On Remembrance Day, remembering how Frye viewed war and peace and poetry, how he says in what is probably my favourite book of his, Words with Power, that working in words and other media, may be our only way to salvation on earth, that is, the only way to show instead of argue with the warmongers among the ideologues and/or the “psychotic apes”.

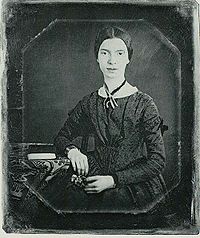

On In Flanders Fields:

It is perhaps not an accident that the best known of all Canadian poems, “In Flanders’ Fields,” should express, in a tight, compressed, grim little rondeau, the same spirit of an inexorable ferocity which even death cannot relax, like the Old Norse warrior whose head continues to gnash and bite the dust long after it had been severed from his body.

The Bush Garden: 150

On Ideologues:

I keep having a vision of a guide or preacher or some professional haranguer standing in front of a war cemetery in Flanders with a million crosses behind him and explaining how human aggressiveness has such essential survival value.

Late Notebooks 1982-1990: 678

On Human and Divine Commands:

In the Decalogue God says, “Thou shalt not kill,” or, in Hebrew, “Kill not.” Period, as we say now: there is nothing about judicial execution, war, or self-defence. True, these are taken care of elsewhere in the Mosaic code, because the commandment is addressed to human beings, that is, to psychotic apes who want to kill so much that they could not even understand an unconditional prohibition against killing, much less obey it.

The Great Code: 232

Cayley: Does the word also become a command?

Frye: It often takes the form of a command, yes. I think that the word of command in ordinary society is the word of authority, which relates to that whole area of ideology and rhetoric. That kind of word of command has to be absolutely minimal. It can’t have any comment attached to it. Soldiers won’t hang themselves on barbed wire in response to a subordinate clause. If there’s any commentary necessary, it’s the sergeant’s major’s job to explain what it is, not the officer’s. Now that is a metaphor, it’s an analogy, of the kind of command that comes from the other side of the imagination, what has been called the kerygmatic, the proclamation from God. That is not so much a command as a statement of what your own potentiality is and of the direction in which you have to go to attain it. But it’s a command that leaves your will free, whether you follow it or not.

Northrop Frye in Conversation: 182

On Human Peace vs Mythological Peace

In between these visions of creation comes the Incarnation, which presents God and man as indissolubly locked together in a common enterprise. This is Christian, but the answering and supporting “Thou” of Buber, which grows out of the Jewish tradition, is not imaginatively very different. Faith, then, is not developed by clogging the air with questions of the “Does a God really exist?” type and answering them with equal nonsense, but in working, in words and other media, towards a peace that passes understanding, not by contradicting understanding, but by disclosing, behind the human peace that is merely a temporary cessation of a war, the proclaimed or mythological model of a peace infinite in both its source and its goal.

Words with Power: 124-125