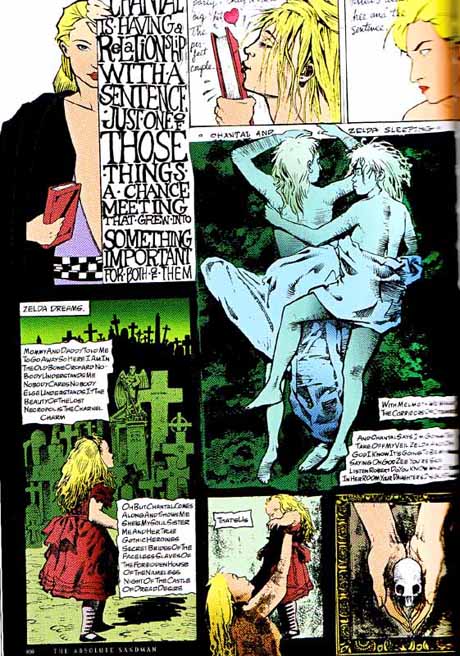

Illustration from a Dutch edition of Justine, or the Misfortunes of Virtue

Further to yesterday’s post, here is a collection of Frye references to de Sade.

It is an elementary axiom in criticism that morally the lion lies down with the lamb. Bunyan and Rochester, Sade and Jane Austen, The Miller’s Tale and The Second Nun’s Tale, are all equally elements of a liberal education, and the only moral criterion to be applied to them is that of decorum. Similarly, the moral attitude taken by the poet in his work derives largely from the structure of that work. Thus the fact that Le Malade Imaginaire is a comedy is the only reason for making Argan’s wife a hypocrite—she must be got rid of to make the play end happily (Anatomy of Criticism, CW 22, 105-6)

Blake says that we live in, if you like, a fallen world, that is, a world of great inequities, of privilege, a world of ferocity. He doesn’t have an idealized view of nature like Rousseau. He doesn’t believe in the noble savage. Wordsworth says that nature is our teacher, and the Marquis de Sade says that nature justifies your pleasure in inflicting pain on others. Blake would say that there is a lot more evidence for the Marquis de Sade’s view of nature than for Wordsworth’s. So for Blake what happens is that the child, who is the central figure of the Songs of Innocence, is born believing that the world is made for his benefit, that the world makes human sense. He then grows up and discovers that the world isn’t like this at all. So what happens to his childlike vision? Blake says it gets driven underground, what we would now call the subconscious. There you have the embryonic mythical shape that is worked on later by people like Schopenhauer, Marx, and Freud. (Cayley interview, CW 24, 958)

It is unfortunate that Praz’s influential book concentrates so much on the purely psychological elements of sadism, for sadism is far more important as a sardonic parody of the Rousseauist view of society. According to de Sade, nature teaches us that the greatest good of life is pleasure, and there is no keener pleasure than the inflicting (or, for masochists, who complete the theory, the suffering) of pain. A society of sadistic masters and masochistic slaves would therefore be a “natural” society. There is no evidence that Rousseau’s natural society ever did, could, or will exist: the evidence that it is natural for man to form societies that condemn the majority to misery and humiliation and give a small group the privilege of enjoying their torments is afforded by the whole of human history. The sense that ecstasy and pain are really the same thing is connected with the fact, just mentioned, that for Romantic mythology the greatest experiences of life originate in a world which is also the world of death and destruction. (A Study of English Romanticism, CW 17, 121-2)

The symbol of the artist as criminal, however, goes much deeper. I spoke of the way in which optimistic theories of progress and revolution had grown out of Rousseau’s conception of a society of nature and reason buried under the injustices of civilization and awaiting release. But, around the same time, the Marquis de Sade was expounding a very different view of the natural society. According to this, nature teaches us that pleasure is the highest good in life, and the keenest form of pleasure consists in inflicting or suffering pain. Hence the real natural society would not be the reign of equality and reason prophesied by Rousseau: it would be a society in which those who liked tormenting others were set free to do so. So far as evidence is relevant, there is more evidence for de Sade’s theory of natural society than there is for Rousseau’s. (The Modern Century, CW 11, 46-7)

I’ve said too that de Sade is just as right about “nature” as Wordsworth is: he simply points to its predatory & parasitic side. But no animal acts with the malice that man does: that’s a product of consciousness. (Late Notebooks, CW 5, 56)

Continue reading →