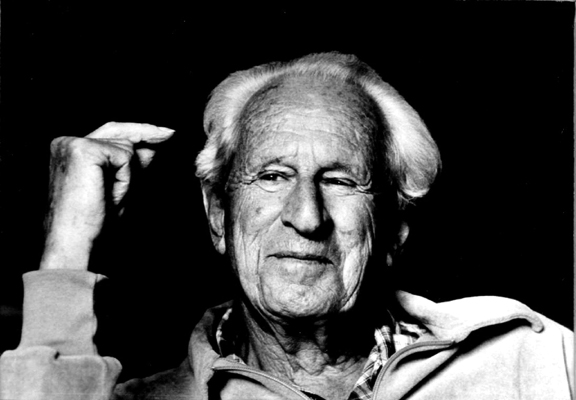

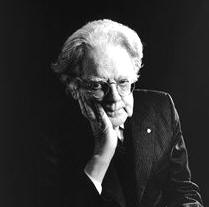

This is a meditation and mini‑sourcebook, triggered by Michael Dolzani’s uncommonly perceptive post (not uncommon, of course for Michael, my editorial sidekick, who, as I’ve said several times in print, is a reader of Frye without equal). Here’s hoping that he’ll continue to share with us what’s on his mind.

I

Angels for Frye belonged to a complex of entities he called the world of “fairies and elementals.” In his notebooks he keeps promising himself to write an article of “fairies and elementals” (On the topic, see Late Notebooks [CW 5], 189–90, 195, and Notebooks and Lectures on the Bible [CW 13], 54; Notebooks on Romance [CW 15] 143, 144; Notebooks for “Anatomy of Criticism” [CW 23], Notebook 25, par. 7 [unpublished but posted in the Library as sect. 7 of “Unpublished Notes”]). He never got around to writing the article, but there are hints here and there about what the article would contain. At one point in his Great Code notebooks Frye appears to conceive of three strands in the “elemental” esoteric traditions:

1. The fairy world itself

2. The bardo world

3. The “total magnet or anima mundi which accounts for mesmerism, telepathy, clairvoyance, second sight & magical healing cures” (Notebooks and Lectures on the Bible, 54). Frye sometimes calls this third strand the soul-world or Akasa (Sanskrit for “space” or “ether”), a term that he adapted from Madame Blavatsky. Angels belong to what he refers to as “non-human forms of more or less conscious existence” (ibid.) In Anatomy of Criticism, these “forms” belong to the existential projection of romance (64), meaning that the writers of romance accept the world of fantasy as “true” and so populated their stories with angels, fairies, ghosts, demons, and the like. Angels, of course, occupy their place in Frye’s accounts of the ladder of being on the rung between the human and the divine. They belong as well, in Blake’s four‑storied cosmos, to Beulah, and they are a part of what Frye called in his first essay on Yeats “the hyperphysical world” (Fables of Identity, 227). Twenty years later he describes this world as

the world of unseen beings, angels, spirits, devils, demons, djinns, daemons, ghosts, elemental spirits, etc. It’s the world of the “inspiration” of poet or prophet, of premonitions of death, telepathy, extra-sensory perception, miracle, telekinesis, & of a good deal of “luck.” In the Bible it’s connected with Lilith & other demons of the desert, with the casting out of devils in the gospels, with visions of angels, with thaumaturgic feats like those of Elijah & Elisha, & so on. Fundamentally, it’s the world of buzzing though not booming confusion that the transistor radio is a symbol of. (Notebooks and Lectures on the Bible, 90)

II

I wonder if in Frye’s anguished katabatic experience of Helen’s death in Cairns we might not have a conjunction of the oracle and wit insight that was the essence of his Seattle epiphany. This occured to me by looking again at the ultimate and penultimate remarks of Helen before she died––after which Jane Widdicombe becomes a guardian angel.

The oracle: “Besides, when Jane told her she was in hospital and had to get better before she could go home, she said ‘I can take that from you.’ When I tried to say the same thing, she said ‘Don’t be so portentous.’ It was the last thing she said to me, and it sounds like an oracle. Meanwhile there is Jane, a daughter sent by God instead of nature. Guardian angels take unexpected but familiar forms, as in Homer” (Late Notebooks, CW 5, 137–8).

The wit: “She died at 3.10 p.m. on August 4 (the medical attendants said 3.30, but I happen to know when she actually left me). She was a gentle and very pure spirit, however amused or embarrassed she might be to hear herself so described. The day before her death the intravenous machine ran out of fluid and started ticking: Helen opened an eye and said “Is that your pet cricket?” I am grateful that in practically the last thing I heard her say there was still a flash of the Helen I had known and loved for over fifty years” (“Memoir,” Northrop Frye’s Fiction and Miscellaneous Writings, CW, 42).

Michael Dolzani shows how Frye, in all those passages about Helen in Notebook 44, moves from a negative to a positive faith, having been transported from the abyss where he has confronted her death to some form of apocalyptic revelation, where Helen has now become for him a Beatrice or Laura. He needs no longer now accuse himself of having murdered her by taking her to Australia.

Continue reading →