Trevor Losh-Johnson in an email points out that Salinger “teaches us all not to be phonies.” Good enough.

The Demonic and Desire

Responding to Michael Happy’s post

I am glad you posted on demonic modulation, Michael, because I think demonic parody is integral to Frye’s conception of Romance, which itself seems integral to his view of literature in relation to primary concerns.

It may be useful to consider demonic modulation in terms the Anatomy’s description of demonic imagery and parody. The apocalyptic world, Frye writes, “present, in the first place, the categories of reality in the forms of human desire, as indicated by the forms they assume under the work of human civilization.” Demonic imagery embodies what desire rejects, and “one of the central themes of demonic imagery is parody, the mocking of the exuberant play of art by suggesting its imitation in terms of ‘real life.’”. In The Secular Scripture he points out that, as the conventions of myth and Romance become gradually displaced into “realist” modes, there is also a parallel gradation of parody serving to assimilate those conventions.

This might provide for an alliance between demonic modulation, which relates to the inversion of customary associations, and the Promethean Furnace in Words with Power. “The world of titans,” Frye writes, “has usually been regarded as simply evil, and the word ‘demonic’ is normally used… to mean a death-centered parody of human life.” (pg. 276). However, “Prometheus is the patron of the attitude, which has sporadically appeared in literature ever since Lucretius, of ignoring the gods on the ground that even if they exist they can only be alien beings unconcerned with human life.” (pg. 277). In this modulation, what would customarily be associated with the demonic is in fact an affirmation of life through desire, over a world that more closely resembles our own.

That is to say that there comes a point when what is displaced in the text, because it is repressed by the ascendant moral values it flaunts, becomes in fact a life affirming principle. Prometheus becomes Christ-like, the demonic becomes apocalyptic. This may inform the simple and more humane Robin Hood motifs that run through Literature, and our experience, from Huckleberry Finn protecting Jim from the slave “masters”, to what makes it obscene for certain ideologies to speak against aid for suffering countries. And it is why, for example, the homophobic (and perhaps homicidal) work of Christian evangelicals in Uganda has been so repellent a parody of the Christian exhortation to good works.

More from Frye on Relevance

Herbert Marcuse

Frye on Zweckwissenschaft:

One main theme of Part Three is: the N-S axis of concern is revolutionary, & the W-E one is liberal, not speculative, but simply broadening & enlarging. Revolutionary characteristics are: the enforced loyalty of a minority group (Jews, early Christians); belief in a unique historical revelation; resistance to “revisionism”; establishment of a rigorous canon of myth; rejection of knowledge for its own sake (demand for relevance or Zweckwissenschaft). Judaism was the only revolutionary monotheism produced in the ancient world, and Christianity inherited the characteristics that made Tacitus scream & Marcus Aurelius talk about their parataxis [sheer obstinacy].

(The “Third Book” Notebooks, Notebook 12, par. 304)

A certain amount of contemporary agitation seems to be beating the track of the “think with your blood” exhortations of the Nazis a generation ago, for whom also “relevance” (Zweckwissenschaft, u.s.w.) was a constant watchword. Such agitation aims, consciously or unconsciously, at a closed myth of concern, which is thought of as already containing all the essential answers, at least potentially, so that it contains the power of veto over scholarship and imagination. Marcuse’s notion of “repressive tolerance,” that concerned issues have a right and a wrong side, and that those who are simply right need not bother tolerating those who are merely wrong, is typical of the kind of hysteria that an age like ours throws up. That age is so precariously balanced, however, that a closed myth can only maintain a static tyranny until it is blown to pieces, either externally in war or internally through the explosion of what it tries to suppress.

(The Critical Path, 155)

Demonic Modulation

The Educated Imagination was the first book by Frye I read, and it’s therefore always a touchstone for me. You never forget your first love. Meanwhile, Fearful Symmetry remains Frye’s most mind-blowing text, The Great Code his most challenging, and Words With Power his most expansive for practical critical purposes. But like many Frygians, I’m guessing, I regularly return to Anatomy of Criticism, and, it seems, almost involuntarily. Every once in awhile I find myself preoccupied by something from it that I seem to recall out of the blue. Thanks to an email exchange with Peter Yan and the cumulative effect of posts over the last week or so, I have been pondering an issue Frye briefly raises in Anatomy that gets relatively little attention (the exception perhaps being Bob Denham’s Northrop Frye and Critical Method): “demonic modulation.”

