This engaging discussion has led Joe––in his third answer to what for Frye is the function of literature in society––to what I see as the punch line in Frye, the notion of expanded consciousness that comes from vision. Frye has a compelling account of this and other matters in his essay, “Literary and Linguistic Scholarship in a Postliterate World,” where he says, after giving his familiar example of metaphorical identification in the Palaeolithic cave drawings, “Later we find the metaphorical imagination expanding into the worlds of dream, belief, vision, fantasy, ideas, as well as human society and nature, and annexing them all to the enlarging consciousness” (“The Secular Scripture” and Other Writings on Critical Theory, CW 18, 294). [This comes from the volume Joe and Jean Wilson edited, which is, I think, the richest collection of Frye’s essays on critical theory.]

In the 1970s Frye often wrote about what he called the four levels of awareness, but “awareness” as a category tends to disappear from the writings in the last decade of his life, having been replaced by “consciousness.” This word is often modified by “enlarged,” “expanded,” and “intensified.” The cave drawings at Lascaux, Altamira, and elsewhere are an example of what Lévy-Bruhl called participation mystique, the imaginative identification with things, including other people, outside the self, or an absorption of one’s consciousness with the natural world into an undifferentiated state of archaic identity. In such a process of metaphorical identification the subject and object merge into one, but the sense of identity is existential rather than verbal (See Words with Power, 250, and Northrop Frye’s Late Notebooks, 2:503).

But what does the “intensity or expansion of consciousness” entail for Frye? This is a somewhat slippery phrase to get hold of because Frye reflects on the implications of the phrase only obliquely. But several years ago I nevertheless tried to set down some of the chief features of “expanded consciousness.” It came out like this:

1. It is a function of kerygma. Ordinary rhetoric “seldom comes near the primary concern of ‘How do I live a more abundant life?’ This latter on the other hand is the central theme of all genuine kerygmatic, whether we find it in the Sermon on the Mount, the Deer Park Sermon of Buddha, the Koran, or in a secular book that revolutionizes our consciousness. In poetry anything can be juxtaposed, or implicitly identified with, anything else. Kerygma takes this a step further and says: ‘you are what you identify with.’ We are close to the kerygmatic whenever we meet the statement, as we do surprisingly often in contemporary writing, that it seems to be language that uses man rather than man that uses language” (Words with Power, 116).

2. It does not necessarily signify religion or a religious experience, but it can be “the precondition for any ecumenical or everlasting-gospel religion” (Late Notebooks, 1:17).

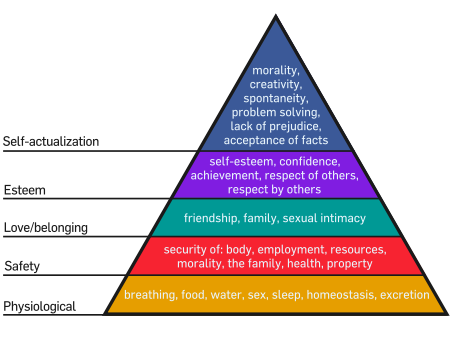

3. Whatever the techniques used to expand consciousness (for example, yoga, Zen, psychosynthesis, meditation, drugs), or whatever forms it takes (for example, dreams, fantasies, the “peak experiences” described by Maslow, ecstatic music), the language of such consciousness always turns out to be metaphorical. Thus literature is the guide to higher consciousness, just as Virgil was Dante’s guide to the expanded vision represented by Beatrice (Late Notebooks, 2:717; Words with Power, 28–9). Still, Frye believes that language is the primary means of “intensifying consciousness, lifting us into a new dimension of being altogether” (LN, 2:717).

4. “Vision” is the word that best fits the heightened awareness that comes with the imagination’s opening of the doors of perception. What the subject sees may be “only an elusive and vanishing glimpse. Glimpse of what? To try to answer this question is to remove it to a different category of experience. If we knew what it was, it would be an object perceived in time and space. And it is not an object, but something uniting the objective with ourselves” (Words with Power, 83).

5. The principle behind the epiphanic experience that permits things to be seen with a special luminousness is that “things are not fully seen until they become hallucinatory. Not actual hallucinations, because those would merely substitute subjective for objective visions, but objective things transfigured by identification with the perceiver. An object impregnated, so to speak, by a perceiver is transformed into a presence” (Words with Power, 88).

6. Intense consciousness does not sever one from the body or the physical roots of experience. “The word spiritual in English may have a rather hollow and booming sound to some: it is often detached from the spiritual body and made to mean an empty shadow of the material, as with churches who offer us spiritual food that we cannot eat and spiritual riches that we cannot spend. Here spirit is being confused with soul, which traditionally fights with and contradicts the body, instead of extending bodily experience into another dimension. The Song of Songs . . . is a spiritual song of love: it expresses erotic feeling on all levels of consciousness, but does not run away from its physical basis or cut off its physical roots. We have to think of such phrases as ‘a spirited performance’ to realize that spirit can refer to ordinary consciousness at its most intense: the gaya scienza, or mental life as play. . . . Similar overtones are in the words esprit and Geist” (Words with Power, 128). Or again, St. John of the Cross makes “a modulation from existential sex metaphor (M2) to existential expanding of consciousness metaphor (M1)” (Late Notebooks, 120). As in Aufhebung, things lifted to another level do not cancel their connection to the previous level: “M2” is still present at the higher level. Chapter 6 (“The Garden”) of Words with Power “is concerned partly, if not mainly, with getting over the either-or antithesis between the spiritual and the physical, Agape love and Eros love” (Late Notebooks, 2:451). Again, “spiritual love expands from the erotic and does not run away from it” (Words with Power, 224).

7. Intensified consciousness is represented by images of both ascent and descent: “images of ascent are connected with the intensifying of consciousness, and images of descent with the reinforcing of it by other forms of awareness, such as fantasy or dream. The most common images of ascent are ladders, mountains, towers, and trees; of descent, caves or dives into water” (Words with Power, 151). These images, which arrange themselves along the axis mundi, are revealed with exceptional insight in some of Frye’s most powerfully perceptive writing, the last four chapters of Words with Power. In these concentrated chapters Frye illustrates how four central archetypes connect the ordinary world to the world of higher consciousness: the mountain and the cave emphasizing wisdom and the word, and the garden and the furnace emphasizing love and the spirit.

8. Expanded consciousness is both individual and social.

9. The raising of consciousness is revelation (Late Notebooks, 1:61).