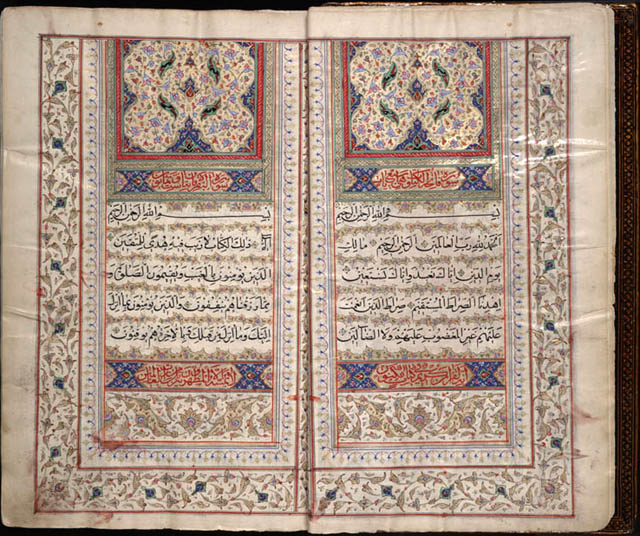

[Wesley Memorial United Church, Moncton, NB]

In his book Northrop Frye: Religious Visionary and Architect of the Spiritual World, Bob Denham lists the half-dozen spiritual illuminations that Frye experienced during his lifetime, and quotes Frye from the late notebooks: “I have spent the greater part of seventy-eight years in writing out the implications of insights that occupied at most only a few seconds of all that time.”

“Moments of intensity,” Frye called them. Epiphanies. Insights. Illuminations. Intuitions. The first occurred in Moncton, one day when he was walking from his home on Pine Street to Aberdeen High School, a distance of about 10 blocks. In an interview with Robert Sandler (recorded Sept. 20, 1979, and quoted in John Ayre’s biography), Frye

remembered walking along St. George St. to high school and just suddenly that whole shitty and smelly garment (of fundamentalist teaching I had all my life) just dropped off into the sewers and stayed there. It was like the Bunyan feeling, about the burden of sin falling off his back only with me it was a burden of anxiety. Anything might have touched it off, but I don’t know what specifically did, or if anything did. I just remember that suddenly that that was no longer a part of me and would never be again.

In April, 2011, when Michael Happy was in Moncton to give a talk at the Frye Festival, he and I spent an afternoon exploring the various Frye sites that mark the city, sites that go back to his time here in the 1920s and new sites created by the festival in the last 13 years. From his house at 24 Pine Street and the Wesley Memorial Church on Cameron we drove and walked along St. George Street, trying to imagine where it was exactly that the albatross was lifted. A likely spot seemed to be at the corner of St. George and Lutz, where the Roman Catholic Cathedral towers above all else and is suitably massive, dark, and forbidding. (Though I know from experience it houses one of the great organs in Canada, and is central to Acadian culture and history.) We snapped pictures of the near-by gutter, thinking we’d surely found the spot. Unfortunately, it turns out that the Cathedral, a fact I should have known, was only built in 1939. So we still do not know where it happened. The important thing, for Frye and for us, is that it did happen.

Yet looking back on the Moncton illumination, Frye realized, as he said to David Cayley in December, 1989 (having said something similar in the Sandler interview):

I wasn’t really brought up with that garment on me at all. Mother told me a lot of nonsense because her father had told it to her, and she thought it must be true and that it was her duty to pass it on. But something else came through, and you know how quick children are at picking up the overtones in what’s said to them rather than what is actually said. I realize that Mother didn’t really believe any of this stuff herself… She thought she did believe it. She thought she ought to believe it. But I can see now that as a child I picked up the tone of common sense behind it. Mother had a lot of common sense in spite of all that stuff.

It’s easy to hear in these words a great affection for his mother, who is the one after all who got him going at the age of 3 or so, with reading and music and much else. It’s one of the reasons no doubt, this affection, that brought him to Moncton in Nov., 1990, two months before his death, to lecture at l’université de Moncton, give a talk at Moncton High School, and in general receive a hero’s welcome. This may have been his only visit to Moncton since the 1940s, when his mother died. One of his primary wishes was to visit her gravesite in Elmwood Cemetery. Continue reading