With demonic modulation Frye makes a much needed distinction between “the moral” and “the desirable”:

The moral and the desirable have many important and significant connections, but still morality, which comes to terms with experience and necessity, is one thing, and desire, which tries to escape from necessity, is quite another. Thus literature is as a rule less inflexible than morality, and it owes much of its status as a liberal art to that fact. The qualities that religion and morality call ribald, obscene, subversive, lewd and blasphemous have an essential place in literature but often they can achieve expression only through ingenious techniques of displacement. (AC 156)

How does demonic modulation manage this? By way of “the deliberate reversal of the customary moral associations of archetypes.” For example, in literature, whatever the current status of received moral standards,

a free and equal society may be symbolized by a band of robbers, pirates, or gypsies; or true love may be symbolized by the triumph of an adulterous liaison over marriage, as in most triangle comedy; by a homosexual passion (if it is true love that is celebrated in Virgil’s second eclogue) or an incestuous one, as in many Romantics. (AC 156-7)

A.C. Hamilton in Northrop Frye: Anatomy of his Criticism describes Anatomy, published in 1957, as very much a book of its time — so Frye’s reference to various forms of forbidden love as “modulations” must have been eyebrow-raising for many conventionally-minded readers. Frye does not call it that here, but what he is clearly talking about is literature’s unique ability to express primary concerns beyond the pervasive gravitational pull of secondary ones.

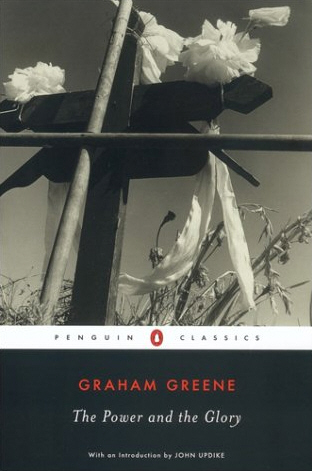

I’m pretty sure I can remember the first time I ever became aware of this in my own reading experience: Graham Green’s The Power and the Glory, which was an assigned text back when I was in the 11th grade. I remember struggling with the contradiction between Greene’s “whiskey priest”‘s all too human frailty and his compelling nature as a human being I felt I could love and identify with, despite his obvious failings. I’m also pretty sure that even though I wondered about it at the time, I was nevertheless grateful to accept that it was so. Literature was showing me something I otherwise couldn’t account for with any certainty; and within a year I read The Educated Imagination for the first time which articulated what I in some sense already knew but simply could not yet say.

Literature references ideology but does not promote it. Literature gives expression to primary concerns, most especially when they are contrary to the ideologies that readily suppress them. Desire may on occasion be moral, but the moral can never contain desire — and in the struggle between the moral as a secondary concern and desire as a primary one, desire always prevails. That, paraphrasing Wilde’s Lady Bracknell, is what fiction means.

“Something threatening about Frye”

Glen R. Gill’s Northrop Frye and the Phenomenology of Myth

Responding to Merv Nicholson’s post

The recent posts recalling the death of Northrop Frye have been incredibly interesting to read, especially from the position of someone who was seven when Frye died.

Indeed, there is, as Merv suggests, something “threatening about Frye.” I was trained in theory –“high theory”– and was frustrated. One professor suggested I read Anatomy of Criticism; I read it and was convinced. I haven’t looked back. Frye is a powerful thinker and one who forces us to think deeply and critically about literature in and of itself and then allows us to move outward from it. So much of the current academy is concerned with the “extra-literary,” as Wellek might call it. In some regards, Frye says: yes, you can have it both ways. But Frye demands that if we dp have it “both ways,” that it be done well. Frye masterfully treats literature as literature, but also always seems to be able to relate it to the “real” world.

I am still not certain about Frye and Bloom. I don’t think that Bloom ever usurped or replaced Frye (despite many attempts); likewise, Frye was certainly quite critical of Bloom’s project. The Anxiety of Influence and A Map of Misreading are perhaps the greatest attempts to distance and displace Frye, but, in the attempt they actually begin to reconfirm Frye’s importance. The same can be said, I think, of Fredric Jameson’s The Political Unconscious. In some ways, I wonder if Frye is “dead” when he has arguably influenced some of the most important theorists currently writing; the two mentioned above, for instance (I also think of Tzvetan Todorov and Roland Barthes here), but also someone like Emily Apter who delivered two astounding lectures as Northrop Frye Professor of Literary Theory at the Centre for Comparative Literature. These lectures were not direct dialogues with Frye, but they were certainly, I would argue, (polemical) engagements with Frye. It would seem that there is a “new generation,” although perhaps a quiet generation right now. But there have been some loud cries; for example, Northrop Frye and the Phenomenology of Myth (2006) by Glen Robert Gill which is, without doubt, an impressive reading of Frye.

