The Frye Festival is a whirlwind of activity, as anyone who has been here can testify. What started out as a two-day festival is now a week-long, non-stop celebration of the written word. A lot of our effort goes into our School / Youth Program. About 10,000 young people, at all grade levels, get to hear and meet Frye Festival authors. For some of the authors this is old hat, while for others it’s a new and (usually) very rewarding experience. Young people are directly involved in the festival in several other ways, through essay writing contests, volunteering opportunities, and one evening at the festival devoted completely to young writers still in high school – an evening we call ‘Café Underground’. Sometimes our focus on Frye gets a little blurred in all this flurry of activity, but we always come back. (We plan, of course, to come back in a big way in 2012, Frye’s centenary.) Frye, we believe, would whole-heartedly approve of our emphasis on young people and education.

Every year, as I mentioned in a previous post, we schedule two major talks or lectures, the Antonine Maillet – Northrop Frye Lecture and the ‘Frye Symposium’ Lecture. We also schedule three roundtable discussions where festival authors bring fresh insight to ideas and topics that (more often than not) have a fairly direct connection to Frye. We’ve had some remarkable exchanges over the years. My hope is that as we dig deeper into our archives (audio and video recordings, old computer files, etc.) we’ll be able to post some of this material on the blog. I remember, for example, a wonderful prepared statement that Glen Gill read at a roundtable in 2005, on the subject “Myth and Identity: The Role of Myth in Forming a Sense of Identity.” Other panelists on that round table were Jean O’Grady, Yves Sioui-Durand, and Maurizio Gatti. In April, 2000, at our very first roundtable, we asked the panelists (including David Adams Richards, France Daigle, Louise Desjardins, and George Elliott Clarke) to discuss Frye’s statement that “the regional is the real source of the poet’s imagination.” In 2003, with John Ralston Saul as moderator, we explored the topic “Mythology and National Identity,” with authors Bernhard Schlink, Naim Kattan, France Daigle, André Roy, and Joyce Hackett. A crowd of about 200, with the Governor General in attendance, set the room abuzz. After 10 years it’s become clear that our roundtables, relaxed, informal, aimed at the “sophisticated amateurs” in the audience, have become one of the most anticipated features of the festival.

But we’re not always successful in posing the right question or getting the right slant on a particular theme. Sometimes we pose a question that scares the public away, as in 2008, with “The Eros of Reading: Why Some Students Fall in Love with Reading and Others Do Not.” The discussion, with panelists Peter Sanger, Glenna Sloan, Monique Leblanc, and Andy Wainwright, was brilliant, and especially important in the context of New Brunswick’s terrible literacy statistics, but we failed to bring out the audience that it deserved. Sometimes we have a good question and excellent panelists, but they bring such different perspectives that they end up talking past one another. We are working on three roundtables for this April (two months from now!), a little worried that we haven’t got them quite right. We have a title for one of the roundtables (“Stories, and How They Work”) that is broad and vague enough that it might work just fine or might have trouble finding its feet, depending on the moderator and panelists. But with Jean Fugère as moderator, and Linden MacIntyre, Annabel Lyon, and two equally outstanding francophones, we have high hopes. The same is true of our Friday noon roundtable, with Jean Fugère again as moderator. The topic is “Writing Lives and Afterlives” and the panellists will include Nino Ricci, Daniel Poliquin, and Noah Richler. The idea is to explore what happens when fiction writers write biography, bringing the narrative gift to a non-fiction genre. They may end up exploring something very different, of course, much to our surprise and (if we’re lucky) delight.

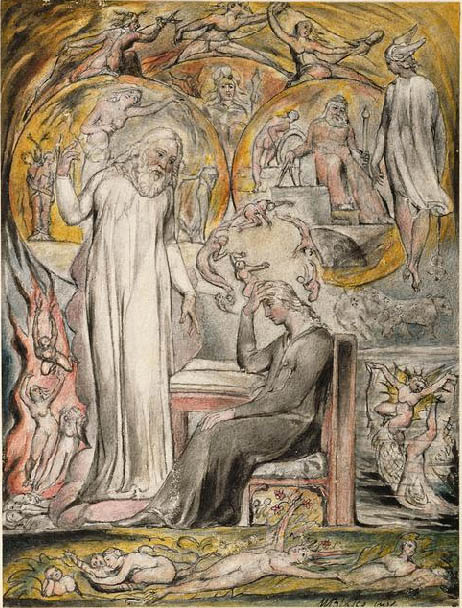

Last year’s ‘Frye Symposium’ roundtable was on the topic “How Might The Educated Imagination lead us forth into the 21st Century.” Panelists included Jean Wilson, Germaine Warkentin, Serge-Patrice Thibodeau (award-winning Acadian poet and publisher), and Serge Morin (retired philosophy professor who invited Frye to Moncton in the fall of 1990, to give the Pascal Poirier Lecture at L’Université de Moncton). I’ve already posted a copy of Germaine Warkentin’s opening remarks at this roundtable, and I hope to post Serge’s remarks, once I get a better copy. The topic for this year’s symposium roundtable is “Voyaging into the Unknown in Folk Tales and in Dreams” which I think has many Frygian ramifications, not least the life-long obsession with the downward spiral, the cave, the labyrinth, katabasis, etc. Three of the panellists (André Lemelin from Quebec, Kay Stone from Winnipeg, and Ronald Labelle from Moncton) are experts in storytelling and folklore, invited to the festival for a special storytelling event. The 4th panellist, Craig Stephenson, is a Jungian analyst invited to the festival to give a talk on Jung and Frye.

Any suggestions for improving, changing, revamping any of these 2010 roundtable titles and topics would be welcome, these next few weeks. A press conference to announce the authors and draft program for 2010 is scheduled for next Tuesday, February 16. We hope there will be big Fryes and small Fryes in the audience come April, especially at the lectures and roundtables, and that you will have questions that come straight out of Frye. Perhaps, if you can’t attend, you might pose a question that one of us here could ask.

You can register here.