Zweckwissenschaft

Responding to Peter Yan’s comment in Russell Perkin’s earlier post

Yes, Frye cites the Nazi term Zweckwissenschaft, which means target-knowledge; the Nazis may have invented it, but it is a term very relevant to what has been going on in universities for some time now.

For example, in my faculty we are constantly reminded that the best way to get funding is to link your research in some way to the “purposive” areas of research in the university, such as areas of medical research, neuro-science, business. So we end up, for example, with funding in our faculty for a program in music and neuro-science. This is one reason, I think, for the success of cultural studies: it is a discipline that applies tenets of existing social sciences such as sociology to the contemporary cultural scene and thus it presents itself in a very direct and obvious way as socially “relevant.” In addition, courses on popular media, music, and visual culture fill the seats. You may not be as relevant as the medical and business schools, but you can be forgiven if you draw in students.

The seductiveness of relevance also explains the allure of evo-criticism, neuro-criticism, cognitive criticism: the more scientific you are the more relevant you can claim to be. This is not of course in any way what Frye meant by making literary criticism scientific. It is, in fact, a flagrant instance of what he inveighed against in Anatomy, the turning of literary criticism to other disciplines for its authority.

Literary scholars feel the pressure to prove their usefulness, and, unfortunately, the strong argument that Frye makes about the inherently prophetic and counter-cultural authority of literature and the arts in society–the social context of literary criticism he discusses in The Critical Path–is not what most university administrators have in mind. They are, as their institutions dictate, mostly “pigs,” in ) Rohan Maitzen’s (and Mill’s) sense of the word.

Relgious Knowledge, Lecture 16

Macbeth, First Folio, 1623

Lecture 16. February 3, 1948

ELEMENTS OF TRAGEDY

Aristotle’s catharsis means that the audience is not to have pity or fear. The correct response is: the hero is a man suffering from the tragic flaw; how very like things are. The Greek idea of fate was not external; it is the way things always happen. The law of human life is not moral, but a law nevertheless.

Tragedy is a kind of implicit comedy. It is the full statement of which comedy gives only a part. The complete story of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion is a comedy. The implicit resurrection gives balance and serenity. Tragedy completes itself as comedy. The story of Christ has no ultimate tragedy. Death is a tragedy, but there is resurrection here.

In other tragedies the hero dies on stage and he revives in the mind of the audience. Tragedy is the development of the ritual of sacrifice. The typical act is the death of the central figure, the king or prince in whose death the people find life. Aristotle’s catharsis is not a moral quality. It casts out pity and fear, which are moral good and moral evil.

To say that Macbeth is a bad man is the reaction of terror, of moral evil. Sympathy with him on the grounds of fate, his wife’s influence, etc., is pity: moral sympathy with the hero. The real function of tragedy gets beyond moral reaction. The point is not whether Macbeth was good or bad. Tragedy goes beyond that. The catharsis in the audience is that the dead man on the stage is alive in them. The audience is united in the death of the hero. Modern tragedies are moral in that they stimulate sympathy or condemnation. Shaw’s St. Joan is moral. In King Lear, though, his death is a release. He attempted to find divinity in his kingship and failed. He found it in suffering humanity.

From the spectator’s point of view, Job is funny. The watcher is released from the action and his perspective, therefore, is one of comedy. Tragedy has the reversal of perspective. Tragedy is a work of art seen from the spectator’s point of view as entertainment. Hamlet asks to be written up: Othello, the same. Tragedy has a point when limited in art form and seen by an audience.

The audience’s perspective is comic because they are the watchers. The tragic hero is unaware of the humiliation of being watched. Lear is mercifully unaware of this when scampering around the stage mad. Hamlet feels that all eyes are upon him. He feels this to such a point that he takes it out on Ophelia. He kills Polonius because he is being watched. In Aeschylus’ Prometheus, he is stretched out on a rock. He speaks first so that people won’t stare at him. He says, “Behold the spectacle.”

Job sees God as an inscrutable watcher. In Chapter 7. he describes his fallen state––no sense in what happens––if there is a God who doesn’t interfere, then he is merely the watcher, and this is unbearable to Job. Verse 11: “Am I a sea or a whale that thou settest a watch over me?” Verse 8: “The eye of him that hath seen me shall see me no more; thine eyes are upon me and I am not.” A sense of loneliness, but of being watched.

Othello’s black skin means that all eyes are drawn to him. Here, it is subtler. The comforters are not making fun of Job. But sympathy is harder to put up with then ridicule. Job knows God acts — but why this way? It worries Job.

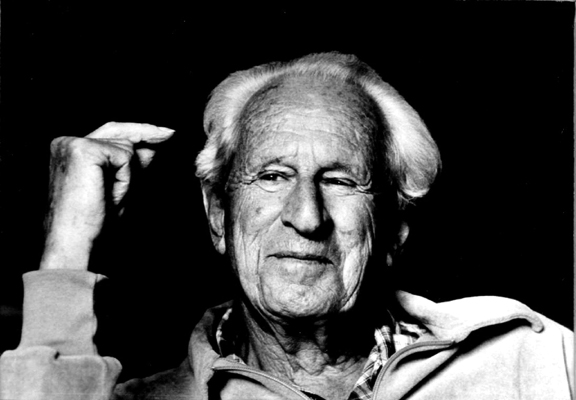

Bob Rodgers: Getting to Know Northrop Frye

Bob Rodgers is a documentary filmmaker, TV producer, and writer, currently developing a web-based series titled “The Bible and Literature with Northrop Frye.”

I am fresh from the West when I join Northrop Frye’s graduate class at the University of Toronto in 1959. I know his reputation: Fearful Symmetry is twelve years old, Anatomy of Criticism barely two. Frye is already approaching canonization in the world of literary criticism and celebrity status at the University of Toronto. What comes as a shock is his appearance. He enters the room so unobtrusively it is as though he simply materializes from behind the podium, one eye eagle sharp as it surveys the room, the other with a slightly drooping eyelid as if out of shyness. Or is it irony? Setting Blake’s Collected Works, his only prop, on the podium and gazing at us through glasses that seem to be the wrong prescription, he falls short of the glamorous figure I had anticipated.

Then moments after he begins speaking I forget where I am. I am hearing things as if in a foreign language, yet I seem to understand. As one startling idea follows another I am dazzled by the reach of his mind. At the end of class I haltingly approach him and am granted an interview to discuss my proposal for a term paper. I’m nervous. It is one thing to sit in the relative anonymity of a classroom, quite another to sit across from him face to face.

The doorway between the marble hallway and the hardwood floor of his office in old Emmanuel College has a slightly raised sill I fail to notice. I catch my toe on it and trip. In an effort to regain my balance, I lunge forward, stopping just before crashing into his desk. He looks up in alarm, rising half from his chair as if to fend off a tackle. It is an unpropitious beginning for my proposed topic: William Blake and the Dynamics of Energy and Order.

The imposing yet aloof man I met that day (once he settled back in his chair) was nothing like the man I am coming to know all these years later as I read away at U of T Press’s mammoth publishing enterprise, The Collected Works of Northrop Frye. I am especially interested in the diaries and letters and notebooks that bring out his personal side, and not just one side but many—the self-confessed physical coward, the self-confessed genius, the frustrated novelist and unfulfilled composer, the reluctant introvert and what many would call the dangerous heretic. Most of all I was surprised by his liberal use of what he playfully called dirty words, which would have shocked his orthodox Methodist family and no doubt did shock some of his Victoria College contemporaries. I remember when I was young feeling the same surprise when I learned that Roosevelt had a mistress.

The published works seem certain to establish Frye’s reputation as one of the Twentieth Century’s greatest humanists. The voice is distinctive but impersonal. Only in the previously unpublished writing do we come into contact with the inner man, by way of an unceasing self evaluation in which nothing personal is censored. How many writers would hazard a remark like this that so notoriously troubled Harold Bloom:

Statement for the Day of my Death. The twentieth century saw an amazing development of scholarship and criticism in the humanities, carried out by people who were more intelligent, better trained, had more languages, had a better sense of proportion, and were infinitely more accurate scholars and professional men than I. I had genius. No one else in the field known to me had quite that.

Could these be the words of a braggart? Given what I remember as a student and what I’m learning of the man today as I go through the notebooks, all I can do is applaud him for acknowledging his gift and having the courage to declare it. Nietzsche was right. It is impossible to be a genius and not know it.

New Generation of Critics vs. the Philistines

Responding to Merv Nicholson’s earlier post

Merv, from my secondary school vantage point, you can rest assured there is a new generation of Frye critics. The Educated Imagination is being taught in more high schools than ever; not only by DeepFrye’s like myself, but students. In one school a student ON HER OWN ACCORD read EI and then pushed for a presentation before the school’s English department to have all the teachers teach Frye. Like the classics, Frye’s work refuses to go away — no matter what the School of Resentment says.

If Frye is dead, refuted, parodied, caricatured, it is merely the myth of Goliath: new Professor Davids making a reputation slinging (mostly dirt) at the Goliath Frye. But they are the true Philistines. If you caught the exchanges between David Richter and others on this site, you will see what I mean.

I do teach my Grade 12 students other schools of critical thought, but Frye gives them the most freedom to be creative. Their essays are mostly bereft of secondary sources, as they engage the text directly, doing their own archetype spotting, not to mention ideologue spotting too. (I mean, how will a Marxist criticism of say Oedipus Rex go???)

What is most intimidating of Frye’s technique in the academy is that it exposes the gatekeepers for what they are: power hungry ideologues smashing whatever is in their way, including literature and literary criticism. In fact, Frye’s latest taxonomy of modes in Words with Power (descriptive, dialectical, ideologial, mythical, metaliteray) can also be used to chart all the schools of criticism, most of which fall under “dialectical/ideological”.

Mervyn Nicholson: On the Death of Northrop Frye

I remember where I was when Norrie died. My wife cried out something or other, and told me she had just heard on the CBC the news, that “Northrop Frye is dead.” It was definitely a shock. He was, I was going to say, so young. By today’s standards, he wasn’t that old. But he was gone, and that wonderful voice of wisdom and of unparalleled scholarship was gone, too. The conference planned to celebrate his 80th birthday became a conference of retrospection on his career.

But Northrop Frye had already been dead for some time.

Not dead physically, of course, but dead in terms of his reputation, in terms of influence, in terms of his place in the intellectual world. And nowhere was his reputation more collapsed than in the country of his birth and that earlier had been proud to claim him as his own, Canada.

Frye, as Bob Denham has reminded us, was for a time one of the most cited thinkers. For a period he had remarkable influence in the academy—and not just in the academy, but in society more generally, especially Canadian society. After all, nobody had more influence on the formation of Canadian literature as a discipline, and Canadian studies more generally, than he did. He was a “public intellectual,” consulted by the Trudeau government, appearing on television, even consulted in the development of Expo 67 in Montreal. But Frye’s influence vanished astonishingly rapidly.

Outside of Blake studies, his influence was intense but brief, beginning more or less with the publication of Anatomy of Criticism, and abruptly ending in the mid 70s in the centres of academic power, where it counts. Bloom’s A Map of Misreading, basically a repudiation of Frye, is the indicator that the academic establishment would no longer tolerate Northrop Frye. He was out. Derrida was in.

Viewed more closely, Frye was always more popular with students than with academics. For academics, there was always something uncomfortable and even unacceptable about Frye, and that explains, in part, why his reputation dwindled and disappeared as rapidly as it did. Now, if you cite Frye favourably in a conference paper or an article or in some other academic setting, the likely reaction of your audience will be disbelief, if not open ridicule. Canadianists have long since repudiated his ideas about Canada, and the once-famous Conclusion to a Literary History of Canada is now treated as colonialist bric-a-brac. I hope I am exaggerating.

Yes, Frye is dead, in more than one sense. True, there is a group of what Professor Denham calls “keepers of the flame,” but apart from a rather small (older) group, interest is feeble.

Last spring, at Carleton University, I met with Joseph Adamson and Michael Happy at the annual Social Sciences / Humanities Congress. We wanted to find a way to stimulate interest in Frye, to bring back a focus on his work that would actually do justice to this vital thinker. For years I’ve been wanting to start a journal on Frye-related concerns. I wanted to get young people interested in Frye—really, to acquaint a new generation with this powerful and interesting thinker. I wondered if a society should be formed. Joe and Michael had similar ideas and wishes, and Michael had the brilliant idea of starting a blog, which you see here, and which has thrived mightily under the direction of Michael and Joe.

What I wanted, and what I believe they wanted, too, was not just a memorializing-biographical-bibliographical approach to Frye, but a forum which would stimulate interest in the sort of ideas that Frye worked with, that would develop and apply, and explicate in a fair and creative way, what Frye did, what Frye thought. Frye has been so misrepresented, so caricatured and distorted, that the actual content of his ideas has rarely been discussed or given a real hearing. In my own work, as his last Ph.D. student, I have always intended to follow his lead in developing the sort of ideas he pioneered, and my books Male Envy and 13 Ways of Looking at Images, though superficially very different from Frye, are yet, in my view, in the direct line of his thought.

To me, the extraordinary defacement of Frye’s thought is in itself a subject of deep interest. Why is Frye not accorded the proper attention that a thinker of his depth and originality deserves? I have always believed that there is something actually threatening about Frye, especially in the academy.

I wonder if others share this view. And I wonder what we can do about it. Bring on the new generation!